不吸烟者和吸烟者的肺磨玻璃结节:临床和基因特征

简介

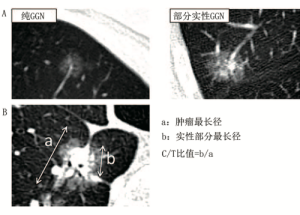

计算机断层扫描(CT)上的肺磨玻璃结节(GGN)是一种模糊的病变,不会遮盖支气管或肺血管的影像学结构。良恶性病变均有可能表现为GGN,例如,局灶性间质纤维化、炎症或出血[1]。但是缓慢生长或稳定的GGN往往是早期肺癌或浸润前病变:非典型腺瘤样增生(atypical adenomatous hyperplasia,AAH)或原位腺癌(adenocarcinoma in situ,AIS)。AAH、AIS和鳞屑成分为主肺腺癌沿着肺泡结构生长[2],能够维持含气空间。因此,这些病变在CT上表现为GGN。GGN分为纯GGN和兼具磨玻璃和实性成分的部分实性GGN(图1A)。

我们之前回顾了GGN的病理特征和自然发展史[3],GGN实性成分的比例与病理性侵袭性病变密切相关。GGN实性成分最长直径/GGN最长直径(C/T,固结比)通常用于评估磨玻璃成分的比例(图1B)。根据经验,C/T值≤0.5已被建议作为病理浸润性的基准,因为直径≤3cm的GGN中C/T值>0.5的淋巴结转移的发生率在21%~26%[4-6]。在显微镜下分析可以看到,CT上GGN的实性成分通常包含病理浸润性部分。通常AAH和AIS在CT表现为纯GGN,而微浸润性腺癌(minimally invasive adenocarcinoma,MIA)和鳞屑样腺癌表现为部分实性GGN。其中有一些GGN表现出逐渐增长,但其他GGN多年来保持不变。

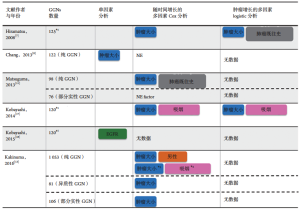

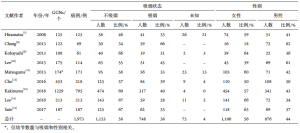

我们收集了最近的研究报告,根据吸烟史分析了100多个GGN患者[7-15](表1)。总共有大约60%的GGN患者存在于从不吸烟者中。虽然吸烟状况的发生率存在一些不一致,但9篇文章中有8篇报道GGN在不吸烟者中更常被发现。因此,GGN可被视为从不吸烟者的肺癌特征之一。在这篇综述中,我们更新了GGN在吸烟和遗传改变方面的最新数据,以深入了解肺癌进展的生物学特征,并提出GGN临床管理策略。

Full table

随访期的GGN患者

尽管GGN经常在没有增长的情况下保持稳定多年,但在我们最近的回顾中总结了4份研究报告,大约20%的纯GGN和40%的部分实性GGN会逐渐增长,或实性成分增加[3],我们建议3年的随访期是基于GGN体积倍增时间来区分这些病变的一个合理基准[9]。2016年,Kakinuma等报道了日本的一个前瞻性多中心研究结果[13],共评估了795名患者,共1 229个GGN,平均随访4.3年。除了纯GGN和部分固体GGN外,作者还提出异质性GGN,定义为仅在肺窗中具有实性成分但不在纵隔窗显示的GGN。对于纯的、异质性的和部分实性GGN,随访5年时的2 mm生长概率分别为14%、24%和48%,这些数据类似于我们文章[3]中的结果。然而值得注意的是,即使在3年的随访后,一些GGN也开始增长。根据这些前瞻性数据,2017年更新的Fleischner Society指南中的最短随访期从3年延长至5年[16]。

GGN增长的预测因子

此前报道的预测因子和统计问题

如果我们能够预测哪些GGN会增长、哪些GGN保持稳定是很有意义的,虽然有报道显示病变直径和肺癌的既往史是GGN生长的预测因子[7-8,11](图2),但对GGN增长的统计分析依然受到两个主要问题的影响。首先,一些患者同时具有多个GGN,当所有GGN被独立计数时,患者的一些因素(例如,性别或吸烟状况)会被重复计算;其次,将“无增长”定义为结果是困难的,因为在特定时期内没有增长的GGN可能会在此之后开始增长。

