Treatment strategy for patients with relapsed small-cell lung cancer: past, present and future

Although the incidence rate of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) has consequently decreased, SCLC still accounts for approximately 13% of all lung cancers (1). SCLC is sensitive to chemotherapy and radiation therapy. However, disease relapse or progression will occur in almost all patients with SCLC. Because patients with relapsed SCLC has poor prognosis and the number of available drugs is limited, more effective second-line chemotherapy is warranted.

Zhao et al. retrospectively reported the efficiency of second-line treatment for relapsed SCLC in Translational Lung Cancer Research. They analyzed the efficacy of four drugs that were used in second-line chemotherapy: topotecan, irinotecan, paclitaxel, and docetaxel. All patients received platinum and etoposide as the first-line regimen. Although there was no significant difference in patient characteristics, the proportions of patients with limited-stage disease and a longer treatment-free interval (TFI) were higher in the irinotecan group. In addition, all patients in the paclitaxel group received platinum as second-line chemotherapy. The median progression-free survival (PFS) times for patients treated with irinotecan, topotecan, paclitaxel, and docetaxel were 91, 74.5, 81, and 50 days, respectively, with no significant differences among the treatments (P=0.6445). The median survival time (MST) of these groups were 595, 154, 168.5, and 184 days, respectively, and there were significant differences among the groups (P=0.0069). In addition to assessment of second-line treatment, they also assessed the prognostic factors for patients with relapsed SCLC. TFI <90 days, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) ≥225 U/L, and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio ≥3.5 were identified as prognostic factors in patients with relapsed SCLC received second-line treatment. They concluded that second-line chemotherapy with topotecan may provide better overall survival benefits in patients with SCLC. Although I thought that topotecan was a mistake for irinotecan, it was considered that the patient characteristics had a significant effect on the efficacy of second-line treatment, as mentioned by the authors. However, it is difficult to conduct a study comparing these drugs, and real-world data such as those discussed in this study are worthwhile.

The efficacy of second-line chemotherapy is different according to TFI and relapse is conventionally defined as sensitive and refractory or resistant based on TFI. The prognosis of patients with refractory relapsed SCLC was worse than those with sensitive relapsed SCLC. There have been few phase III trials of patients with relapsed SCLC. The results of phase III trial comparing oral topotecan with best supportive care (BSC) were reported in 2006 (2). Topotecan significantly prolonged MST compared with BSC [MST: 25.9 versus 13.9 weeks, hazard ratio (HR) =0.64, 95% confidence interval: 0.45–0.90, P=0.0104]. Amrubicin is a synthetic 9-amino-anthracycline that produced response rates of 40–50% in phase II trials (3,4). However, a phase III trial comparing topotecan with amrubicin in second-line setting did not show the superiority of amrubicin (5). The MST in the amrubicin arm was 7.5 months, compared with 7.8 months for the topotecan arm (HR =0.880, P=0.170). Although it was a subgroup analysis, amrubicin significantly prolonged MST compared with the effects of topotecan among patients with refractory relapsed SCLC (HR =0.766, P=0.047). In 2016, the results of a phase III trial comparing cisplatin, etoposide, and irinotecan combination therapy (PEI) with topotecan for patients with sensitive relapsed SCLC were reported (6). The MST of PEI group was 18.2 months and MST of topotecan group was 12.5 months. PEI significantly prolonged MST (HR =0.67, P=0.0079). Although PEI is the only treatment strategy that has displayed superiority over topotecan, PEI is rarely used in the world because of the complexity of dosing schedule and topotecan remains the control arm in many clinical trials of sensitive relapsed SCLC.

In the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline, patients with relapsed SCLC are recommended to participate in clinical trials (7). As selectable drugs other than topotecan, irinotecan, paclitaxel, docetaxel, temozolomide, and nivolumab are recommended for relapsed SCLC with TFI ≤6 months and performance status of 0–2. However, no phase III results are available for these drugs, and there is little evidence supporting their clinical use. Table 1 presents the efficacy of various drugs for patients with relapsed SCLC. Individual cytotoxic drugs had low efficacy excluding topotecan, which displayed superiority over BSC in a phase III trial. The MST of individual drugs ranged 3–7 months. The efficacy of combinations of cytotoxic drugs was also reported. However, toxicity was enhanced, and the efficacy was limited. Targeted drugs, such as bevacizumab, nintedanib, sunitinib, linsitinib, and pazopanib, were less effective, and the primary endpoint was not met (27,32,39,41,42,45,47). Although a trial of immune checkpoint inhibitors did not meet the primary endpoint of overall response rate (ORR), the drugs were linked to long durations of response (41). Recently, a phase III trial (IMpower 133) demonstrated that the addition of atezolizumab to chemotherapy for patients with untreated extensive stage SCLC significantly prolonged PFS compared with the effects of chemotherapy alone (50). These data suggested that immune checkpoint inhibitors are effective in some patients with relapsed SCLC.

