Lung cancer organoids: a new strategy for precision medicine research

Introduction

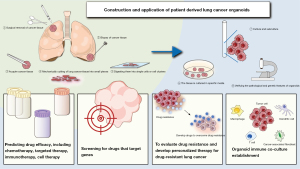

Precision medicine aims to identify and develop highly selective drugs targeting specific disease markers to achieve precise treatment. Due to the genetic heterogeneity of lung cancer cells, different tumor cells may respond differently to various therapeutic agents (1). The genetic heterogeneity of lung cancer is a key factor leading to acquired resistance (2), while intratumoral heterogeneity (ITH) is also a potential biomarker that can predict the efficacy of treatments in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients and other tumors receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) (3). Understanding tumor heterogeneity is fundamental to establishing the optimal precision treatment plan. Conventional two-dimensional (2D) cell lines, which are easy to obtain and culture, are widely used in basic research but fail to reflect tumor heterogeneity and the actual drug response of the parental tumor. In contrast, patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models from patients with lung cancer better preserve tumor heterogeneity. However, their use is limited by factors such as low success rates, high costs, and ethical issues (4), as well as some drawbacks common to animal models, including delayed implantation rates and interspecies differences (5). In particular, the differences in the immune system in mouse models make them inadequate for accurately replicating the complexity of the human immune microenvironment in cancer, leading to unsatisfactory predictions of the efficacy of immunotherapy (6). Organoid technology not only faithfully reproduces the pathological and genomic characteristics of samples (7,8), preserving most variations, including driver gene mutations (9), but also maintains the cytological features of malignant tumors (10), with in vitro drug screening responses highly correlated with the mutation spectrum in primary tumors (11). Most studies produce organoids from surgical resection samples or biopsy-derived samples (Figure 1). After cutting lung cancer tissue into small pieces and digesting them into single cells or cell clusters, the tissue is cultured in specific media, regularly observed and the medium is changed, and the organoids’ pathological and genetic characteristics are validated through staining and sequencing. Under this culture system, the genetic, proteomic, morphological, and pharmacological characteristics of tissue samples obtained from specific patients are largely retained in the in vitro cultured lung cancer organoids (LCOs) (12). Therefore, this novel system closely related to the original tumor provides valuable information for tumor biology, drug development, patient reactivity prediction, and clinical translation of high-throughput methods (13). This article focuses on the application of LCO models in basic research, including the discovery of drug targets, prediction of drug efficacy, and the development of new therapeutic strategies, which helps formulate personalized treatment strategies targeting specific tumor cell subpopulations to improve treatment outcomes. We also emphasize the potential value of cancer organoid co-culture models in immunotherapy and their positive impact on the study of precision medicine strategies.

Application of LCOs

The application of LCOs in the validation of tumor biomarkers

Organoids provide a distinct advantage over clinical lung cancer samples by delivering higher purity, thereby simplifying the exploration of tumor biomarkers. This is because the differences in gene expression between tumor cells and non-tumor cells in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) organoids are not influenced by stromal cells and immune cells (14). In LUAD organoid models, MEK has been identified as a promising target for LUADs with specific KRAS mutations (10). Glutathione S-transferase pi (GSTP1) has been shown to exert long-term control over LUAD by targeting cancer stem cells (CSCs) (15). Liu et al. generated patient-derived organoids (PDOs) from surgically resected LUAD specimens, confirming that elevated c-fos expression results in the upregulation of carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecule 6 (CEACAM6), thereby promoting tumor metastasis both in vitro and in vivo (16). Further research concluded the mechanism of LUAD metastasis induced by the BRMS1v2A273V/A273V mutation (16). Ample evidence has confirmed that the use of LCOs can facilitate the discovery of new therapeutic targets and accurately predict the therapeutic response by targeting these biomarkers. The expression status of NKX2-1 can predict responses to Wnt-targeted therapies (8). Inhibitors of another CSC marker, DCLK1, can reverse secondary resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitions (TKIs) in both tumor cells and organoids (17). Lysine methyltransferase 2D (KMT2D) has been identified as a pivotal epigenetic regulator in the onset of lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) (18). Han et al. found elevated CD73 (ecto-5'-nucleotidase) expression in organoids from NSCLC patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) mutations, suggesting CD73 as a possible therapeutic target for these cancers (19). Pharmacological inhibitors of fascin (a pro-metastatic actin-bundling protein) can inhibit YAP1-PFKFB3 signaling and glycolysis in organoid models, and can be used to reprogram lung cancer metabolism (20). Fascin inhibitors can suppress both tumor growth and its spread to other parts of the body (20). Tyc et al. identified a 30-gene signature, “KDS30”, which predicts the dependency on EGFR/ERBB2 (EGFR2) signaling, drug response, and survival in patients with mt KRAS mutations in lung and pancreatic cancers (21). In small cell lung cancer (SCLC) organoid models, the novel YES1 inhibitor CH6953755 or dasatinib induced significant antitumor activity, demonstrating that YES1 is a new druggable oncogenic target and biomarker (22). These methods that leverage LCOs to validate tumor biomarkers provide critical information and potential strategies for personalized treatment and the development of new drugs (Table 1).

