TFAP2A-activated ITGB4 promotes lung adenocarcinoma progression and inhibits CD4+/CD8+ T-cell infiltrations by targeting NF-κB signaling pathway

Highlight box

Key findings

• Integrin β4 (ITGB4) is an oncogene for lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD).

What is known and what is new?

• Upregulation of ITGB4 has been observed in various malignant tumors, including glioma, gastric and cervical cancer. In lung cancer, aberrant ITGB4 expression was associated with decreased overall survival. However, the specific functions and underlying mechanisms of ITGB4 in LUAD progression are yet to be fully elucidated.

• Functional assays indicated that ITGB4 could promote LUAD progression in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, ITGB4 could activate the NF-κB signaling pathway by interacting with IκBα. Additionally, ITGB4 could suppress CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltrations in LUAD cells. Lastly, TFAP2A could directly bind to the ITGB4 promoter and transcriptionally activate ITGB4 in LUAD cells.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• ITGB4 exerts an oncogenic role in LUAD. It may serve as a potential immunotherapeutic target of LUAD.

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death globally, comprising 18% of total cancer deaths (1). Among the various subtypes of lung cancer, lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most prevalent one, accounting for around 40% of all lung cancer cases (2). Although advancements in cancer immunotherapy have improved the prognosis of LUAD patients, the 5-year survival rate of patients remains low (3,4).

The tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) plays crucial roles in the progression of malignant tumors (5). Among the immune cells in the TIME, T cells represent the prevalent cell type and are closely associated with cancer immunotherapy (6,7). In lung cancer, higher CD3+, CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell infiltrations are associated with a favorable prognosis (8-12). In recent years, immunotherapies have shown unexpected superiority to conventional chemotherapies in LUAD (13). However, due to the resistance to immunotherapy, the overall response rate of anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) treatment remains only ~15% (14). Additionally, the occurrence of severe immune-related adverse events has significantly impacted treatment effectiveness (15). Therefore, identification of novel immune-associated genes that affect the progression and TIME of LUAD may be of great importance.

Immune-associated genes play fundamental roles in regulating tumor progression and immune responses. In a previous study, a total of 770 immune-associated genes were provided by nCounter® PanCancer Immune Profiling Panel (NanoString), a unique 770-plex gene expression panel measuring tumor immune responses based on NanoString technology (Seattle, USA) (16). The platform provides a detailed list of these immune-related genes along with probe information and sufficient functional annotations. Their important role in tumor progression has been widely established. For instance, Lu et al. demonstrated that NLRP3 promoted lymphoma growth and suppressed anti-tumor immunity by upregulating PD-L1 in the tumor microenvironment (17). Ma et al. revealed that IL-17A exerted a tumor-promoting effect by suppressing CD8+ T-cell responses (18). Tosti and colleagues demonstrated that the immune-associated gene IL22 was produced by CD4+ and CD8+ polyfunctional T cells and was associated with a favorable clinical outcome by enhancing T-cell responses in colorectal cancer (19). These studies collectively emphasize the critical roles of immune-associated genes in tumor progression and the immune microenvironment. In this research, we conducted a thorough analysis aimed at identifying novel immune-associated genes that influence the progression and TIME of LUAD. Among these genes, integrin β4 (ITGB4) was notably up-regulated in LUAD and linked to an unfavorable prognosis. Therefore, we speculate that ITGB4 may act as an oncogenic gene to promote the progression of lung adenocarcinoma and inhibit tumor immunity. However, its specific function and mechanism need further investigation.

Functional experiments and animal models were conducted to elucidate the role of ITGB4 in promoting the progression of lung adenocarcinoma both in vivo and in vitro. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis, and western blot assays were employed to unveil ITGB4’s capacity to activate the NF-κB signaling pathway. Immunoprecipitation (IP) assays, mass spectrometry analysis, and co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays demonstrated direct binding between ITGB4 and IκBα, a pivotal protein in the NF-κB pathway. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of lung adenocarcinoma samples and an immunocompetent mouse model showcased ITGB4’s ability to suppress CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltrations in LUAD cells. Luciferase reporter assays and chromatin IP (ChIP) assays unveiled TFAP2A’s direct binding to the ITGB4 promoter, thereby transcriptionally activating ITGB4 in LUAD cells.

In this study, we hypothesized that transcription factor TFAP2A-activated ITGB4 may promote lung adenocarcinoma progression and inhibit CD4+/CD8+ T-cell infiltrations through targeting NF-κB signaling pathway by interacting with IκBα. ITGB4 may serve as a potential immunotherapeutic target of LUAD. We present this article in accordance with the MDAR reporting checklist (available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-50/rc).

Methods

Patients and tissue specimens

In the present study, the transcriptome data of 57 paired LUAD samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) and 15 paired LUAD samples from GSE31210 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds) were used to screen differentially expressed genes. Survival analysis was performed based on 500 patients with LUAD from TCGA and 226 patients with LUAD from GSE31210. A total of 20 paired LUAD samples were collected from The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University between January 2019 and January 2020. All patients were diagnosed with primary LUAD and had not received any type of preoperative anti-tumor therapies. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants. All the procedures involving patient samples were compliant with all relevant ethical regulations and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Approval No. 2019-SR-123). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The characteristics of the study subjects are shown in Table S1.

RNA-seq

Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Then, RNA was treated using a Ribo-off rRNA Depletion Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) to remove ribosomal RNA before generating the RNA-seq library. The RNA-seq library was deep sequenced with an illumina NovaseqTM6000 instrument (illumina, San Diego, USA). The reads were mapped to the human reference genome (Homo sapiens. GRCh38). Bcl2FastQ, FastQC, and DESeq were used for data processing and analyses.

