Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting visceral pleural invasion in patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer

Highlight box

Key findings

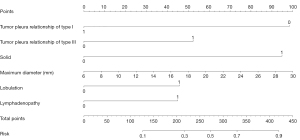

• The nomogram combining tumor pleura relationship of type I and type III, solid, maximum diameter, lobulation, and lymphadenopathy achieved good performance in predicting visceral pleural invasion (VPI) preoperatively with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

What is known and what is new?

• VPI has been recognized as an important indicator affecting the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging of tumors in early-stage NSCLC. Some computed tomography (CT) features had already been related to VPI.

• In this study, the nomogram combining CT features was constructed and performed well in predicting VPI with early-stage NSCLC.

What is the implication, and what is should change now?

• The nomogram combining CT features could be implemented in predicting VPI preoperatively and facilitate the selection of surgical methods. Further prospective multi-institutional studies should be designed to validate the value of these findings.

Introduction

As the most prevalent type of malignant tumor, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death (1). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common form of lung cancer (2). Surgery is the main treatment for early-stage NSCLC. Visceral pleural invasion (VPI) has been identified as a predictor of a poor prognosis in NSCLC (3). In the eighth tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system, if VPI is detected, tumors 3 cm or less in diameter will be upgraded from T1 to T2a (4), which could affect the planning of surgical resection and postoperative adjuvant therapy. In early-stage NSCLC with VPI, lobectomy is a more desirable surgical approach as it leads to better survival and prognosis than sublobar resection (5). However, identifying the presence of VPI through preoperative puncture biopsy or intraoperative macroscopic observations is challenging. Therefore, the accurate prediction of VPI in early-stage NSCLC via imaging has significance.

Computed tomography (CT) is the preferred radiological examination method for NSCLC. A few studies have shown that specific CT features are predictive of VPI (6-8). These studies mainly focused on the different CT features in solid and subsolid nodules, the accuracy of different pleural tags for VPI diagnosis, or the arch distance-to-maximum tumor diameter ratios of larger T3 and T4 NSCLCs. However, their diagnostic efficacy has been limited and variable. The predictive performance of VPI using preoperative CT features in early-stage NSCLC still needs improvement.

Nomograms can integrate predictive factors to establish a statistical model and contribute to clinical decision-making. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to establish a nomogram model based on CT morphological characteristics to predict VPI in early-stage NSCLC for facilitating the selection of surgical planning. We present this article in accordance with the TRIPOD reporting checklist (available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-459/rc).

Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Wuhan Union Hospital (Wuhan, China) (No. S254), and the requirement for individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Patients and inclusion criteria

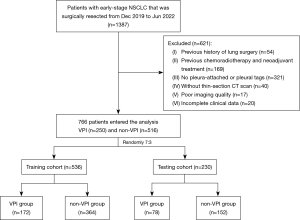

A total of 766 early-stage NSCLC patients were retrospectively collected from December 2019 to June 2022 at the Union Hospital of Tongji Medical College. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) NSCLC pathologically confirmed by surgical resection; (II) the presence of VPI had been assessed by specific elastic staining; (III) tumors were 3 cm or less in maximum diameter on preoperative CT scan; and (IV) patients underwent surgery within one month after CT scans. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) patients who had undergone previous lung surgery (n=54); (II) previous chemoradiotherapy and neoadjuvant treatment (n=169); (III) without pleura-attached or pleural tags (n=321); (IV) without thin-section CT before treatment (n=40); (V) poor imaging quality due to respiratory or movement artifacts (n=17); and (VI) clinical data could not be found or incomplete (n=20). The eligible NSCLC patients were randomly divided into a training cohort (n=536) and a testing cohort (n=230) at a ratio of 7:3 (Figure 1). Clinical demographic characteristics such as age, gender, and smoking history were examined.