Table 1

| LCOs based on subtypes | Organizational sources | Related drugs or targets | Main results in drug efficacy prediction/drug screening | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LUAD, LUSC | Sputum, CTCs | MEK inhibitors (trametinib and selumetinib), FGFR inhibitor (BGJ398) | KRAS-mutated organoids exhibit high sensitivity to trametinib and selumetinib. Organoids with FGFR1 amplification display resistance to BGJ398; organoids with FGFR1 amplification exhibit synergistic effects when used in combination with trametinib | (10) |

| LUAD | Derived from patients | GSTP1 inhibitor (ezatiostat), ALK inhibitor (crizotinib) | GSTP1 is a promising therapeutic target in LUAD treatment. GSTP1 might mediate TKI resistance by enhancing the CSC resilience of LUAD | (15) |

| LUAD | Derived from patients | The c-fos pharmacological inhibitor (T5224) | T5224 can inhibit metastasis in BRMS1v2 A273V/A273V LUAD, suggesting that c-fos and CEACAM6 may be potential therapeutic targets for LUAD | (16) |

| LUAD, LUSC, SCLC, LCNEC | Surgery bronchoscopy; pleural effusion; CTCs; sputum | Wnt pathway inhibitor (T5224) | Wnt pathway inhibitor T5224 suppressed metastasis in NKX2-1-deficient LUAD organoids, suggesting the Wnt pathway is a potential target for lung adenocarcinoma therapy | (8) |

| Osimertinib-resistant lung cancer | Patient-derived lung cancer tissues | Gefitinib, osimertinib | Knockout of DCLK1 restores sensitivity to gefitinib and osimertinib in EGFR-TKI-resistant cells | (17) |

| NSCLC with EGFR mutations, KRAS mutations, and ALK rearrangements |

Surgically removed tissue | CD73 | Pharmacological or genetic inhibition of EGFR, MEK, KRAS, or ALK significantly reduced CD73 mRNA and protein expression in NSCLC cancer cells and PDOs | (19) |

| NSCLC | Derived from patients | EGFR/ERBB2 inhibitors, MEK inhibitors | The ‘KDS30’ assay can predict the response of lung and pancreatic cancer patients to combination therapy with EGFR/ERBB2 (neratinib, lapatinib, dacomitinib, gefitinib, osimertinib) and MEK inhibitors (cobimetinib, trametinib, selumetinib) | (21) |

| SCLC | Derived from patients | Dasatinib | YES1 (tyrosine kinase) is a novel druggable oncogenic target and biomarker | (22) |

| NSCLC | Hydrothorax | Amivantamab | Amivantamab demonstrates antitumor activity in multiple EGFR Exon20ins-driven NSCLC-PDOs | (23) |

| Advanced LUAD | Malignant effusions, brain metastasis, bone metastasis, lung primary tumor | Combine with dabrafenib and trametinib, afatinib, poziotinib, pralsetinib, gefitinib, erlotinib, osimertinib, lazertinib, dacomitinib | Demonstrated the clinical relevance of NSCLC-PDOs | (24) |

| NSCLC | Surgically obtained tissue | JAK inhibitor (TP-0903 and ruxolitinib) | PDO obtained from tumors with high AXL and JAK1 were sensitive to TP-0903 and ruxolitinib treatments, supporting the CyTOF findings | (25) |

| ALK-translocated LUAD | Surgical removal of tumor tissue, MPE | Crizotinib, alectinib, brigatinib | The CODRP index more accurately discriminates the sensitivity and resistance to ALK-targeted therapies in ALK-rearranged positive and negative patients, correlating with clinical patients’ therapeutic responses to the drugs | (26) |