Cell culture

A human normal bronchial cell line 16HBE (CVCL_0112), five human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines H1299 (CVCL_0060), H1975 (CVCL_1511), A549 (CVCL_0023), H358 (CVCL_1559), PC9 (CVCL_B260), and a Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC; LL/2) (CVCL_4358) cell line were obtained from the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China. All cell lines were tested by short tandem repeat (STR) (Shanghai Zhong Qiao Xin Zhou Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured in the RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). All cell lines were incubated at 37 ℃ with 5% CO2.

Plasmid construction, small interfering RNA (siRNA) interference and lentiviral infection

To construct ITGB4-overexpressing plasmids (named ITGB4 OE), human ITGB4 complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized and cloned into the pcDNA3.1(+) vector (Invitrogen), while empty plasmids were used as a control (named vector). Transfection was performed with Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen).

ITGB4-knockdown lentivirus was designed and constructed by Shanghai GeneChem (Shanghai, China). Short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) against ITGB4 were cloned into the GV248 lentiviral vector (GeneChem). The scrambled shRNA sequence was also cloned into the GV248 vector and was used as a negative control [named sh-negative control (sh-NC)]. The lentivirus vectors were transfected into A549, PC9, and LLC cells using 7 µg/mL polybrene (Sigma, St. Louis, USA). Following transfection for 2 days, the cells were subjected to selection with 3 µg/mL puromycin (Sigma) for 2 weeks to establish stable cell lines exhibiting ITGB4 knockdown.

The siRNAs (named si-TFAP2A) and overexpression plasmid for TFAP2A (named TFAP2A OE) were synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China) and transfected as aforementioned. All the sequences used in the present study are listed in Table S2. Sh-ITGB4#1 (human) (named sh-ITGB4) and sh-ITGB4 (mouse) (named LLC-sh-ITGB4) were utilized in in vivo assays.

RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assays

Total RNA was extracted from the cell lines using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed using a PrimeScript Reverse Transcription Kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan) according to the instructions. qRT-PCR was conducted on a StepOnePlusTM Real-Time PCR System (Thermo, Waltham, USA). Relative mRNA expression, normalized to β-actin, was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The primers utilized in this study are listed in Table S3.

Protein isolation and western blot assays

Total protein was isolated from A549 and PC9 cells using RIPA buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Bicinchoninic acid assay (KeyGEN, Nanjing, China) was used to determine the protein concentration. After being separated by the sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), the lysates of protein were transferred to the polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Then, the membranes were incubated at 4 ℃ overnight with specific primary antibodies. Afterwards, the blots were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody for 2 hours. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate kit (NCM Biotech, Suzhou, China). The antibodies utilized in this study are listed in Table S4.

Subcellular fractionation

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions from A549 and PC9 cells were isolated using Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s descriptions. The subcellular localization of proteins was determined by western blotting. Anti-Lamin B1 antibody and anti-GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) antibody were used as loading controls for the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, respectively.

Co-IP assay, IP assay and mass spectrometry

Co-IP assays were conducted using the Pierce Co-IP kit (Thermo) according to the manufacturer’s descriptions. Cell extracts were prepared in IP lysis buffer and incubated overnight at 4 ℃ with either immunoglobulin G (IgG) (5 µg) or primary antibodies (5 µg), including anti-ITGB4 antibody and anti-IκBα antibody. Total extracts were then incubated with protein A/G agarose beads (Thermo) for 2 hours. The protein A/G agarose beads were collected and washed with lysis buffer. Immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blot assays as described above.

In addition, IP assay was also performed using the Pierce Co-IP kit (Thermo). A549 cell extracts were prepared in IP lysis buffer and incubated overnight at 4 ℃ with either anti-IgG or anti-ITGB4 antibodies (5 µg). Total extracts were then incubated with protein A/G agarose beads (Thermo) for 2 hours. The beads were subsequently washed thoroughly, and the IP proteins were analyzed by mass spectrometry (Applied Protein Technology, Shanghai, China). Mass spectrometry was analyzed using Proteome Discoverer software with the UniProtKB human database (UniProt Homo sapiens 207393_20230103).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and colony formation assays

The CCK-8 assay was performed using the CCK-8 solution (Dojindo, Tokyo, Japan) according to a protocol of the manufacturer. Cells were seeded into 96-well plates for 2×103 cells/100 µL/well. After being incubated for 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours, the cells were treated with 10 µL/well of the CCK-8 solution to measure the cell viability at an absorbance of 450 nm using the microplate reader.

For the colony formation assay, LUAD cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1×103 cells per well and cultured in an incubator at 37 ℃ with 5% CO2 for 14 days. The colonies were set with 4% paraformaldehyde and then stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Beyotime). The number of colonies containing more than 50 cells was counted in each well. All experiments were repeated three times.

5-ethynyl-2-deoxyuridine (EdU) assay

The EdU assay kit (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) was used to assess the proliferation ability of cells following the recommendation of the manufacturer. Cells were seeded into 48-well plates and cultured for 24 hours. Then, 50 µM of EdU solution was added into the plate, and cells were incubated for 2 hours at 37 ℃ with 5% CO2. Subsequently, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Next, cells were stained with Apollo, and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used to label cell nuclei. The EdU-positive cells were observed under fluorescent microscopy and the proliferation rate was calculated in five randomly selected fields.

Cell migration and invasion assays

The migration and invasion abilities of LUAD cells were determined using transwell chambers (8 µm; Corning, Elmira, USA). Cells were seeded into 200 µL serum-free medium in the upper transwell chamber for 5×104 cells per chamber, while the lower chamber was filled with 600 µL RPMI-1640 or Dulbecco’s Modification of Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS. For cell invasion assay, the upper chamber was coated with the Matrigel (Corning), which was the only difference with cell migration assay. After 2 days of incubation, cells were set with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Beyotime). The non-migrated or non-invaded cells on the upper membrane of the insert chamber were eliminated using a cotton tip. The migrative or invasive ability of LUAD cells was determined by photographing the stained cells with an inverted microscope and counting in five randomly selected fields. All the experiments were performed in triplicate.