CT image acquisition

CT examinations were performed at our hospital using one of two CT systems (SOMATOM Definition AS+, Siemens Healthineers, Forchheim, Germany; Toshiba Aquilion One, Nasu, Japan). The CT parameters were as follows: detector collimation widths, 64×0.6 mm and 128×0.6 mm; tube voltage, 120 kV. The tube current was regulated by an automatic exposure control system (CARE Dose 4D). All examinations were performed over the entire thorax with the patient in the supine position and at full inspiration. Images were reconstructed in transverse, sagittal, and coronal planes, with a slice thickness of 1.5 mm and an interval of 1.5 mm. The lung window level was −600 Hounsfield units (HU), and the width was 1,600 HU; the mediastinal window level was 50 HU, and the width was 350 HU.

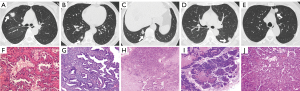

CT image interpretation

Two experienced radiologists (T.G., a radiologist with 10 years of CT image interpretation expertise, and H.S., a thoracic radiologist with 35 years of expertise) independently assessed all imaging data. Both radiologists who analyzed the CT images were blinded to the clinical information and pathology results. CT features included tumor pleura relationships and other CT features. According to the previous studies (7,9,10), we divided the tumor pleura relationship into five types (Figure 2): type I, one or more linear pleural tags; type II, one or more linear pleural tags with soft tissue components at the pleural end; type III, one or more bold-wire pleural tags with soft tissue components at the pleural end; type IV, tumor was attached to the pleura without pleural abnormality; and type V, tumor was in direct contact with pleura and pleural distortion. Other CT features included the following: tumor location (right upper lobe, right middle lobe, right lower lobe, left upper lobe, or left lower lobe), maximum tumor diameter on the lung window, tumor density [pure ground-glass opacity (pGGO), mixed GGO (mGGO), or solid], spiculation, lobulation, lymphadenopathy, cavity, calcification, involved pleura (non-interlobar fissure pleura, interlobar fissure pleura, or both), presence of solid portion in contact with the pleura, pleural thickening, and pleural effusion. Any disagreements between the radiologists were settled through discussion. In addition, for the assessment of inter-reader agreement, two radiologists (T.G. and H.S.) individually reviewed 50 randomly selected CT images to evaluate tumor CT features and recorded the results.

Pathologic assessment

All specimens were evaluated by two experienced pathologists (J.F. and N.W., with 6 and 12 years of experience in thoracic pathology, respectively). Specific elastic staining of the involved pleura of all resected tumors was performed to confirm the presence or absence of pleural tumor invasion and its extent. When tumor tissue breaks through the elastic layer and invades the visceral pleural surface, it is indicative of VPI (11).

Statistical analysis

We used the software SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R software (version 4.3.3, available at http://www.rproject.org/) to analyze the data in this research. After testing for skewed distribution, continuous variables were represented as median with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were represented by frequency and percentage. To compare continuous variables between the VPI and non-VPI groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed, whereas the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was utilized to examine categorical variables between groups. For inter-reader agreement, kappa values were interpreted as follows: <0.4, poor agreement; 0.4–0.75, substantial agreement; >0.75, almost perfect agreement. The training cohort was used to develop the prediction model, and the testing cohort was used to validate the performance of the model. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to identify the risk factors in VPI patients, and a nomogram was built based on the results of the multivariate analysis. We assessed the performance of the model in predicting VPI using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The ‘rms’, ‘pROC’, and ‘nomogramFormula’ packages were applied to perform the nomogram and ROC curve analysis. Calibration plots were used to estimate the overall agreement between the predicted and observed incidence of VPI. We used decision curve analysis (DCA) to evaluate the clinical utility of the nomogram. A P value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant in all analyses.

Results

Correlation of VPI with clinicopathologic characteristics

The clinicopathologic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Data from 766 patients were analyzed; VPI was confirmed in 32.6% (250 of 766) of patients. In the training cohort, the median age of this study population was 59 years (age range, 25–81 years), and it included 316 women (median age, 58 years; age range, 25–80 years) and 220 men (median age, 61 years; age range, 33–81 years). More patients who had VPI (157 of 172, 91.3%) underwent lobectomy than did patients who did not have VPI (283 of 364, 77.7%) (P<0.001). No significant differences were found between VPI and non-VPI cases in smoking history (P=0.34) or pathological type (P=0.84).