| LUAD, LUSC, SCLC, ASC, pulmonary sarcomatous carcinoma | MSE (pleural fluid, ascitic fluid, pericardial effusion), surgical removal of tumor tissue (primary or metastatic lesions); biopsy | Chemotherapy drugs and targeted drugs | LCO-DSTs can accurately predict the clinical response to treatment in advanced lung cancer patients | (7) |

| LUAD | – | Afatinib, T-DM1, lower dose pyrotinib, higher dose pyrotinib | Compared with afatinib, T-DM1 or lower dose pyrotinib, higher dose pyrotinib inhibited the growth of HER2-mutant cancer in both the HER2YVMA insertion PDOs | (27) |

ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; ASC, adenosquamous carcinoma; AXL, Axl receptor tyrosine kinase; CODRP, cancer organoid-based diagnosis reactivity prediction; CSC, cancer stem cell; CTC, circulating tumor cell; CyTOF, cytometry by time-of-flight; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; Exon20ins, exon 20 insertion mutation; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; GSTP1, glutathione S-transferase pi; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; JAK1, Janus kinase 1; KRAS, Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; LCNEC, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma; LCO, lung cancer organoid; LCO-DSTs, LCO-based drug sensitivity tests; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinases, extracellular signal-regulated kinases; MPE, malignant pleural effusion; MSE, malignant serous effusion; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PDO, patient-derived organoid; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibition.

The application of LCOs in predicting drug efficacy

Lung cancer exhibits significant tumor heterogeneity, necessitating extensive preclinical experiments to evaluate various treatment regimens. Drug sensitivity testing based on LCOs (LCO-DST) has been demonstrated to effectively capture the complexity of tumor heterogeneity and show a high degree of concordance with actual patient treatment outcomes (7). This strong correlation underscores the significant value of organoid models in predicting treatment responses and guiding clinical treatment decisions. In precision medicine, LCOs demonstrate a particular ability to select and predict drug treatments for specific patient populations (Table 1). This encompasses the identification of new therapeutic targets (23), the assessment of the effects of specific genetic mutations on drug responses (24,28), and the prediction of reactions to particular drugs (25), including both single-agent and combination therapies (21,24). Yun et al. studied organoids from patients with exon 20 mutations and found that Amivantamab can reduce EGFR-mesenchymal-epithelial transition (EGFR-MET) levels, boost immune responses against tumors, and increase IFN-γ production, thus inhibiting cell growth and serving as a potential TKI for this mutation (23). Early results from the CHRYSALIS I trial showed that Amivantamab was effective against tumors and safe for patients with EGFR exon 20 insertions who had received platinum chemotherapy (29). Amivantamab has also become the first Federal Drug Administration (FDA) approved bispecific molecule for the treatment of solid malignancies (29). Sachs et al. found that in airway organoid models, the 46T TP53 mutation is resistant to Nutlin-3a, the 52MET ERBB2 mutation is sensitive to EGFR/ERBB2 inhibitors, and the 65T ALK1 mutation responds to ALK/c-ros oncogene 1 (ALK/ROS) (28). Kim et al. demonstrated that PDOs are a significant diagnostic tool, with LUAD-PDOs harboring the EGFR L747P mutation being sensitive to afatinib (24). This aligns with clinical findings that the use of afatinib may significantly improve progression-free survival (PFS) in advanced LUAD patients with either the L747P or L747S EGFR mutations (30). Taverna et al. confirmed that PDOs with high Axl receptor tyrosine kinase (AXL) and Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) levels are sensitive to TP-0903 (Axl kinase inhibitor) and ruxolitinib (a JAK inhibitor) treatment through in vitro test (25). Combining neratinib, an EGFR/ERBB2 inhibitor, with cobimetinib, an MEK inhibitor, shows synergistic effects in PDOs with high KDS30 mt KRAS levels (21). Kim et al.’s experimental results showed that the combination therapy of dabrafenib/trametinib induces in vitro and clinical responses in NSCLC with EGFR exon 19 deletion and B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF) G464A mutation (24). A novel method for evaluating ALK-targeted therapies has been developed, which predicts patient responses to various drugs approximately 2 weeks prior to treatment initiation by integrating the growth rate of PDOs and the diagnostic stage of cancer (26). Lee et al.’s study indicates that, certain organoids, such as LC_02T, 03PE, and 04T, had increased resistance to crizotinib, while LC_03PE and 09PE were resistant to alectinib, and LC_04T was resistant to brigatinib, compared to ALK-negative organoids (26). In precision medicine, the significance of LCO-related research lies in their provision of a robust platform for predicting patient responses to specific treatments, evaluating the efficacy of new drugs and combination therapy regimens, and elucidating the impact of specific genetic mutations on drug responses. These models not only preserve key tumor cell variations but also maintain sensitivity to targeted therapies, playing a crucial role in precision medicine. Through these models, researchers can better understand tumor heterogeneity, predict treatment outcomes, and provide more personalized treatment plans for patients.