Wound healing assay

LUAD cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 80% confluency, and a linear scratch wound was created in the cell monolayers through a 200-µL pipette tip. Subsequently, the cells were cultured in medium without FBS. After washing the A549 and PC9 cells with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) to remove debris and floating cells, each wound was imaged at 0 and 48 hours using an inverted microscope.

ChIP assay

ChIP assay was performed using the Pierce Agarose ChIP Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the instructions of the manufacturer. A549 and PC9 cells were grown to about 90% confluence in a 10-cm culture dish and treated with 1% formaldehyde to produce DNA-protein cross-links. Cell lysates were sonicated to fragment chromatin DNA into 200–1,000 bp fragments. Equal amounts of chromatin supernatants were then subjected to IP using 2 µg of anti-TFAP2A antibody or anti-IgG antibody along with protein A/G magnetic beads. The protein/DNA complexes were subsequently de-crosslinked to release the DNA, and the enriched DNA fragments were analyzed by PCR. The sequences of the primers for ITGB4 were as follow: forward, 5'-AGGCCCCTCAGGCAAGCT-3' and reverse, 5'-GGAAGGAGTCCCAGTTTG-3'.

Luciferase reporter assay

The TFAP2A-binding motif within the promoter region of ITGB4 was identified using JASPAR (http://jaspar.genereg.net/). The ITGB4 promoter was amplified using PCR and cloned into the pGL3-basic luciferase vector (Promega Corporation, Madison, USA), and this construct was designated as ITGB4-WT. Subsequently, the TFAP2A-binding motif was removed from the ITGB4 promoter vector using PCR-mediated mutagenesis, and this construct was named ITGB4-MUT. Additionally, NF-κB luciferase reporter constructs were obtained from Promega Corporation. All vectors were verified by sequencing, and their luciferase activities were measured using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Promega Corporation).

Animal studies

All animal experiments were performed under a project license (Approval No. IACUC-2208008) granted by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University, in compliance with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University for the care and use of animals. Human endpoints were applied when mice lost 20% of their initial body weight. The well-being and behavior of the animals were monitored every 2 days throughout the study period. To ensure humane treatment, all mice were administered 2% pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection to induce deep anesthesia. Subsequently, euthanasia was performed through cervical dislocation. Specific criteria were utilized to confirm animal death, including the absence of breathing, heartbeat, corneal reflexes, muscle tone, and mucosal color. The maximum allowable tumor size throughout the study was limited to 1.5 cm3.

For the xenograft assay, 20 male BALB/c nude mice (4 weeks old) were procured from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China) and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions (temperature: 25 ℃; humidity: 50%; light/dark cycle: 12/12 hours) with access to sterilized fodder and purified water. A total of 3×106 stable cells (either A549-sh-NC or A549-sh-ITGB4) were suspended in 200 µL PBS and subcutaneously injected into the right flanks of the nude mice. The sh-ITGB4#1 was used in the following assays in vivo due to its higher knockdown efficiency. Tumor growth was monitored every 3 days, and tumor volumes were calculated using the formula: volume (cm3) =0.5 × length × width2. After a 27-day period following injection, the mice were euthanized, and the growth of subcutaneous tumors was assessed. Tumor tissues were collected and preserved for subsequent experiments.

For the pulmonary metastasis analysis, A549-sh-NC or A549-sh-ITGB4 cells were labeled with firefly luciferase. Next, 100 µL of cell suspension (2×106 cells) was injected into the tail veins of mice, with three mice in each group. Pulmonary metastasis was monitored Using a Xenogen IVIS Spectrum Imaging System (PerkinElmer, Waltham, USA). After 5 weeks, mice were sacrificed, and lungs were surgically dissected. The numbers of lung metastatic nodules were counted and validated using hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained sections by microscopy.

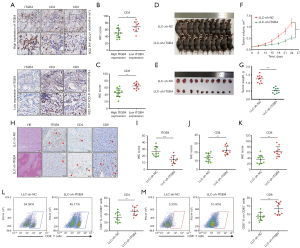

For the immunocompetent mouse model, 20 female C57BL/6J mice (6 weeks old) were purchased from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center (Chinese Academy of Sciences) and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. A total of 3×106 stable LLC-sh-NC or LLC-sh-ITGB4 cells suspended in 200 µL PBS were subcutaneously injected into the right flanks of the mice. The tumor volume was assessed every 3 days using the formula: tumor volume (cm3) =0.5 × length × width2. All the tumors were harvested and weighed 24 days after injection, and the tumor tissues were immediately preserved for further experiments.

Flow cytometric analysis of C57BL/6J mouse tumors

Tumor samples were dissociated into small fragments using scalpels, and digested in DMEM containing 2% FBS, collagenase IV (Millipore, Billerica, USA) and DNase I (Millipore). Next, the cells were filtered through a strainer (Thermo) and washed with PBS. Cell surface staining was performed in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (PBS supplemented with 2% FBS). All cells were resuspended in a diluted 100 µL antibodies solution. Next, the cells were analyzed using a CytoFLEX Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Pasadena, USA), and data were evaluated using FlowJo v10.8.1 software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA). The antibodies for mouse tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) staining were as follows: allophycocyanin (APC) anti-mouse CD4 antibody (dilution 1:100; cat. no. 100411; BioLegend, Inc., San Diego, USA), AlexaFluor-647 anti-mouse CD8a antibody (dilution 1:100; cat. no. 100727; BioLegend, Inc.) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-mouse CD45 antibody (dilution 1:100; cat. no. 157213; BioLegend, Inc.).