Table 1

| Characteristics | Training cohort | Testing cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPI (+) (n=172) | VPI (−) (n=364) | P value | VPI (+) (n=78) | VPI (−) (n=152) | P value | ||

| Gender, n (%) | <0.001* | 0.54 | |||||

| Female | 86 (50.0) | 230 (63.2) | 38 (48.7) | 82 (53.9) | |||

| Male | 86 (50.0) | 134 (36.8) | 40 (51.3) | 70 (46.1) | |||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 61 (55, 67) | 59 (52, 66) | 0.01* | 59 (53, 67) | 60 (52, 66) | 0.56 | |

| Smoke, n (%) | 0.34 | 0.43 | |||||

| Never | 128 (74.4) | 286 (78.6) | 60 (76.9) | 125 (82.2) | |||

| Former or current | 44 (25.6) | 78 (21.4) | 18 (23.1) | 27 (17.8) | |||

| Surgery types, n (%) | <0.001* | <0.001* | |||||

| Wedge resection | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | |||

| Segmentectomy | 13 (7.5) | 81 (22.3) | 6 (7.7) | 41 (27.0) | |||

| Lobectomy | 157 (91.3) | 283 (77.7) | 71 (91.0) | 110 (72.4) | |||

| Pathological types, n (%) | 0.84 | 0.14 | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 166 (96.5) | 354 (97.3) | 75 (96.2) | 146 (96.1) | |||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 2 (1.2) | 4 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.6) | |||

| Others | 4 (2.3) | 6 (1.6) | 3 (3.8) | 2 (1.3) | |||

*, P<0.05. VPI, visceral pleural invasion; IQR, interquartile range.

Correlation of VPI with CT features

CT features correlated with VPI in the training cohort are summarized in Table 2. No relationship was found between VPI and tumor location (P=0.62). Compared with patients of non-VPI, the maximum diameter of tumor tended to be larger in patients with VPI (21 vs. 18 mm, P<0.001). Tumor densities differed between the VPI and non-VPI groups (P<0.001). The majority of VPI tumors manifested as solid nodules (126/172, 73.3%), followed by the mGGOs (43/172, 25.0%) and pGGOs (3/172, 1.7%). A statistically significant difference was noted between VPI and the types of tumor pleura relationship (P<0.001): tumor pleura relationship of type III was higher in VPI group than in non-VPI group, whereas type I was lower in VPI group than in non-VPI group. Moreover, VPI was associated with spiculation, lobulation, lymphadenopathy, involved pleura, presence of solid portion in contact with the pleura, and pleural thickening (all P<0.001). No differences were found among other CT features (P>0.05).

Table 2

| Variables | Training cohort | Testing cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPI (+) (n=172) | VPI (−) (n=364) | P value | VPI (+) (n=78) | VPI (−) (n=152) | P value | ||

| Tumor location, n (%) | 0.62 | 0.38 | |||||

| Right upper lobe | 67 (39.0) | 120 (33.0) | 21 (26.9) | 49 (32.2) | |||

| Right middle lobe | 12 (7.0) | 28 (7.7) | 12 (15.4) | 13 (8.6) | |||

| Right lower lobe | 32 (18.6) | 81 (22.3) | 17 (21.8) | 32 (21.1) | |||

| Left upper lobe | 40 (23.3) | 81 (22.3) | 13 (16.7) | 35 (23.0) | |||

| Left lower lobe | 21 (12.2) | 54 (14.8) | 15 (19.2) | 23 (15.1) | |||

| Maximum diameter (mm), median (IQR) | 21 (17, 25) | 18 (13, 22) | <0.001* | 22 (19, 25) | 18 (13, 22) | <0.001* | |