吸烟对GGN生长的影响

考虑到上述问题,我们进行了两次独立分析[17]。首先,评估每个病变的“2 mm生长时间”,并使用Cox比例风险模型进行单变量和多变量分析。为了避免在多个病变的情况下可能存在偏差,我们仅针对每位患者的最大病变进行了亚组分析。然后将“2 mm生长的发生率”定义为结果,并且使用逻辑回归模型进行单变量和多变量分析。为严格定义“无生长”,我们根据之前的研究[9]排除了观察时间<3年的病变。基于这些分析结果,我们发现除了GGN直径较大外,吸烟也是一种新的生长预测因子[17](图2)。

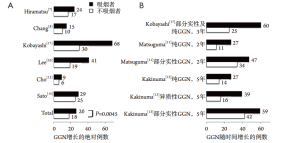

考虑到GGNs更常见于不吸烟者,吸烟史作为增长的预测因素似乎是矛盾的。我们收集了最近关于吸烟状况和GGN增长的研究[7-8,10,12,15,17](图3)。来自6篇文章的综合数据显示,基于“增长”或“无增长”数据的GGN增长频率在吸烟者中明显高于不吸烟者(26% vs 18%,P=0.0045)。在这6篇文章中,3篇报道了“生长时间”的数据[11,13,17],在2、3或5年内GGN生长的频率(图3)。所有数据均表明吸烟者的GGN比不吸烟者更容易生长。值得注意的是,一项前瞻性多机构研究还报道,通过多变量分析,除了病变大小和男性外,病变大小和吸烟史也是实性成分“2 mm增长”的预测因子[13]。在我们之前的分析中,男性和吸烟密切相关[17]。虽然目前尚不清楚GGN诊断后戒烟是否会改变这些GGN的临床表现,但在这种情况下也应该强调戒烟。

还有一篇关于吸烟对GGN影像学表现影响的有趣报道。Remy-Jardin等研究了在平均5.5年的时间内,连续接受CT检查的111名受试者结节的生长变化。在吸烟者的初始评估中,有28%检测到GGN,最终评估时这一比例上升到42%(P=0.02),然而在不吸烟者中这一比例却没有发生显著变化[19]。这些数据表明,由于长期接触吸烟,可能会新出现一部分GGN。

吸烟可以使体细胞中癌症相关基因突变,并诱导DNA损伤导致癌症。Alexandrov等收集了来自癌症基因组图谱(the Cancer Genome Atlas,TCGA)、国际癌症基因组协会(International Cancer Genome Consortium,ICGC)的5 243种癌症的体细胞突变数据,以及其他17篇文章,揭示了突变特征与吸烟之间的关联[20]。分析显示,碱基替代突变的总数与吸烟年数正相关。对于肺腺癌,作者估计每组基因累积约150个基因突变[20]。考虑到这些数据,由吸烟引起的累积突变可能诱导GGN生长。

基因突变与GGN生长之间的关联

EGFR突变

如上所述,既往研究表明,病变直径和吸烟(或男性)是GGN生长的预测因子[13,17]。然而,生长或没有生长的GGN之间的遗传差异仍不清楚。

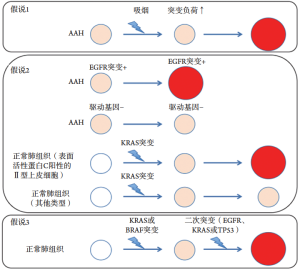

因此,我们对手术切除的GGN进行了遗传分析[18]。在104个GGN中评估EGFR、KRAS、ALK和HER2的基因突变,并且由于驱动基因之间的相互排斥关系,所有病变分类为EGFR-阳性、KRAS-阳性、ALK-阳性、HER2-阳性或四重阴性组。EGFR、KRAS、ALK和HER2突变的频率分别为64%、4%、3%和4%。据我们所知,这是唯一一项分析GGN遗传改变与其生长之间关系的研究。我们的研究表明,EGFR突变阳性(EGFR+)与生长显著相关,而四重阴性状态与无生长相关(图4)。这一发现也得到了四重阴性状态与病理性非浸润性相关结果的支持。

EGFR突变患者和GGN患者的临床特征似乎相似,因为EGFR+的GGN占所有GGN的大多数。正如我们在表1中总结的那样,GGN在非吸烟者和女性中更多。因为GGN往往是腺癌或其浸润前病变,GGN和EGFR突变具有相同的特征:非吸烟者、女性和腺癌。另外由于人种差异,GGN在东亚地区可能比其他地方更多,尤其是EGFR突变体GGNs,但是目前没有这方面的数据。