IHC analysis

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded specimens were sectioned into 4-µm-thick slices. After deparaffinization in xylene and gradual rehydration with ethanol, the sections were treated with citrate buffer for antigen retrieval. Subsequently, the sections were incubated overnight at 4 ℃ with the primary antibodies. Two experienced pathologists, blinded to the clinical data of the patients, independently assessed and scored the immunostained sections. Staining intensity was scored as follows: 0 (−, no staining), 1 (+, weak staining), 2 (++, moderate staining), and 3 (+++, strong staining). The IHC score, ranging from 0 to 300, was calculated by multiplying the staining intensity and the percentage of positive cells. Based on the cutoff value of 150 for ITGB4 expression in tumor tissues, the 20 patients with LUAD were divided into a high ITGB4 expression group (IHC score >150) and a low ITGB4 expression group (IHC score ≤150).

Statistical analysis

In the current study, differential gene expression analysis was performed using paired Student’s t-test. Log-rank test was adopted to evaluate the associations between immune-associated genes and LUAD prognosis. KEGG pathway enrichment and Gene Ontology (GO) analyses were performed using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8 (20). Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA was used to compare the differences between experimental groups. Pearson correlation coefficient was employed to assess the correlations between transcription factor levels and ITGB4 expression. All these statistical evaluations were completed with R 3.6.0 and GraphPad Prism (6.01). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

ITGB4 is up-regulated in LUAD tumor tissues, and patients with higher ITGB4 expression have an inferior prognosis

Out of the 770 immune-related genes from NanoString (table available at https://cdn.amegroups.cn/static/public/tlcr-24-50-1.pdf), 78 genes exhibited abnormal upregulation in both TCGA database (57 paired LUAD samples) and GSE31210 dataset (15 paired LUAD samples). Remarkably, 12 of these genes were found to be significantly associated with poor LUAD prognosis in both datasets (Figure 1A). Among them, ITGB4 was known to take part in a variety of biological processes, including immune responses, epithelial cell senescence, and airway inflammation (21-23). Based on the CancerSEA database (http://biocc.hrbmu.edu.cn/CancerSEA/), we found that ITGB4 was related to several functional aspects of LUAD cells, especially inflammation and metastasis (Figure S1). As a result, the current study focused on investigating the functions of ITGB4. Expression analysis revealed significantly higher levels of ITGB4 in LUAD tumor tissues compared with those in adjacent normal tissues in both TCGA database (Figure 1B) and the GSE31210 dataset (Figure 1C). These results were further validated in the current dataset, namely JSPH (Jiangsu Province Hospital) data, consisting of 19 paired LUAD samples (Figure 1D). Importantly, LUAD patients with higher ITGB4 expression had worse outcomes {TCGA: hazard ratio (HR) =1.61 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.21–2.18], P=0.001, Figure 1E; GSE31210: HR =2.04 (95% CI: 1.03–3.88), P=0.04, Figure 1F}. This finding was further confirmed in 69 advanced LUAD patients (stage III–IV) from the GSE68465 [HR =2.16 (95% CI: 1.40–4.00), P=0.002, Figure S2A] and 719 LUAD patients from the Kaplan-Meier plotter database (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) [HR =1.92 (95% CI: 1.53–2.44), P<0.001, Figure S2B]. Additionally, IHC performed on 20 paired LUAD samples indicated that tumor tissues had higher ITGB4 IHC scores than the adjacent normal tissues (Figure 1G,1H).

ITGB4 promotes LUAD cell proliferation, migration and invasion in vitro

The expression of ITGB4 in LUAD cell lines was significantly higher compared to the normal bronchial cell line (Figure 2A). The use of shRNAs effectively reduced ITGB4 expression, while the ITGB4 overexpression plasmid sufficiently increased ITGB4 expression (Figure 2B). The sh-ITGB4#1 (named sh-ITGB4) was used in the following assays in vivo due to its higher knockdown efficiency. The CCK-8 assay results revealed a notable decrease in the relative number of viable LUAD cells upon ITGB4 downregulation. Conversely, overexpression of ITGB4 led to a relative increase in the number of viable cells (Figure 2C,2D). Silencing of ITGB4 significantly reduced the number and size of cell colonies, while ITGB4 overexpression showed opposite effects (Figure 2E,2F). Furthermore, ITGB4 knockdown significantly inhibited the proliferation of LUAD cell in EdU assay (Figure 2G). On the contrary, ITGB4 overexpression promoted the proliferation of A549 and PC9 cells (Figure 2H). Overall, these results indicated that ITGB4 could facilitate the proliferation of LUAD cells in vitro.

In addition, transwell assay suggested that inhibition of ITGB4 significantly reduced the migration and invasion of LUAD cells (Figure 3A). Overexpression of ITGB4 led to a notable increase of their migratory and invasive abilities (Figure 3B). Consistently, in the wound healing assay, ITGB4 silencing remarkably suppressed LUAD cell migration, while ITGB4 overexpression had the opposite effects (Figure 3C,3D). These results indicated that ITGB4 could exert an oncogenic effect on the proliferation, migration and invasion of LUAD cells.

ITGB4 promotes LUAD cell tumorigenesis and metastasis in vivo

To investigate the oncogenic role of ITGB4 in LUAD tumors in vivo, a nude mouse xenograft model was established using stable A549-sh-ITGB4 cells. Knockdown of ITGB4 significantly inhibited the growth of lung adenocarcinoma xenografts (Figure 4A). Compared to the control group, the A549-sh-ITGB4 group exhibited significantly lower tumor volumes and weights (Figure 4B,4C). IHC staining showed a reduced level of Ki-67 in the ITGB4-silencing group (Figure 4D). In the tail vein tumor metastasis models, in vivo bioluminescence imaging demonstrated significantly lower fluorescence intensity and proportion in the lungs with ITGB4 inhibition (Figure 4E). Furthermore, ITGB4 knockdown resulted in a significant reduction in the number of metastatic lung nodules (Figure 4F,4G). Collectively, these findings suggest that ITGB4 could promote the growth and metastasis of LUAD tumors in vivo.