| Density, n (%) | <0.001* | <0.001* | |||||

| pGGO | 3 (1.7) | 53 (14.6) | 1 (1.3) | 27 (17.8) | |||

| mGGO | 43 (25.0) | 219 (60.2) | 19 (24.4) | 86 (56.6) | |||

| Solid | 126 (73.3) | 92 (25.3) | 58 (74.4) | 39 (25.7) | |||

| Spiculation, n (%) | <0.001* | <0.001* | |||||

| Absence | 65 (37.8) | 205 (56.3) | 17 (21.8) | 82 (53.9) | |||

| Prescence | 107 (62.2) | 159 (43.7) | 61 (78.2) | 70 (46.1) | |||

| Lobulation, n (%) | <0.001* | <0.001* | |||||

| Absence | 73 (42.4) | 286 (78.6) | 38 (48.7) | 115 (75.7) | |||

| Prescence | 99 (57.6) | 78 (21.4) | 40 (51.3) | 37 (24.3) | |||

| Lymphadenopathy, n (%) | <0.001* | 0.15 | |||||

| Absence | 137 (79.7) | 334 (91.8) | 67 (85.9) | 141 (92.8) | |||

| Prescence | 35 (20.3) | 30 (8.2) | 11 (14.1) | 11 (7.2) | |||

| Cavity, n (%) | >0.99 | 0.40 | |||||

| Absence | 158 (91.9) | 333 (91.5) | 69 (88.5) | 141 (92.8) | |||

| Prescence | 14 (8.1) | 31 (8.5) | 9 (11.5) | 11 (7.2) | |||

| Calcification, n (%) | 0.78 | 0.61 | |||||

| Absence | 167 (97.1) | 355 (97.5) | 76 (97.4) | 150 (98.7) | |||

| Prescence | 5 (2.9) | 9 (2.5) | 2 (2.6) | 2 (1.3) | |||

| Tumor pleura relationship, n (%) | <0.001* | 0.04* | |||||

| Type I | 6 (3.5) | 58 (15.9) | 6 (7.7) | 30 (19.7) | |||

| Type II | 25 (14.5) | 52 (14.3) | 15 (19.2) | 27 (17.8) | |||

| Type III | 35 (20.3) | 25 (6.9) | 11 (14.1) | 13 (8.6) | |||

| Type IV | 14 (8.1) | 40 (11.0) | 6 (7.7) | 22 (14.5) | |||

| Type V | 92 (53.5) | 189 (51.9) | 40 (51.3) | 60 (39.5) | |||

| Involved pleura, n (%) | <0.001* | 0.03* | |||||

| Non-interlobar fissure pleura | 111 (64.5) | 217 (59.6) | 48 (61.5) | 98 (64.5) | |||

| Interlobar fissure pleura | 20 (11.6) | 90 (24.7) | 9 (11.5) | 32 (21.1) | |||

| Both | 41 (23.8) | 57 (15.7) | 21 (26.9) | 22 (14.5) | |||

| Presence of solid portion in contact with the pleura, n (%) | <0.001* | <0.001* | |||||

| Absence | 58 (33.7) | 195 (53.6) | 31 (39.7) | 97 (63.8) | |||

| Prescence | 114 (66.3) | 169 (46.4) | 47 (60.3) | 55 (36.2) | |||

| Pleural thickening | <0.001* | <0.001* | |||||

| Absence | 73 (42.4) | 217 (59.6) | 28 (35.9) | 96 (63.2) | |||

| Prescence | 99 (57.6) | 147 (40.4) | 50 (64.1) | 56 (36.8) | |||

| Pleural effusion | 0.10 | >0.99 | |||||

| Absence | 170 (98.8) | 364 (100.0) | 78 (100.0) | 151 (99.3) | |||

| Prescence | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | |||

*, P<0.05. CT, computed tomography; VPI, visceral pleural invasion; pGGO, pure ground-glass opacity; mGGO, mix ground-glass opacity; IQR, interquartile range.

Interobserver agreement in CT interpretation

The intraclass correlation coefficient for tumor maximum diameter was 0.934 (95% CI: 0.887–0.962). The concordance between the two observers was good for other CT features, with k coefficients ranging between 0.696 and 0.959 (Table 3).