Full table

It was reported that patients with sensitive relapsed SCLC responded to the same initial chemotherapy, generally termed rechallenge chemotherapy. Rechallenge chemotherapy is recommended for relapsed SCLC among patients with TFI >6 months in the NCCN guideline (7). In 1988, Giaccone et al. and Postmus et al. were reported the efficacy of rechallenge chemotherapy for patients with sensitive relapsed SCLC in 1988 (51,52). The ORR of rechallenge chemotherapy was 50–62%. Although the results of their reports suggest the efficacy of rechallenge chemotherapy, reported chemotherapy are not standard regimens at this time. In 2015, a randomize phase II trial assessing the efficacy of amrubicin and rechallenge chemotherapy for patients with sensitive relapsed SCLC was reported (33). The primary endpoint was ORR and only amrubicin group met the primary endpoint (Amrubicin group: 67% and rechallenge chemotherapy group: 43%).

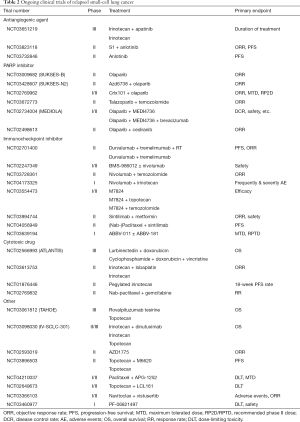

Recently, molecular targeted drugs and immune checkpoint inhibitors have been developed for SCLC, and many clinical trials of patients with relapsed SCLC are ongoing (Table 2). New drugs for SCLC are classified into six types according to the mechanism of action as follows: antiangiogenic agents, poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, immune checkpoint inhibitors, inhibitors of cell cycle proteins such as Wee1 and Aurora kinase A, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) targeting delta-like canonical Notch ligand 3 (DLL3), and enhancer of zeste homologue (EZH2) inhibitors. PARP plays an important role in repair of single-strand DNA breaks (53). It was reported that PARP protein was upregulated in SCLC compared with its expression in other lung cancers, and SCLC cell lines were sensitive to PARP inhibitors (54). In a randomized phase II study, veliparib in combination with cisplatin and etoposide significantly prolonged PFS compared with the effects of placebo combined with cisplatin and etoposide. Many trials of PARP inhibitors are ongoing. EZH2 is the enzymatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase subunit of polycomb repressive complex 2, and it mediates histone H3 lysine 27 dimethylation and trimethylation (H3K27me2 and H3K27me3, respectively) (55). EZH2 is frequently overexpressed in many types of tumors, and higher EZH2 expression is associated with the activity of cancer (56). It was reported that EZH2 was associated with chemoresistance in patient-derived xenografts (57). According to Table 2, AZD1775 is a Wee1 inhibitor, rovalpituzumab tesirine is an ADC-targeting DLL3, and PF-06821497 is an EZH2 inhibitor. Because more effective treatments for patients with relapsed SCLC are desired, the results of these clinical trials are awaited.