KRAS突变

高加索人肺腺癌KRAS突变的一般发病率约为26%(670/2,529),但吸烟者的突变发生率(34%)往往高于不吸烟者(6%)[21]。在亚洲人中,所有病例中仅检测到8%(429/5,125)的KRAS突变[22]。

当Sakamoto等检查了侵袭性病变和侵袭性腺癌各阶段的KRAS突变,大多数KRAS突变肿瘤被分类为AAH。具体AAH、AIS和MIA中KRAS突变的发生率分别为33%、12%和8%[23]。在另一项研究中观察到类似的趋势,在上述腺癌的每个阶段中KRAS检出率分别为27%、17%和10%[24]。考虑到肺腺癌中KRAS突变的总体频率在13%左右[25],如果不假设某些肿瘤和具有KRAS突变的肿瘤前病变发生自发消退,则无法解释这些发现。这个假设最初是由Yatabe等提出的[26]。一种可能的机制可能与KRAS的双重作用有关。致癌基因Ras通过p53-p21 WAF和p16INK4A-视网膜母细胞瘤肿瘤抑制途径的激活而引起退化[27-28]。另一个可能的解释是,并非所有KRAS突变体AAH都是相同的,这种差异可能来自起源细胞。在使用基因工程小鼠模型的分析中,并非所有KRAS突变肺细胞都同样允许转化:不管周围的微环境或炎症刺激如何,只有表面活性蛋白C阳性的肺泡Ⅱ型细胞能够维持KRAS驱动的AAH形成,则其中一些进展为腺瘤和恶性腺癌[29-30]。此外,体内表达KRAS的AAH的转录分析显示,只有一部分保留了晚期肺腺癌的特征,而其他部分显示出与正常肺泡细胞相当的转录特征[31]。在临床和放射学方面,CT图像上的KRAS突变GGN似乎非常相似或相同。然而,这些结节的起源可能不相同,这种差异可能导致不同的生物学行为:一些逐渐生长,而另一些则保持不变或消失。

这种看似矛盾的观察结果表明,KRAS突变在AAH中比在侵袭性腺癌中更常见,这与Sivakumar以及Sato等最近的报道一致[32]。Sivakumar等分析了来自相同患者的正常组织,AAH和侵袭性腺癌以评估肺腺癌的进展情况。然而结果显示,这些数据并未直接反映肺癌的进展情况,因为同一患者中侵袭性腺癌和成对同步GGN之间驱动突变的不一致率为80%(24/30)[33]。然而却在多达24%(4/17)的AAH中检测到KRAS突变,另外Sato等还报道了日本GGN患者中KRAS突变的频率相对较高:在17%(5/30)切除的GGN中检测到密码子12中的KRAS突变[15]。这些数据表明,并非所有KRAS突变阳性AAHs都发展为更晚期的腺癌(图4)。

BRAF突变

在高加索人大约3%(18/687)的肺腺癌中可以检测到BRAF突变,其中V600E突变约占50%[34]。BRAF突变分为3类[35]:第一类BRAF突变体(BRAF V600突变)与RAS无关并作为单体活化;第二类突变体与RAS无关,并作为二聚体激活;第三类突变体是RAS依赖性的,并且具有激酶活性。与亚洲人中KRAS突变的低频率相似,仅在0.5%(26/5,125)的亚洲人中检测到BRAF突变[22]。

在Sivakumar等的上述研究中,侵袭性腺癌中EGFR、KRAS和BRAF突变的频率分别为47%(8/17)、6%(1/17)和0%。然而,AAHs中的BRAF突变阳性率高达29%(5/17)[32]。5个AAH中有4个表现出BRAF K601E突变,另一个AAH表现出BRAF N581S突变。这些突变分别属于第二类和第三类。这些非V600E突变先前已在肺癌中被发现[36-37],并被证明是致癌驱动因子[38]。于是Sivakumar等作出假设,通过BRAF或KRAS突变的初始刺激和随后的二次突变诱导向侵袭性腺癌的进展[32]。虽然这个假设很有意思,但在这些情况下,在进展过程中必须有一个优势就是失去突变的等位基因。也就是说,KRAS或BRAF不是驱动癌基因。这一假说需要通过分析连续的活检样本来确认。

与具有KRAS突变的AAH类似,并非所有BRAF突变的AAH都发展成侵袭性腺癌,KRAS和BRAF在促分裂原活化蛋白激酶(MAPK)途径中的类似作用可能与此现象有关。