ITGB4 activates the NF-κB signaling pathway by interacting with IκBα

To investigate the molecular mechanism underlying the oncogenic role of ITGB4 in LUAD, RNA-seq analysis was performed to compare the gene transcription profiles of A549-sh-NC and A549-sh-ITGB4 cells. The analysis identified 862 up-regulated genes and 674 down-regulated genes in ITGB4-silenced cells (Figure S3). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that these differentially expressed genes were mainly enriched in the NF-κB signaling pathway, and a consistent result was observed in TCGA database (Figure 5A,5B). As expected, ITGB4 overexpression significantly increased the luciferase activity of NF-κB, whereas ITGB4 knockdown had the opposite effect (Figure 5C). Subsequent experiments demonstrated that the phosphorylated levels of proteins such as p-p65, p-IκBα and p-IKKα/β were remarkably increased upon ITGB4 overexpression but decreased after ITGB4 silencing. However, the total protein levels of these molecules remained unchanged, except for IκBα. Specifically, ITGB4 overexpression reduced the protein level of IκBα, whereas ITGB4 silencing increased it in LUAD cells (Figure 5D). Moreover, ITGB4 knockdown suppressed the nuclear translocation of p65 in both A549 and PC9 cells, while ITGB4 overexpression accelerated the nuclear translocation (Figure 5E). These findings indicated that ITGB4 could activate the NF-κB signaling pathway.

To reveal how ITGB4 promoted the activation of the NF-κB signaling, we conducted an IP assay of ITGB4 with A549 cells, and the IP proteins were subjected to mass spectrometry (Figure S4). Among the proteins identified in the IP assay (Table S5), we successfully confirmed IκBα as the protein that specifically binds to ITGB4. From the mass spectrometry data, it was determined that IκBα (also referred to as NFKBIA) was the sole protein found to be associated with the NF-κB signaling pathway. The interaction between IκBα and ITGB4 was validated through western blot analysis (Figure 5F). Additionally, co-IP assays demonstrated a direct protein-protein interaction between ITGB4 and IκBα in both A549 and PC9 cells (Figure 5G). Moreover, IHC staining performed on xenograft tumors showed an increase in IκBα expression upon ITGB4 silencing (Figure 5H). These findings suggested that ITGB4 could interact with IκBα to suppress its expression in LUAD. Previous studies have shown that IκBα could limit p65 transportation into the nucleus and block NF-κB signaling (24,25). Therefore, we speculated that ITGB4 may activate the NF-κB signaling pathway through interacting with IκBα.

To further explore the role of NF-κB signaling in the migration of LUAD cells promoted by ITGB4, the classical NF-κB inhibitor pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC) was used. Transwell and wound healing assays indicated that PDTC significantly inhibited the improved cell migration induced by ITGB4 overexpression in LUAD cells (Figure 5I,5J). These results demonstrated that NF-κB signaling may participate in the migratory phenotype induced by ITGB4 in LUAD.

Laminin-5 enhanced LUAD cell proliferation, migration and invasion through ITGB4 signaling activation

In light of ITGB4 being a well-known cell surface receptor, we further explored whether its ligand laminin-5 could activate ITGB4 signaling and promote LUAD progression. As shown in Figure 6A, laminin-5 stimulation had little effect on ITGB4 expression but significantly enhances the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Importantly, this stimulatory effect was largely attenuated by ITGB4 silencing. As expected, laminin-5 stimulation facilitated LUAD cell proliferation. Furthermore, these proliferative effects could be reversed by knocking down ITGB4 (Figure 6B,6C). Consistently, the transwell assay revealed that laminin-5 stimulation resulted in a notable increase in the migration and invasion of LUAD cells. Notably, the promotional effects were effectively reversed by ITGB4 silencing (Figure 6D,6E). Similar results were observed in the wound healing assays (Figure 6F). These results collectively suggest that laminin-5, as an ITGB4 ligand, could promote LUAD progression by activating ITGB4 signaling.

ITGB4 suppresses CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltrations in the TIME of LUAD

According to the GO analysis, ITGB4 may be involved in various immune-related processes, including the inflammatory response, innate immune response, immune system process, and immune effector process (Figure S5). Therefore, we further investigated whether ITGB4 could influence T-cell immune responses in LUAD. As shown in Figure 7A-7C, LUAD tumors with higher ITGB4 expression exhibited significantly lower infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. To further investigate the effect of ITGB4 on T-cell infiltrations in vivo, an immunocompetent mouse model was established using LLC-sh-ITGB4 cells and C57BL/6J mice. Consistently, ITGB4 knockdown markedly inhibited the proliferation, migration, and invasion abilities of LLC cells (Figure S6). In the immunocompetent mouse model, mice treated with LLC-sh-ITGB4 cells exhibited significant inhibition of tumor growth (Figure 7D-7G). Furthermore, ITGB4 knockdown increased CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltration in the mouse tumor tissues (Figure 7H-7K). Flow cytometric analysis further supported these findings, indicating an elevated population of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in CD45+ TILs following ITGB4 silencing (Figure 7L,7M). Overall, these findings suggested that ITGB4 could suppress CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltrations in the TIME of LUAD.