Table 3

| CT features | N/Ntotal | Kappa (95% CI) | Kappa interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | 45/50 | 0.831 (0.694–0.968) | Almost perfect |

| Spiculation | 44/50 | 0.758 (0.578–0.938) | Almost perfect |

| Lobulation | 46/50 | 0.838 (0.685–0.991) | Almost perfect |

| Lymphadenopathy | 46/50 | 0.752 (0.527–0.977) | Almost perfect |

| Cavity | 47/50 | 0.696 (0.378–1.000) | Substantial |

| Tumor pleura relationship | 44/50 | 0.814 (0.675–0.953) | Almost perfect |

| Involved pleura | 47/50 | 0.882 (0.759–1.000) | Almost perfect |

| Presence of solid portion in contact with the pleura | 49/50 | 0.959 (0.881–1.000) | Almost perfect |

| Pleural thickening | 46/50 | 0.840 (0.691–0.989) | Almost perfect |

CT, computed tomography; CI, confidence interval.

Development and validation of the VPI prediction nomogram

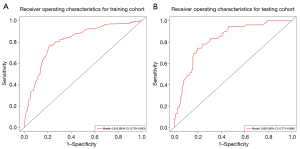

The multivariable logistic regression analysis included variables with P<0.05 from the univariable analysis. The tumor pleura relationship of type I, tumor pleura relationship of type III, density of solid, maximum diameter, lobulation, and lymphadenopathy were found to be independent risk predictors for predicting VPI in early-stage NSCLC, according to the results from the multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 4). A nomogram was constructed based on the best combination of the six predictive factors above to provide a visualized outcome measure in Figure 3. The nomogram showed good discrimination, with areas under the ROC curves (AUCs) of 0.815 (95% CI: 0.776–0.853) and 0.825 (95% CI: 0.771–0.880) in the training and testing cohorts, respectively (Figure 4). Meanwhile, the sensitivities of the model for predicting VPI in the training and testing cohorts are 76.7% and 74.5%, respectively, with specificities of 78.8% and 80.3%, respectively.

Table 4

| VPI | Coef. | St.err. | z value | P value | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.9954 | 0.4332 | −6.91 | <0.001 | *** |

| Tumor pleura relationship of type I | −1.4719 | 0.4793 | −3.07 | 0.002 | ** |

| Tumor pleura relationship of type III | 0.7829 | 0.3226 | 2.43 | 0.02 | * |

| Solid | 1.4201 | 0.2532 | 5.61 | <0.001 | *** |

| Maximum diameter | 0.0624 | 0.0209 | 2.98 | 0.003 | ** |

| Lobulation | 0.6842 | 0.2543 | 2.69 | 0.007 | ** |

| Lymphadenopathy | 0.6721 | 0.3126 | 2.15 | 0.03 | * |

| Akaike crit. (AIC) | 531.7 |

*, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. VPI, visceral pleural invasion; Coef., coefficient; St., standard; err., error; Sig., significant.

Calibration analysis and clinical use

By observing the calibration curve, the actual results of VPI were highly consistent with the predicted results of VPI, and the testing cohort was consistent with the training cohort (Figure 5). The concordance index (C-index) of the nomogram for VPI prediction was 0.815. In addition, DCA showed that the nomogram model is effective in clinical practice (Figure 6).

Discussion

VPI is associated with an increased risk of lymph node metastasis and, thus, the choice of surgical procedure will affect prognosis (5,12). Preoperative prediction of VPI can provide a more accurate clinical basis for treatment decisions. In our study, the frequency of VPI was 32.6% in the surgically resected early-stage NSCLC specimens. We constructed and validated a nomogram model for VPI prediction in early-stage NSCLC with tumor pleura relationships of type I and type III, solid, maximum diameter, lobulation, and lymphadenopathy. The nomogram model effectively classified early-stage NSCLC patients into those who had VPI and those who did not, with AUCs of 0.815 and 0.825 in the training cohort and the testing cohort, respectively. It is worth noting that our study focused on the visceral pleura invasion, and T3 in which parietal pleural invasion occurred was not included in this study.

According to the involved pleural morphological changes, types I–III in this study are different forms of pleural tags. Type I pleural tag means one or more linear strands; type II pleural tag means one or more linear strands with a soft-tissue component at the end of the pleura; and type III pleural tag means one or more soft-tissue cord-like strands (7). The pathologies of pleural tags are localized edema, tumor infiltration through lymphatic vessels or beyond, inflammatory infiltrates, or fibrotic changes (7). Our work demonstrated that in early-stage NSCLC, the tumor pleura relationships of type I and type III were independent risk factors for VPI. Similar to previous findings (7,10,13), the presence of tumor pleura relationship of type I could not increase the risk probability of VPI occurrence. This condition prefers thickening of the interlobular septa due to inflammatory cells or fibrosis associated with benign lesions (10). The tumor pleura relationship of type III exhibits thickening and opacity, possibly suggesting infiltration by tumor cells and obstruction leading to lymphatic edema, while the proliferative fibrous tissue contracts and pulls the pleura, thereby contributing to the development of VPI (10,13).