The application of LCOs in drug screening

LCO has been confirmed to have the potential to serve as a novel preclinical cancer model representative of individual patients (9), which can be employed to assess the therapeutic efficacy of specific drugs or drug combinations and is applicable in drug screening. In a real-world study, LCO-DST was conducted for both chemotherapy and targeted therapy (7). The results indicated that LCO-DST accurately predicted the clinical response to treatment in a cohort of advanced lung cancer patients (7). If the drug sensitivity test outcomes of LCO can be correlated with clinical outcomes, it suggests that these models can accurately predict patients’ responses to treatment, which is of significant importance for drug screening and personalized medicine. Wang et al. demonstrated through in vitro experiments on LCOs with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) exon 20 mutations that high-dose pyrotinib can block the downstream signaling pathway of HER2, inhibit tumor growth, and be more effective than afatinib, T-DM1, or low-dose pyrotinib. Subsequently, this conclusion was validated in a phase II study with 15 patients with HER2 mutant NSCLC, showing an objective response rate (ORR) of 53.3% and a median PFS of 6.4 months (27). The LCO models established by Shi et al. not only retained the sensitivity to EGFR, FGFR, and MEK-targeted therapies that matched their parent tumors but also demonstrated the consistency of gene expression profiles between the organoids and the parent tumor tissues through whole-exome and RNA sequencing (10). LCO derived from various sources, such as surgically resected tumor tissues, biopsy samples, or malignant pleural effusions, can provide a comprehensive view of tumor heterogeneity, which is crucial for simulating the tumor response in the real world. Norman et al. provided a basic framework for selective growth of p53 mutant tumors in primary and metastatic NSCLC, summarizing tumor histology and mutation status, confirming that airway organoids can be used for in vitro drug screening (28). Drug experiments conducted by Peng et al. showed that in LCOs derived from malignant pleural effusion of EGFR+/MET amp+ patients, dual-targeted therapy was more effective than TKI monotherapy (31). To facilitate the widespread application of LCO in clinical drug screening, a crucial prerequisite is the optimization of workflows and the reduction of the turnaround time for organoid generation and drug sensitivity testing (32). This necessity stems partly from the heterogeneity of tumors, where different cancers or even different parts of the same tumor may progress at varying rates. Recent studies have successfully identified methods for rapidly assessing drug responses in LCO, which holds the potential to enhance the efficiency and timeliness of clinical applications. Hu et al. developed a microarray chip-based drug sensitivity test using LCO that can predict drug responses within a week (13). Lee et al.’s drug sensitivity test based on the cancer organoid-based diagnosis reactivity prediction (CODRP) index not only reliably classified patients’ responses to EGFR-TKI therapy within a clinical timeframe of 10 days but also demonstrated significant correlation with clinical outcomes (33). Takahashi et al. confirmed that the 384-well plate High Throughput Screening (HTS) system is suitable for in vitro evaluation of LCO sensitivity to molecular targeted drugs (including small molecule inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, and antibody-drug conjugates) and chemotherapy drugs (34). Research conducted thus far has amply demonstrated the significance of LCOs as a crucial model for drug screening. However, there are currently variations in protocols for organoid culture and DST across different laboratories, which may lead to inconsistent and non-reproducible results (32). This poses a challenge to the reliability of clinical decision-making and research. Future efforts must establish stringent quality control standards to standardize the culture environment and reliability of organoids.