TFAP2A activates the transcription of ITGB4 in LUAD

In order to investigate the potential transcription factors that may activate ITGB4 transcription in LUAD, we utilized the JASPAR online database (http://jaspar.genereg.net/) and the Animal Transcription Factor Database (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/AnimalTFDB#!/). Through this analysis, we predicted 268 transcription factors that have the potential to regulate ITGB4 expression (Figure 8A). Further co-expression analysis based on the TCGA database revealed that 16 of these transcription factors showed a significant correlation with ITGB4 expression in LUAD (r≥0.3). Among these transcription factors, TFAP2A was found to be aberrantly up-regulated in LUAD and exhibited the strongest correlation with ITGB4 expression (Figure 8B,8C). Moreover, high expression of TFAP2A was associated with poorer prognosis according to the TCGA database (Figure 8D). Knockdown of TFAP2A resulted in a significant reduction in ITGB4 expression, while overexpression of TFAP2A increased ITGB4 expression (Figure 8E,8F). Further investigation revealed that the binding site of TFAP2A in the ITGB4 promoter was located within the region spanning −235 to −222 bp. To validate this, we utilized PCR-mediated mutagenesis to remove the TFAP2A-binding motif from the ITGB4 promoter vector, resulting in a modified construct referred to as ITGB4-MUT. The original, unmodified construct was denoted as ITGB4-WT (Figure 8G). Furthermore, it was observed that TFAP2A overexpression significantly enhanced luciferase activity in the ITGB4-WT group, whereas TFAP2A knockdown resulted in a decrease in luciferase activity. Importantly, the luciferase activity of the ITGB4-MUT group remained unaffected by TFAP2A modulation (Figure 8H). ChIP assay also revealed that DNA fragments containing the putative TFAP2A-binding site were enriched in the chromatin immunoprecipitated by the anti-TFAP2A antibody compared with the control (anti-IgG) (Figure 8I). These findings indicated that TFAP2A could activate ITGB4 transcription by directly binding to the ITGB4 promoter in LUAD cells. The schematic diagram of this study was shown in Figure 8J.

Discussion

Immune-related genes play a crucial role in regulating tumor progression and immune responses in various types of malignant tumors, including LUAD. For instance, the immune-related gene FSCN1 is associated with the infiltration of CD4+ T cells, thereby promoting the development of LUAD (26). DFNA5 could regulate T cell exhaustion and influence the prognosis of patients with LUAD (27). Consistent with previous findings, the present study has unveiled a novel immune-associated gene, ITGB4, which could promote LUAD progression and inhibit CD4+/CD8+ T-cell infiltrations.

ITGB4, a crucial member of the integrin family, plays a critical role in cell migration, adhesion and differentiation in cancers (22,28,29). Upregulation of ITGB4 has been observed in various malignant tumors, including glioma, gastric and cervical cancer (30-32). In lung cancer, aberrant ITGB4 expression is associated with decreased overall survival (23,33). Activation of ITGB4 signaling by KCNF1 has been reported to be involved in accelerating the progression of lung cancer (34). However, the specific functions and underlying mechanisms of ITGB4 in LUAD progression are yet to be fully elucidated. Consistent with previous findings, the present study revealed that patients with higher ITGB4 expression had a worse prognosis. Moreover, functional assays indicated that ITGB4 could promote LUAD progression in vitro and in vivo.

Previous studies have shown that IκBα could limit p65 transportation into the nucleus and block NF-κB signaling. However, upon phosphorylation by the activated IκB kinase complex, IκBα is degraded, resulting in the activation of NF-κB (24, 25). Indeed, activation of the NF-κB signaling has been extensively reported to promote the progression of lung cancer (35-37). Consistent with these observations, our study revealed that ITGB4 could activate the NF-κB signaling through interacting with IκBα in LUAD. Moreover, functional assays indicated that NF-κB signaling may participate in the migratory phenotype induced by ITGB4. However, the precise interaction between ITGB4 and IκBα, including the specific binding domain, remains unclear. This represents a limitation in our current research, and we intend to conduct further exploration in future studies. Additionally, it is noteworthy that ITGB4 could serve as a cell surface receptor for various ligands. Among them, laminin-5 has been identified as a structural ligand that binds to ITGB4, thereby promoting tumor migration and invasion (38,39). Indeed, our results also suggested that laminin-5 could promote LUAD progression by activating the ITGB4 signaling.

The NF-κB signaling pathway plays a crucial role in mediating T-cell immune responses and influencing CD4+/CD8+ T-cell infiltration (40,41). Notably, IκBα could also promote CD8+ T-cell immunity in tumors (42). In our study, we discovered a negative correlation between ITGB4 expression and the infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in LUAD. This finding is consistent with previous studies reporting the involvement of ITGB4 in immune responses. For example, Tang et al. demonstrated that deficiency in airway epithelial ITGB4 in early life enhanced allergic immune responses (21). In LUAD, ITGB4 was reported to be positively associated with the infiltration of CD4+ T cells. Moreover, ITGB4 may affect immune cell infiltration through influencing immunomodulation-related genes (33). Indeed, increased infiltrations of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes were correlated with improved prognosis in patients with LUAD (43,44). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that ITGB4 might inhibit CD4+/CD8+ T-cell infiltrations through suppressing IκBα expression to activate the NF-κB signaling. However, the specific mechanism requires further in-depth research in the future.

In the current study, a significant suppression of LUAD cell tumorigenesis and metastasis in vivo was observed following ITGB4 knockdown. Remarkably, Ruan et al. indicated that ITGB4-targeted immunotherapies could effectively suppress tumor growth and reduce metastasis in various malignancies. Notably, the efficacy of ITGB4-targeted immunotherapies is significantly enhanced when combined with anti-PD-L1 treatment (45). PD-L1 can directly bind to ITGB4 to facilitate tumor progression and is able to hinder antitumor immunity by diminishing the infiltration of T lymphocytes, particularly CD8+ T cells (32,46,47). These findings suggested that ITGB4 might have potential to influence the outcomes of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapies and serve as a novel immunotherapeutic target for the treatment of LUAD. However, a limitation of our study is that we did not experimentally investigate the specific impact of ITGB4 in lung adenocarcinoma on anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapies, which is a focus of our future research efforts.