Tumor density is associated with the invasiveness of NSCLC. Among the morphological features evaluated in our study, regarding the density of tumors, only four pGGOs experienced VPI, and the possibility of VPI was highest in solid nodules (184 of 250; 73.6%). This is consistent with earlier findings (9,14,15). Furthermore, it has been determined that the presence of a solid component is an indication of invasive lesions in pulmonary nodules (16,17), as well as that the malignancy of the lesion positively relates with the proportion of the solid component (18). In univariate analysis, our study showed a statistical difference in the presence of solid portion in contact with the pleura between the VPI and non-VPI groups (P<0.01). However, it was not identified as an independent risk factor for VPI in early-stage NSCLC in multivariate analysis.

Earlier research on CT findings related to pleural invasion has demonstrated the utility of tumor size as a significant feature, independently associated with VPI (19). Compared to the VPI patients, the diameter of non-VPI patients was smaller (P<0.01), similar to Heidinger et al.’s and Deng et al.’s studies (6,20). In our study, lobulation was also shown to be predictive of VPI. This aligns with findings demonstrating that lobulated contours have a positive correlation with the rate of cell growth and, thus, with malignancy (21).

Our research indicates that lymphadenopathy observed on CT scans is a risk factor for VPI in early-stage NSCLC, consistent with findings from prior studies (22). The pleura is densely populated with interconnected lymphatic vessels that drain into the mediastinal lymph nodes (22), so tumor cells can invade and metastasize to mediastinal lymph nodes through VPI. Previous investigation has shown that lymphadenopathy on CT is a hazard for metastasis in solid lung cancer (23). Therefore, lymphadenopathy on CT scans indicates a likelihood of VPI.

Our present nomogram demonstrated exceptional predictive value in both the training and testing cohorts (AUC 0.815 and 0.825, respectively). Zuo et al. constructed a nomogram containing texture features to predict the VPI of lung adenocarcinoma (24). Zha et al. constructed a nomogram combining radiomics and CT features for the VPI prediction of lung adenocarcinoma (25). Cai et al. predicted VPI of solid lung adenocarcinoma by developing a nomogram combining higher-order radiomics features, tumor pleural relationships, and lymph node enlargement (9). Their models exhibited high classification properties, with AUCs of 0.890, 0.890, and 0.877, which are slightly higher than ours. Some possible reasons for the above differences could be that we chose tumors of all densities rather than selection two of them for comparison, and that radiomics features were not considered.

Some limitations of our study should be mentioned. First, as a retrospective study with a single institution, patient selection bias was inevitable, and there was a lack of external validation of the model. Second, we only focused on whether the tumor was in contact with the interlobular pleura, without further classifying pleural tumors in different locations. Due to the different composition of the pleura in different locations, this may have led to bias in our results. Finally, different degrees of VPI have different impacts on patient prognosis, but we did not differentiate the degree of pleural invasion. Further prospective, multi-institutional studies are mandatory to validate the value of CT features in the diagnosis of VPI in early-stage NSCLC.

Conclusions

When predicting VPI, tumor pleura relationship of type I and type III, solid, maximum diameter, lobulation, and lymphadenopathy is important to consider. The CT-based morphological characteristics nomogram that we have established can serve as a vital reference for VPI prediction in early-stage NSCLC and may be used to guide clinical treatment decisions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the TRIPOD reporting checklist. Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-459/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-459/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-459/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-459/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Wuhan Union Hospital (Wuhan, China) (No. S254), and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74:229-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xia C, Dong X, Li H, et al. Cancer statistics in China and United States, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin Med J (Engl) 2022;135:584-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang H, Wang T, Hu B, et al. Visceral pleural invasion remains a size-independent prognostic factor in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;99:1130-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ, Kim AW, et al. The Eighth Edition Lung Cancer Stage Classification. Chest 2017;151:193-203.