The application of LCOs in drug resistance

In recent years, extensive research has utilized LCOs to establish drug resistance models, aiming to explore the mechanisms of drug resistance and identify new strategies to reverse it (Table 2). A LUAD-PDOs model that preserves the biologic features of human metastases has been established to study the response of KRASG12C-mutated PDOs to sotorasib (35). It was found that sotorasib effectively inhibits metastasis and reduces cellular viability, confirming that PDOs can be a powerful tool for studying lung cancer metastasis and assessing resistance to targeted therapies (35). Research based on EGFR-TKI resistance models has shown that methanesulfonamide (MA; a natural PLA2 inhibitor) (50), compound Z11 (an effective CDK9 inhibitor) (36), and BI-4732 (a fourth-generation EGFR-TKI) (37), could be potential options for treating NSCLC patients with osimertinib-resistant. Li et al., using an osimertinib-resistant LUAD model, discovered that RNA-binding motif protein 15 (RBM15) enhances the m6A modification of SPOCK1 mRNA, activates bypass pathways, promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and thereby mediates osimertinib resistance (38). It was concluded that RBM15 is a key factor in reversing EGFR-TKI resistance and, as a therapeutic target, has the potential to extend the benefits of TKI treatment for patients with LUAD (38). The research findings by Yu et al. demonstrate that PIK3CA mutations lead to resistance to EGFR-TKIs in NSCLC through the activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (39). The combined use of BYL719, a PI3Kα inhibitor, and gefitinib can overcome this resistance by dual inhibition of the signaling pathway (39). Yan et al. demonstrated that inhibiting DCLK1 expression can enhance the sensitivity of EGFR-TKI resistant cells and organoids to EGFR-TKIs, highlighting DCLK1 inhibitor (DCLKI-IN-1) as a potential targeted treatment option for wild-type EGFR patients post resistance development (17). In addition, DCLK1 plays a crucial role in maintaining the stem-like characteristics of tumor cells, which helps to avoid the targeted killing of EGFR-TKIs (17). Wang et al. utilized organoids derived from ALK-rearranged LUAD patients to show that combination therapy of ezatiostat (a specific GSTP1 inhibitor) and crizotinib (an ALK inhibitor) can modulate lung CSC activity and inhibit TKI-resistant LADC organoid proliferation (15). Furthermore, LCOs are employed to test the synergistic effects of various drug combinations in the quest for new therapies to overcome drug resistance. Research on cisplatin-resistant organoids indicates that halofuginone (HF; a natural small molecule) (40), solamargine (a natural small molecule) (41), or dihydroartemisinin (DHA) (42) used in combination with cisplatin (DDP) individually represent promising strategies to overcome chemotherapy resistance in lung cancer patients. Targeting aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) (43) or phosphofructokinase, platelet (PFKP) (44) can also enhance the sensitivity of LUAD patients to platinum-based chemotherapy. Suvilesh et al., by establishing patient-derived tumor organoids (PDTO) from NSCLC, discovered that the use of the AKR1B10 inhibitor epalrestat can overcome chemoresistance in NSCLC (45). LCO can also be utilized to assess resistance to radiotherapy. Zhang et al. propose that nitric oxide (NO) promotes the S-nitrosylation and deubiquitination of Notch1 protein, thereby maintaining CSCs in NSCLC (46). Targeting NO can effectively reduce the CSC population within PDOs during radiotherapy, presenting a promising therapeutic target for overcoming radiotherapy resistance in NSCLC treatment (46). LCOs, capable of replicating the cellular traits and mutational heterogeneity of human cancers, have become essential tools for investigating resistance mechanisms and devising innovative treatment approaches, with initial clinical validation already achieved. Lim et al. have validated a novel EGFR-TKI inhibitor, BLU-945, for its antitumor activity against osimertinib-resistant NSCLC cells and organoids (47). Subsequently, the SYMPHONY phase I/II trial, a global first-in-human study, has demonstrated that BLU-945, as a promising next-generation EGFR-TKI, holds potential therapeutic value for patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC who have developed resistance following prior EGFR-TKI treatment (48). In a clinical retrospective study involving thirteen patients with advanced NSCLC who harbored the BRAF V600E mutation post-EGFR-TKI therapy, the combination therapy of dabrafenib, trametinib, and osimertinib yielded a median PFS of 13.5 months (95% confidence interval: 6.6–20.4) with an ORR of 61.5% (49). Validation through PDOs revealed that this treatment was highly effective, with significantly lower half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values compared to other treatment regimens, achieving a 99.36% inhibition of tumor growth, confirming the efficacy of the triple therapy in patients with EGFR-mutated and BRAF V600E-resistant disease (49). Xie et al. reported a case of a patient with ceritinib-resistant lung cancer who maintained the original ALK-rearrangement without acquired mutations, and sequential treatment with brigatinib and lorlatinib resulted in PFS durations of 3.2 and 1.9 months, respectively, aligning with drug sensitivity testing outcomes from LCOs (51). Additionally, LCOs can exhibit cellular state transitions, a key mechanism in the development of drug resistance. Researchers, using a LUAD organoid model co-mutated for KRASG12C and STK11/LKB1, found that treatment with KRASG12C inhibitors, such as adagrasib, induced an adenosquamous transformation (AST) in KRAS/LKB1-mutated LUAD organoids, leading to drug resistance (52). The key factor ΔNp63 drives this process, and AST plasticity signatures along with Keratin 6A (KRT6A) expression levels may serve as predictive biomarkers for drug resistance (52). Recent advancements have witnessed a surge in research utilizing LCOs to establish drug resistance models and explore novel therapeutic strategies. However, the transition from preclinical to clinical applications remains a formidable challenge. It has been observed that the evidence linking clinical observational data with experimental results from LCOs is often limited by small sample sizes. This limitation is further compounded by the variability in LCO cultivation methods across different laboratories and the fact that the success rate of establishing LCO models is not 100%. Consequently, the immediate translation of experimental outcomes from organoid models into clinical practice is not feasible with the current experimental methods (24). Instead, the current strength of LCOs lies in their utility as an assessment tool for in vitro testing, which allows for the evaluation of the therapeutic compatibility between a specific individual or a cohort sharing common characteristics and a given drug.