Our study revealed that TFAP2A can activate ITGB4 transcription in LUAD by directly binding to the ITGB4 promoter. The association between TFAP2A and ITGB4 expression has also been reported in pancreatic and colorectal cancer, although these findings have not been validated by functional assays (48,49). Importantly, TFAP2A has been implicated in promoting tumor progression in LUAD through the transcriptional regulation of other oncogenes. For instance, TFAP2A transcriptionally activates PSG9, leading to accelerated tumor progression in LUAD (50). Additionally, TFAP2A facilitates LUAD metastasis by positively regulating the transcription of ITPKA (51). Furthermore, significant bioinformatics research has uncovered similar biomarkers that could complement the present findings in this study. For instance, investigators have identified FEN1 as a facilitator of hepatocellular carcinoma progression through the enhancement of USP7/MDM2-mediated P53 inactivation (52). Additionally, researchers have demonstrated the chaperone function of HSP90-CDC37 in the oncogenic FGFR3-TACC3 fusion (53). These studies provide robust support for our findings.

Conclusions

ITGB4 was transcriptionally activated by TFAP2A, and could promote LUAD progression and suppress CD4+/CD8+ T-cell infiltrations by targeting the NF-κB signaling pathway. Therefore, ITGB4 may be a potential novel prognostic biomarker and a promising immunotherapeutic target for LUAD.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants and research staff for their contributions to this study.

Funding: This work was supported by

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the MDAR reporting checklist. Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-50/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-50/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-50/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-50/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants. All the procedures involving patient samples were compliant with all relevant ethical regulations and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Approval No. 2019-SR-123). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). And all animal experiments were performed under a project license (Approval No. IACUC-2208008) granted by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University, in compliance with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University for the care and use of animals.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Akerley W, et al. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 6.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2015;13:515-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang L, He YT, Dong S, et al. Single-cell transcriptome analysis revealed a suppressive tumor immune microenvironment in EGFR mutant lung adenocarcinoma. J Immunother Cancer 2022;10:e003534. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zavitsanou AM, Pillai R, Hao Y, et al. KEAP1 mutation in lung adenocarcinoma promotes immune evasion and immunotherapy resistance. Cell Rep 2023;42:113295. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Remark R, Becker C, Gomez JE, et al. The non-small cell lung cancer immune contexture. A major determinant of tumor characteristics and patient outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:377-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lambrechts D, Wauters E, Boeckx B, et al. Phenotype molding of stromal cells in the lung tumor microenvironment. Nat Med 2018;24:1277-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thommen DS, Koelzer VH, Herzig P, et al. A transcriptionally and functionally distinct PD-1(+) CD8(+) T cell pool with predictive potential in non-small-cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 blockade. Nat Med 2018;24:994-1004. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson SK, Kerr KM, Chapman AD, et al. Immune cell infiltrates and prognosis in primary carcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer 2000;27:27-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hiraoka K, Miyamoto M, Cho Y, et al. Concurrent infiltration by CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells is a favourable prognostic factor in non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2006;94:275-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruffini E, Asioli S, Filosso PL, et al. Clinical significance of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in lung neoplasms. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;87:365-71; discussion 371-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kawai O, Ishii G, Kubota K, et al. Predominant infiltration of macrophages and CD8(+) T Cells in cancer nests is a significant predictor of survival in stage IV nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer 2008;113:1387-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goc J, Germain C, Vo-Bourgais TK, et al. Dendritic cells in tumor-associated tertiary lymphoid structures signal a Th1 cytotoxic immune contexture and license the positive prognostic value of infiltrating CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res 2014;74:705-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita F, Tagawa T, Akamine T, et al. Interleukin-38 promotes tumor growth through regulation of CD8(+) tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in lung cancer tumor microenvironment. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2021;70:123-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor Mutational Burden and Response Rate to PD-1 Inhibition. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2500-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schoenfeld AJ, Arbour KC, Rizvi H, et al. Severe immune-related adverse events are common with sequential PD-(L)1 blockade and osimertinib. Ann Oncol 2019;30:839-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cesano A. nCounter(®) PanCancer Immune Profiling Panel (NanoString Technologies, Inc., Seattle, WA). J Immunother Cancer 2015;3:42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu F, Zhao Y, Pang Y, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome upregulates PD-L1 expression and contributes to immune suppression in lymphoma. Cancer Lett 2021;497:178-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma S, Cheng Q, Cai Y, et al. IL-17A produced by γδ T cells promotes tumor growth in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2014;74:1969-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tosti N, Cremonesi E, Governa V, et al. Infiltration by IL22-Producing T Cells Promotes Neutrophil Recruitment and Predicts Favorable Clinical Outcome in Human Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2020;8:1452-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jiao X, Sherman BT. DAVID-WS: a stateful web service to facilitate gene/protein list analysis. Bioinformatics 2012;28:1805-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang S, Du X, Yuan L, et al. Airway epithelial ITGB4 deficiency in early life mediates pulmonary spontaneous inflammation and enhanced allergic immune response. J Cell Mol Med 2020;24:2761-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuan L, Du X, Tang S, et al. ITGB4 deficiency induces senescence of airway epithelial cells through p53 activation. FEBS J 2019;286:1191-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen Z, Yang X, Bi G, et al. Ligand-receptor interaction atlas within and between tumor cells and T cells in lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Biol Sci 2020;16:2205-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang L, Zhang K, Zhang J, et al. Loss of fragile site-associated tumor suppressor promotes antitumor immunity via macrophage polarization. Nat Commun 2021;12:4300. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ji J, Ding K, Luo T, et al. TRIM22 activates NF-κB signaling in glioblastoma by accelerating the degradation of IκBα. Cell Death Differ 2021;28:367-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shi Y, Xu Y, Xu Z, et al. TKI resistant-based prognostic immune related gene signature in LUAD, in which FSCN1 contributes to tumor progression. Cancer Lett 2022;532:215583. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu J, Pei W, Jiang M, et al. DFNA5 regulates immune cells infiltration and exhaustion. Cancer Cell Int 2022;22:107. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sung JS, Kang CW, Kang S, et al. ITGB4-mediated metabolic reprogramming of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Oncogene 2020;39:664-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han L, Wang L, Tang S, et al. ITGB4 deficiency in bronchial epithelial cells directs airway inflammation and bipolar disorder-related behavior. J Neuroinflammation 2018;15:246. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hong D, Zhang X, Li R, et al. Deletion of TMEM268 inhibits growth of gastric cancer cells by downregulating the ITGB4 signaling pathway. Cell Death Differ 2019;26:1453-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma B, Zhang L, Zou Y, et al. Reciprocal regulation of integrin β4 and KLF4 promotes gliomagenesis through maintaining cancer stem cell traits. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2019;38:23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang S, Li J, Xie J, et al. Programmed death ligand 1 promotes lymph node metastasis and glucose metabolism in cervical cancer by activating integrin β4/SNAI1/SIRT3 signaling pathway. Oncogene 2018;37:4164-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu J, Wang W, Li Z, et al. The prognostic and immune infiltration role of ITGB superfamily members in non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Transl Res 2022;14:6445-66. [PubMed]