- Huang W, Deng HY, Lin MY, et al. Treatment Modality for Stage IB Peripheral Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer With Visceral Pleural Invasion and ≤3 cm in Size. Front Oncol 2022;12:830470. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heidinger BH, Schwarz-Nemec U, Anderson KR, et al. Visceral Pleural Invasion in Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma: Differences in CT Patterns between Solid and Subsolid Cancers. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 2019;1:e190071. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hsu JS, Han IT, Tsai TH, et al. Pleural Tags on CT Scans to Predict Visceral Pleural Invasion of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer That Does Not Abut the Pleura. Radiology 2016;279:590-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Imai K, Minamiya Y, Ishiyama K, et al. Use of CT to evaluate pleural invasion in non-small cell lung cancer: measurement of the ratio of the interface between tumor and neighboring structures to maximum tumor diameter. Radiology 2013;267:619-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cai X, Wang P, Zhou H, et al. CT-based radiomics nomogram for predicting visceral pleural invasion in peripheral T1-sized solid lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Cancer Res 2023;13:5901-13. [PubMed]

- Meng Y, Gao J, Wu C, et al. The prognosis of different types of pleural tags based on radiologic-pathologic comparison. BMC Cancer 2022;22:919. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rami-Porta R, Bolejack V, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for the Revisions of the T Descriptors in the Forthcoming Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:990-1003.

- Yu Y, Huang R, Wang P, et al. Sublobectomy versus lobectomy for long-term survival outcomes of early-stage non-small cell lung cancer with a tumor size ≤2 cm accompanied by visceral pleural invasion: a SEER population-based study. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:592-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang S, Yang L, Teng L, et al. Visceral pleural invasion by pulmonary adenocarcinoma ≤3 cm: the pathological correlation with pleural signs on computed tomography. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:3992-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yip R, Ma T, Flores RM, et al. Survival with Parenchymal and Pleural Invasion of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers Less than 30 mm. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:890-902. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okada S, Hattori A, Matsunaga T, et al. Prognostic value of visceral pleural invasion in pure-solid and part-solid lung cancer patients. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021;69:303-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bai JH, Hsieh MS, Liao HC, et al. Prediction of pleural invasion using different imaging tools in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Transl Med 2019;7:33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fu F, Zhang Y, Wen Z, et al. Distinct Prognostic Factors in Patients with Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with Radiologic Part-Solid or Solid Lesions. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:2133-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mazzone PJ, Lam L. Evaluating the Patient With a Pulmonary Nodule: A Review. JAMA 2022;327:264-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahn SY, Park CM, Jeon YK, et al. Predictive CT Features of Visceral Pleural Invasion by T1-Sized Peripheral Pulmonary Adenocarcinomas Manifesting as Subsolid Nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2017;209:561-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deng HY, Li G, Luo J, et al. Novel biologic factors correlated to visceral pleural invasion in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer less than 3 cm. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:2357-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin X, Liu K, Li K, et al. A CT-based deep learning model: visceral pleural invasion and survival prediction in clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma. iScience 2024;27:108712. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iizuka S, Kawase A, Oiwa H, et al. A risk scoring system for predicting visceral pleural invasion in non-small lung cancer patients. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;67:876-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang B, Sun K, Meng X, et al. The Different Evaluative Significance of Enlarged Lymph Nodes on Preoperative CT in the N Stage for Patients with Suspected Subsolid and Solid Lung Cancers. Acad Radiol 2023;30:1392-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zuo Z, Li Y, Peng K, et al. CT texture analysis-based nomogram for the preoperative prediction of visceral pleural invasion in cT1N0M0 lung adenocarcinoma: an external validation cohort study. Clin Radiol 2022;77:e215-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zha X, Liu Y, Ping X, et al. A Nomogram Combined Radiomics and Clinical Features as Imaging Biomarkers for Prediction of Visceral Pleural Invasion in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol 2022;12:876264. [Crossref] [PubMed]