GGN的手术时机

GGN的手术标准因指南而异。根据美国胸科医师学会的指导原则,建议对符合以下任何条件的GGN进行手术切除:任何增长或实性成分进展的GGN,确认持久存在的、直径>10 mm的纯GGN,确认持久存在的、直径>8 mm的部分实性GGN,以及部分直径>15 mm的实性GGN无需随访直接手术[39]。Fleischner Society建议切除出现实性成分的纯GGN,以及增长或持久存在的部分实性结节(固体成分直径≥6mm)[16]。

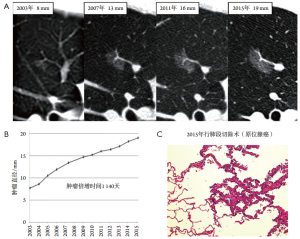

然而,对于所有显示出增长的GGN来说,是否需要立即手术是值得怀疑的。在我们的纯GGN病例中,经过12年的随访后进行了肺段切除术。虽然GGN持续生长12年,但肿瘤倍增时间长达1 140天,病理诊断显示它仍然是无侵袭性病变的AIS(图5)。尚不清楚这种类型的肿瘤何时开始侵入周围结构并威胁患者的生命以及手术是否真的有必要。因此,在老年患者中应特别考虑手术和预期寿命之间的平衡。

GGN的手术范围

放射学标准的临床试验

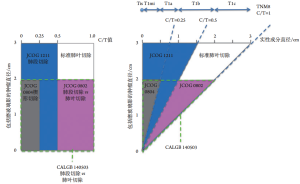

日本临床肿瘤学组(Japan Clinical Oncology Group,JCOG)进行了一项前瞻性多中心研究,以确定预测肺外周出现的临床ⅠA期肺癌的病理性非侵袭性的放射学标准(JCOG 0201)[40],其中C/T比用于评估磨玻璃组分的比例。本研究显示,病灶非侵袭性诊断的特异性分别为96.4%[病灶≤3cm,C/T值≤0.5(磨玻璃组分>50%)]和98.7%[病灶≤2cm,C/T值≤0.25(磨玻璃组分>75%)][40]。

报告了接受肺叶切除术和淋巴结清扫术的JCOG 0201试验患者的长期存活率。所有患者的总体和无复发5年生存率分别为90.6%和84.7%。当病灶≤3cm,C/T值≤0.5用作临界值时,放射性非侵袭性和侵袭性腺癌的5年总生存率分别为96.7%和88.9%(P<0.001)。使用直径≤2cm,C/T值≤0.25的病灶,放射性非侵袭性和侵袭性腺癌的5年总生存率分别为97.1%和92.4%(P=0.259)[41]。

GGN限制性手术的临床试验

虽然可手术的非小细胞肺癌的标准治疗方法是切除同侧肺门和纵隔淋巴结的肺叶切除术[42],但回顾性数据显示限制性手术也能够达到治疗效果并且创伤更小,例如GGN的肺段切除术或楔形切除术。根据JCOG 0201研究的结果,进行了3项评估限制性手术疗效的临床试验(图6)。JCOG 0802是一项Ⅲ期研究,比较肺叶切除术和肺段切除术(病灶≤2cm,C/T值>0.5)[43],与CALGB 140503试验相似[44]。JCOG 0804是一项Ⅲ期非随机验证研究,对于病灶≤2cm的肺癌楔形切除,C/T值≤0.25[45]。JCOG 1211是一项验证性Ⅲ期肺癌切除术的试验,病灶≤3cm,C/T值≤0.5[46]。

JCOG 0804的结果在ASCO 2017[47]中公布。外科手术基本上设定为楔形切除术,但当手术切缘不足(<5 mm)或肿瘤具有组织学侵入性时,允许进行肺段切除术。5年无复发生存率为99.7%,符合主要终点,未发现局部复发。

2017年对TNM分类进行了修订,关于GGN的测量,应测量CT上部分实性结节内实性成分的直径,而不是整个肿瘤大小,以便进行分期[48]。但是JCOG试验结果在第8版TNM分类中的应用有些复杂,因为JCOG试验测量的是C/T比,而TNM分类则用于直接测量固体成分(图6)。

结论

最近的临床和遗传数据标志着阐明GGN的生物学方面研究的开始。GGN经常出现在不吸烟患者中,但吸烟是结节增长的预测因子。在遗传改变方面,与不吸烟者相关的EGFR突变也是生长的预测因子,而与吸烟相关的KRAS或BRAF突变的GGN亚组可能会发生自发消退。此外,驱动基因突变阴性GGN倾向于保持不变。尽管这些数据表面上看似矛盾,但进一步的遗传分析和临床试验可能有助于更深入地了解浸润前腺癌和创伤性较小的GGNs管理策略。

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Shigeaki Moriura (Checkup Center, Daiyukai Daiichi Hospital) for providing CT images.