Full table

Acknowledgments

The author thank Joe Barber Jr., PhD, from Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanzgroup.com/) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr.2020.03.10). KW reports personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd., personal fees from Ono Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd., personal fees from Boeringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from MSD, personal fees from Taiho Pharma, personal fees from AstraZeneca K.K., outside the submitted work.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, et al. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4539-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Brien ME, Ciuleanu TE, Tsekov H, et al. Phase III trial comparing supportive care alone with supportive care with oral topotecan in patients with relapsed small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:5441-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inoue A, Sugawara S, Yamazaki K, et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing amrubicin with topotecan in patients with previously treated small-cell lung cancer: North Japan Lung Cancer Study Group Trial 0402. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5401-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Onoda S, Masuda N, Seto T, et al. Phase II trial of amrubicin for treatment of refractory or relapsed small-cell lung cancer: Thoracic Oncology Research Group Study 0301. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:5448-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Pawel J, Jotte R, Spigel DR, et al. Randomized phase III trial of amrubicin versus topotecan as second-line treatment for patients with small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:4012-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goto K, Ohe Y, Shibata T, et al. Combined chemotherapy with cisplatin, etoposide, and irinotecan versus topotecan alone as second-line treatment for patients with sensitive relapsed small-cell lung cancer (JCOG0605): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1147-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalemkerian GP, Loo BW, Akerley W, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018;16:1171-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ardizzoni A, Hansen H, Dombernowsky P, et al. Topotecan, a new active drug in the second-line treatment of small-cell lung cancer: a phase II study in patients with refractory and sensitive disease. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Early Clinical Studies Group and New Drug Development Office, and the Lung Cancer Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:2090-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Pawel J, Schiller JH, Shepherd FA, et al. Topotecan versus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine for the treatment of recurrent small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:658-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takeda K, Negoro S, Sawa T, et al. A phase II study of topotecan in patients with relapsed small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2003;4:224-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jotte R, Conkling P, Reynolds C, et al. Randomized phase II trial of single-agent amrubicin or topotecan as second-line treatment in patients with small-cell lung cancer sensitive to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:287-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ettinger DS, Jotte R, Lorigan P, et al. Phase II study of amrubicin as second-line therapy in patients with platinum-refractory small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2598-603. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murakami H, Yamamoto N, Shibata T, et al. A single-arm confirmatory study of amrubicin therapy in patients with refractory small-cell lung cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study (JCOG0901). Lung Cancer 2014;84:67-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masuda N, Fukuoka M, Kusunoki Y, et al. CPT-11: a new derivative of camptothecin for the treatment of refractory or relapsed small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1992;10:1225-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto N, Tsurutani J, Yoshimura N, et al. Phase II study of weekly paclitaxel for relapsed and refractory small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res 2006;26:777-81. [PubMed]

- Smit EF, Fokkema E, Biesma B, et al. A phase II study of paclitaxel in heavily pretreated patients with small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 1998;77:347-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pietanza MC, Kadota K, Huberman K, et al. Phase II trial of temozolomide in patients with relapsed sensitive or refractory small cell lung cancer, with assessment of methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase as a potential biomarker. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:1138-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zauderer MG, Drilon A, Kadota K, et al. Trial of a 5-day dosing regimen of temozolomide in patients with relapsed small cell lung cancers with assessment of methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase. Lung Cancer 2014;86:237-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jassem J, Karnicka-Mlodkowska H, van Pottelsberghe C, et al. Phase II study of vinorelbine (Navelbine) in previously treated small cell lung cancer patients. EORTC Lung Cancer Cooperative Group. Eur J Cancer 1993;29A:1720-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Furuse K, Kubota K, Kawahara M, et al. Phase II study of vinorelbine in heavily previously treated small cell lung cancer. Japan Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Study Group. Oncology 1996;53:169-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson DH, Greco FA, Strupp J, et al. Prolonged administration of oral etoposide in patients with relapsed or refractory small-cell lung cancer: a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 1990;8:1613-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Lee I, Smit EF, van Putten JW, et al. Single-agent gemcitabine in patients with resistant small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2001;12:557-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masters GA, Declerck L, Blanke C, et al. Phase II trial of gemcitabine in refractory or relapsed small-cell lung cancer: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial 1597. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1550-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lammers PE, Shyr Y, Li CI, et al. Phase II study of bendamustine in relapsed chemotherapy sensitive or resistant small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:559-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kudo K, Ohyanagi F, Horiike A, et al. A phase II study of S-1 in relapsed small cell lung cancer. Mol Clin Oncol 2013;1:263-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nogami N, Hotta K, Kuyama S, et al. A phase II study of amrubicin and topotecan combination therapy in patients with relapsed or extensive-disease small-cell lung cancer: Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group Trial 0401. Lung Cancer 2011;74:80-4. [PubMed]