Table 2

| LCOs based on subtypes | Organizational sources | Therapy | Related drugs or targets | Main results in drug resistance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LUAD | Surgical removal of tumor tissue (primary or metastatic lesions); MPE | Targeted therapy | Osimertinib, sotorasib | The model can examine the efficacy of treatments to suppress metastasis and identify mechanisms of drug resistance | (35) |

| NSCLC | Derived from patients | Osimertinib-resistant | Compound Z11, a potent CDK9 inhibitor | Z11 served as a promising macrocycle-based CDK9 inhibitor for treating osimertinib-resistant NSCLC | (36) |

| NSCLC | MPE | Targeted therapy | BI-4732, a novel fourth-generation EGFR-TKI | BI-4732 is a novel and potent EGFR inhibitor targeting activating mutations and resistance to EGFR-targeted therapy in NSCLC | (37) |

| LUAD | Biopsy | Targeted therapy | RBM15 | Early targeting of RBM15 during EGFR-TKI treatment could dramatically extend the patient response and benefit from TKI therapy | (38) |

| LUAD | MPE | Targeted therapy | Gefitinib, BYL719 (a PI3Kα inhibitor) | The combined effect and mechanism of gefitinib and BYL719 were confirmed in the NSCLC cells and PDOs | (39) |

| LUAD | Surgery samples, transbronchial biopsies | Cisplatin-resistant | HF, cisplatin | HF could sensitize the cisplatin-resistant LCOs | (40) |

| LUAD, LUSC | Surgical samples, transbronchial biopsies | Chemotherapy | Solamargine | Solamargine as a hedgehog pathway inhibitor and cisplatin-sensitizer | (41) |

| Lung cancer | Patient-derived tissue | Chemotherapy | DHA, cisplatin | Combining DHA with cisplatin presents a promising strategy to overcome chemoresistance in lung cancer patients | (42) |

| LUAD | LUAD tumor tissues | Chemotherapy | ALDH2, platinum | Targeting ALDH2 is a promising new strategy to enhance the sensitivity of platinum-based chemotherapy for the treatment of LUAD patients | (43) |

| NSCLC | Surgical removal of tumor tissue | Chemotherapy | Cisplatin, paclitaxel | PFKP can regulate the expression of ABCC2 through the activation of NF-κB, which promotes chemoresistance in NSCLC | (44) |

| LUAD, LUSC | Surgical removal of tumor tissue | Chemotherapy | Cisplatin, paclitaxel | AKR1B10 can be targeted by repurposing epalrestat to overcome chemoresistance in NSCLC | (45) |

| NSCLC | Patient-derived tumor tissue | Radiotherapy | NO | Targeting nitric oxide effectively reduced CSC populations within PDOs during radiotherapy | (46) |