Funding: This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (16K19989 to Y. Kobayashi)

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Park CM, Goo JM, Lee HJ, et al. Nodular ground-glass opacity at thin-section CT: histologic correlation and evaluation of change at follow-up. Radiographics 2007;27:391-408. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:244-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi Y, Mitsudomi T. Management of ground-glass opacities: should all pulmonary lesions with ground-glass opacity be surgically resected? Transl Lung Cancer Res 2013;2:354-63. [PubMed]

- Aoki T, Tomoda Y, Watanabe H, et al. Peripheral lung adenocarcinoma: correlation of thin-section CT findings with histologic prognostic factors and survival. Radiology 2001;220:803-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsuguma H, Yokoi K, Anraku M, et al. Proportion of ground-glass opacity on high-resolution computed tomography in clinical T1 N0 M0 adenocarcinoma of the lung: A predictor of lymph node metastasis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;124:278-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakata M, Sawada S, Yamashita M, et al. Objective radiologic analysis of ground-glass opacity aimed at curative limited resection for small peripheral non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;129:1226-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hiramatsu M, Inagaki T, Inagaki T, et al. Pulmonary ground-glass opacity (GGO) lesions-large size and a history of lung cancer are risk factors for growth. J Thorac Oncol 2008;3:1245-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang B, Hwang JH, Choi YH, et al. Natural history of pure ground-glass opacity lung nodules detected by low-dose CT scan. Chest 2013;143:172-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi Y, Fukui T, Ito S, et al. How long should small lung lesions of ground-glass opacity be followed? J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:309-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee SW, Leem CS, Kim TJ, et al. The long-term course of ground-glass opacities detected on thin-section computed tomography. Respir Med 2013;107:904-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsuguma H, Mori K, Nakahara R, et al. Characteristics of subsolid pulmonary nodules showing growth during follow-up with CT scanning. Chest 2013;143:436-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho J, Kim ES, Kim SJ, et al. Long-Term Follow-up of Small Pulmonary Ground-Glass Nodules Stable for 3 Years: Implications of the Proper Follow-up Period and Risk Factors for Subsequent Growth. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1453-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kakinuma R, Noguchi M, Ashizawa K, et al. Natural History of Pulmonary Subsolid Nodules: A Prospective Multicenter Study. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1012-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JH, Park CM, Lee SM, et al. Persistent pulmonary subsolid nodules with solid portions of 5 mm or smaller: Their natural course and predictors of interval growth. Eur Radiol 2016;26:1529-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sato Y, Fujimoto D, Morimoto T, et al. Natural history and clinical characteristics of multiple pulmonary nodules with ground glass opacity. Respirology 2017;22:1615-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- MacMahon H, Naidich DP, Goo JM, et al. Guidelines for Management of Incidental Pulmonary Nodules Detected on CT Images: From the Fleischner Society 2017. Radiology 2017;284:228-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi Y, Sakao Y, Deshpande GA, et al. The association between baseline clinical-radiological characteristics and growth of pulmonary nodules with ground-glass opacity. Lung Cancer 2014;83:61-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi Y, Mitsudomi T, Sakao Y, et al. Genetic features of pulmonary adenocarcinoma presenting with ground-glass nodules: the differences between nodules with and without growth. Ann Oncol 2015;26:156-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Remy-Jardin M, Edme JL, Boulenguez C, et al. Longitudinal follow-up study of smoker's lung with thin-section CT in correlation with pulmonary function tests. Radiology 2002;222:261-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alexandrov LB, Ju YS, Haase K, et al. Mutational signatures associated with tobacco smoking in human cancer. Science 2016;354:618-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dogan S, Shen R, Ang DC, et al. Molecular epidemiology of EGFR and KRAS mutations in 3,026 lung adenocarcinomas: higher susceptibility of women to smoking-related KRAS-mutant cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:6169-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li S, Li L, Zhu Y, et al. Coexistence of EGFR with KRAS, or BRAF, or PIK3CA somatic mutations in lung cancer: a comprehensive mutation profiling from 5125 Chinese cohorts. Br J Cancer 2014;110:2812-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto H, Shimizu J, Horio Y, et al. Disproportionate representation of KRAS gene mutation in atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, but even distribution of EGFR gene mutation from preinvasive to invasive adenocarcinomas. J Pathol 2007;212:287-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoshida Y, Shibata T, Kokubu A, et al. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in atypical adenomatous hyperplasia and bronchioloalveolar carcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer 2005;50:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, et al. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in lung cancer: biological and clinical implications. Cancer Res 2004;64:8919-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yatabe Y, Borczuk AC, Powell CA. Do all lung adenocarcinomas follow a stepwise progression? Lung Cancer 2011;74:7-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Collado M, Gil J, Efeyan A, et al. Tumour biology: senescence in premalignant tumours. Nature 2005;436:642. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karnoub AE, Weinberg RA. Ras oncogenes: split personalities. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008;9:517-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mainardi S, Mijimolle N, Francoz S, et al. Identification of cancer initiating cells in K-Ras driven lung adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:255-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sutherland KD, Song JY, Kwon MC, et al. Multiple cells-of-origin of mutant K-Ras-induced mouse lung adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:4952-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ambrogio C, Gomez-Lopez G, Falcone M, et al. Combined inhibition of DDR1 and Notch signaling is a therapeutic strategy for KRAS-driven lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Med 2016;22:270-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sivakumar S, Lucas FAS, McDowell TL, et al. Genomic Landscape of Atypical Adenomatous Hyperplasia Reveals Divergent Modes to Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2017;77:6119-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu C, Zhao C, Yang Y, et al. High Discrepancy of Driver Mutations in Patients with NSCLC and Synchronous Multiple Lung Ground-Glass Nodules. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:778-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paik PK, Arcila ME, Fara M, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with lung adenocarcinomas harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2046-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yao Z, Yaeger R, Rodrik-Outmezguine VS, et al. Tumours with class 3 BRAF mutants are sensitive to the inhibition of activated RAS. Nature 2017;548:234-8. [PubMed]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014;511:543-50. Erratum in: Nature 2014;514:262. Rogers, K [corrected to Rodgers, K]. Author Correction: Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. [Nature. 2018]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marchetti A, Felicioni L, Malatesta S, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3574-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nieto P, Ambrogio C, Esteban-Burgos L, et al. A Braf kinase-inactive mutant induces lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 2017;548:239-43. [PubMed]

- Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013;143:e93S-120S.

- Suzuki K, Koike T, Asakawa T, et al. A prospective radiological study of thin-section computed tomography to predict pathological noninvasiveness in peripheral clinical IA lung cancer (Japan Clinical Oncology Group 0201). J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:751-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Asamura H, Hishida T, Suzuki K, et al. Radiographically determined noninvasive adenocarcinoma of the lung: survival outcomes of Japan Clinical Oncology Group 0201. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;146:24-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60:615-22; discussion 622-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- A phase III randomised trial of lobectomy versus limited resection (segmentectomy) for small (2 cm or less) peripheral non-small cell lung cancer (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L) [University hospital medical information network web site]. Accessed January 7, 2018. Available online: https://upload.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000002300

- A Phase III Randomized Trial of Lobectomy Versus Sublobar Resection for Small (≤ 2 cm) Peripheral Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Accessed January 17, 2018. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00499330

- A phase III non-randomized confirmatory study of Limited Surgical Resection for Peripheral Early Lung Cancer Defined with Thoracic Thin-section Computed Tomography (JCOG0804/WJOG4507L). Accessed January 17, 2018. Available onine: https://upload.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000002262

- A phase III Confirmatory Trial of Segmentectomy for Clinical T1N0 Lung Cancer Dominant with Ground Glass Opacity based on Thin-section Computed Tomography (JCOG1211). Accessed January 17, 2018. Available online: https://upload.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000013286

- Suzuki K, Watanabe S, Wakabayashi M, et al. A nonrandomized confirmatory phase III study of sublobar surgical resection for peripheral ground glass opacity dominant lung cancer defined with thoracic thin-section computed tomography (JCOG0804/WJOG4507L). J Clin Oncol 2017:35: abstr 8561.

- Travis WD, Asamura H, Bankier AA, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Coding T Categories for Subsolid Nodules and Assessment of Tumor Size in Part-Solid Tumors in the Forthcoming Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification of Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1204-23.

甘向峰

中山大学附属第五医院(更新时间:2021.7)

AME编辑部

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)