- Schuette W, Nagel S, Juergens S, et al. Phase II trial of gemcitabine/irinotecan in refractory or relapsed small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2005;7:133-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rocha-Lima CM, Herndon JE 2nd, Lee ME, et al. Phase II trial of irinotecan/gemcitabine as second-line therapy for relapsed and refractory small-cell lung cancer: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study 39902. Ann Oncol 2007;18:331-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohyanagi F, Horiike A, Okano Y, et al. Phase II trial of gemcitabine and irinotecan in previously treated patients with small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2008;61:503-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam SS, Foster J, Gooding W, et al. Phase 2 study of irinotecan and paclitaxel in patients with recurrent or refractory small cell lung cancer. Cancer 2010;116:1344-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ando M, Kobayashi K, Yoshimura A, et al. Weekly administration of irinotecan (CPT-11) plus cisplatin for refractory or relapsed small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2004;44:121-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Naka N, Kawahara M, Okishio K, et al. Phase II study of weekly irinotecan and carboplatin for refractory or relapsed small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2002;37:319-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inoue A, Sugawara S, Maemondo M, et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing amrubicin with re-challenge of platinum doublet in patients with sensitive-relapsed small-cell lung cancer: North Japan Lung Cancer Study Group trial 0702. Lung Cancer 2015;89:61-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goto K, Sekine I, Nishiwaki Y, et al. Multi-institutional phase II trial of irinotecan, cisplatin, and etoposide for sensitive relapsed small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2004;91:659-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spigel DR, Waterhouse DM, Lane S, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral topotecan and bevacizumab combination as second-line treatment for relapsed small-cell lung cancer: an open-label multicenter single-arm phase II study. Clin Lung Cancer 2013;14:356-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Allen JW, Moon J, Redman M, et al. Southwest Oncology Group S0802: a randomized, phase II trial of weekly topotecan with and without ziv-aflibercept in patients with platinum-treated small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2463-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trafalis DT, Alifieris C, Stathopoulos GP, et al. Phase II study of bevacizumab plus irinotecan on the treatment of relapsed resistant small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2016;77:713-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jalal S, Bedano P, Einhorn L, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab in patients with chemosensitive relapsed small cell lung cancer: a safety, feasibility, and efficacy study from the Hoosier Oncology Group. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:2008-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mountzios G, Emmanouilidis C, Vardakis N, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab in patients with chemoresistant relapsed small cell lung cancer as salvage treatment: a phase II multicenter study of the Hellenic Oncology Research Group. Lung Cancer 2012;77:146-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han JY, Kim HY, Lim KY, et al. A phase II study of nintedanib in patients with relapsed small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2016;96:108-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ready NE, Ott PA, Hellmann MD, et al. Nivolumab Monotherapy and Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Recurrent Small Cell Lung Cancer: Results From the CheckMate 032 Randomized Cohort. J Thorac Oncol 2020;15:426-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim YJ, Keam B, Ock CY, et al. A phase II study of pembrolizumab and paclitaxel in patients with relapsed or refractory small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2019;136:122-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pietanza MC, Waqar SN, Krug LM, et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase II Study of Temozolomide in Combination With Either Veliparib or Placebo in Patients With Relapsed-Sensitive or Refractory Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2386-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farago AF, Yeap BY, Stanzione M, et al. Combination Olaparib and Temozolomide in Relapsed Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov 2019;9:1372-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han JY, Kim HY, Lim KY, et al. A phase II study of sunitinib in patients with relapsed or refractory small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2013;79:137-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chiappori AA, Otterson GA, Dowlati A, et al. A Randomized Phase II Study of Linsitinib (OSI-906) Versus Topotecan in Patients With Relapsed Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Oncologist 2016;21:1163-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koinis F, Agelaki S, Karavassilis V, et al. Second-line pazopanib in patients with relapsed and refractory small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre phase II study of the Hellenic Oncology Research Group. Br J Cancer 2017;117:8-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rudin CM, Hann CL, Garon EB, et al. Phase II study of single-agent navitoclax (ABT-263) and biomarker correlates in patients with relapsed small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:3163-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morgensztern D, Besse B, Greillier L, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Rovalpituzumab Tesirine in Third-Line and Beyond Patients with DLL3-Expressing, Relapsed/Refractory Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Results From the Phase II TRINITY Study. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:6958-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczesna A, et al. First-Line Atezolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2220-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giaccone G, Ferrati P, Donadio M. European Journal of Cancer and Clinical Oncology 1987;23:1697-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Postmus PE, Berendsen HH, van Zandwijk N, et al. Retreatment with the induction regimen in small cell lung cancer relapsing after an initial response to short term chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1987;23:1409-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rouleau M, Patel A, Hendzel MJ, et al. PARP inhibition: PARP1 and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer 2010;10:293-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Byers LA, Wang J, Nilsson MB, et al. Proteomic profiling identifies dysregulated pathways in small cell lung cancer and novel therapeutic targets including PARP1. Cancer Discov 2012;2:798-811. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Margueron R, Reinberg D. The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature 2011;469:343-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang CJ, Hung MC. The role of EZH2 in tumour progression. Br J Cancer 2012;106:243-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gardner EE, Lok BH, Schneeberger VE, et al. Chemosensitive Relapse in Small Cell Lung Cancer Proceeds through an EZH2-SLFN11 Axis. Cancer Cell 2017;31:286-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]