- Chen CY, Wu PY, Van Scoyk M, et al. KCNF1 promotes lung cancer by modulating ITGB4 expression. Cancer Gene Ther 2023;30:414-23. [PubMed]

- El-Nikhely N, Karger A, Sarode P, et al. Metastasis-Associated Protein 2 Represses NF-κB to Reduce Lung Tumor Growth and Inflammation. Cancer Res 2020;80:4199-211. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ren Y, Cao L, Wang L, et al. Autophagic secretion of HMGB1 from cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes metastatic potential of non-small cell lung cancer cells via NFκB signaling. Cell Death Dis 2021;12:858. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dimitrakopoulos FD, Kottorou AE, Kalofonou M, et al. The Fire Within: NF-κB Involvement in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res 2020;80:4025-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rousselle P, Scoazec JY. Laminin 332 in cancer: When the extracellular matrix turns signals from cell anchorage to cell movement. Semin Cancer Biol 2020;62:149-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schinke H, Shi E, Lin Z, et al. A transcriptomic map of EGFR-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition identifies prognostic and therapeutic targets for head and neck cancer. Mol Cancer 2022;21:178. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hopewell EL, Zhao W, Fulp WJ, et al. Lung tumor NF-κB signaling promotes T cell-mediated immune surveillance. J Clin Invest 2013;123:2509-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li L, Han L, Sun F, et al. NF-κB RelA renders tumor-associated macrophages resistant to and capable of directly suppressing CD8(+) T cells for tumor promotion. Oncoimmunology 2018;7:e1435250. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lisiero DN, Cheng Z, Tejera MM, et al. IκBα Nuclear Export Enables 4-1BB-Induced cRel Activation and IL-2 Production to Promote CD8 T Cell Immunity. J Immunol 2020;205:1540-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peng H, Wu X, Zhong R, et al. Profiling Tumor Immune Microenvironment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Using Multiplex Immunofluorescence. Front Immunol 2021;12:750046. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edlund K, Madjar K, Mattsson JSM, et al. Prognostic Impact of Tumor Cell Programmed Death Ligand 1 Expression and Immune Cell Infiltration in NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:628-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruan S, Lin M, Zhu Y, et al. Integrin β4-Targeted Cancer Immunotherapies Inhibit Tumor Growth and Decrease Metastasis. Cancer Res 2020;80:771-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Juneja VR, McGuire KA, Manguso RT, et al. PD-L1 on tumor cells is sufficient for immune evasion in immunogenic tumors and inhibits CD8 T cell cytotoxicity. J Exp Med 2017;214:895-904. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peng Q, Qiu X, Zhang Z, et al. PD-L1 on dendritic cells attenuates T cell activation and regulates response to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Commun 2020;11:4835. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhuang H, Zhou Z, Ma Z, et al. Characterization of the prognostic and oncologic values of ITGB superfamily members in pancreatic cancer. J Cell Mol Med 2020;24:13481-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mao X, Zhang X, Zheng X, et al. Curcumin suppresses LGR5(+) colorectal cancer stem cells by inducing autophagy and via repressing TFAP2A-mediated ECM pathway. J Nat Med 2021;75:590-601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiong Y, Feng Y, Zhao J, et al. TFAP2A potentiates lung adenocarcinoma metastasis by a novel miR-16 family/TFAP2A/PSG9/TGF-β signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis 2021;12:352. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guoren Z, Zhaohui F, Wei Z, et al. TFAP2A Induced ITPKA Serves as an Oncogene and Interacts with DBN1 in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Int J Biol Sci 2020;16:504-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bian S, Ni W, Zhu M, et al. Flap endonuclease 1 Facilitated Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression by Enhancing USP7/MDM2-mediated P53 Inactivation. Int J Biol Sci 2022;18:1022-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li T, Mehraein-Ghomi F, Forbes ME, et al. HSP90-CDC37 functions as a chaperone for the oncogenic FGFR3-TACC3 fusion. Mol Ther 2022;30:1610-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]