| NSCLC | MPE | Targeted therapy, osimertinib-resistant | BLU-945, osimertinib | BLU-945 demonstrated in vivo tumor shrinkage in osimertinib-resistant models of NSCLC (osimertinib second line: EGFR_L858R/C797S and third line: EGFR_ex19del/T790M/C797S and L858R/T790M/C797S) both as monotherapy and in combination with osimertinib | (47) |

| NSCLC | Malignant effusions | Targeted therapy | BLU-945 | BLU-945 is a potent, reversible, wild-type-sparing inhibitor of EGFR+/T790M and EGFR+/T790M/C797S resistance mutants that maintains activity against the sensitizing mutations, especially L858R | (48) |

| NSCLC | Malignant effusion | Targeted therapy | Dabrafenib, trametinib, osimertinib | EGFR/BRAF/MEK triple-targeted therapy is an effective and safe approach for treating EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients resistant to EGFR-TKIs with acquired BRAF V600E mutations | (49) |

BRAF, B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase; CSC, cancer stem cell; DHA, dihydroartemisinin; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HF, halofuginone; LCO, lung cancer organoid; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; MPE, malignant pleural effusion; NO, nitric oxide; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PDO, patient-derived organoid; PFKP, phosphofructokinase, platelet; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibition.

Organoid-immune co-culture establishment

ICIs differ from cytotoxic chemotherapy and targeted therapy in that they activate anti-tumor immunity by blocking T cell co-inhibitory signals (53). However, tumor heterogeneity leads many patients to eventually develop acquired resistance to ICIs (54). Currently, our ability to predict the mechanisms of ICI resistance and treatment efficacy is limited, primarily relying on long-term follow-up and clinical data. Most PDOs lack a specific ratio of immune cell composition in culture (55), coupled with the short lifespan characteristic of immune cells (33), which prevents the reconstruction of the tumor microenvironment (TME) (56). Cancer organoid co-culture models have been proposed to address this issue. This system ingeniously integrates the cellular components of the TME, including T cells, into the cancer organoid cultures, better replicating the TME and thus providing a research platform closer to in vivo conditions (57,58). Specifically, within the context of either the extracellular matrix (ECM) or the liquid culture medium, fully developed organoids are supplemented with stimulated immune cells, including T lymphocytes and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), to assess the interplay between these immune components and the epithelial cells (57). Co-culturing cancer organoids with patients’ own peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) to induce tumor-specific cytotoxic T cells is a widely adopted method (59,60). This includes maintaining and expanding natural immune cells within organoids or directly adding immune cells to the culture (61). Dijkstra et al. co-cultured colorectal cancer (CRC) or NSCLC organoids with autologous circulating T cells and successfully expanded tumor-reactive T cells paired with PBMC (59). Two weeks later, CD107a upregulation and IFN-γ secretion were observed in the NSCLC co-culture, with 2 out of 6 NSCLC patients producing LCO and 2 out of 6 NSCLC patients obtaining autologous tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells (59). Cattaneo et al. also established organoids from tumor samples of NSCLC and microsatellite unstable CRC patients, co-culturing them with peripheral blood lymphocytes for two weeks, using IFN-γ to stimulate tumor cells to expand tumor-reactive T cells (62). Results from T cell-organoid killing assays showed that altering the ratio of T cells to tumor cells could significantly change the observed level of tumor killing (62). Wang et al. used co-culture model to assess the immunobiological effects of serum amyloid A (SAA) secreted by CSCs (63). The experiment introduced anti-programmed death-1 (α-PD-1) and SAA-neutralizing antibodies to evaluate T cell reactivity and killing ability against tumors (63). The results indicated that SAA promotes chemotherapy resistance, inhibits anti-tumor immunity, and exacerbates tumor fibrosis by driving a TH2-type immune response (63). To validate the therapeutic effect of inhibiting metastasis and determine resistance mechanisms, Liu et al. co-cultured pre-treated PDOs with chemotherapy or radiation therapy with autologous PBMCs (35). The results showed that the addition of the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab could activate CD8+ T cells and increase tumor cell death levels (35). Notably, PDOs pre-treated with radiotherapy demonstrated more effective immune activation capabilities in co-culture (35). This finding provides theoretical support for the treatment of LUAD and aids in the development of personalized immunotherapy strategies. Macrophages are highly abundant in the innate immune infiltration of NSCLC TME and can be systematically incorporated into NSCLC organoids derived from wild-type tissues, generating dynamic crosstalk (64). The establishment of organoid-macrophage co-culture models contributes to the exploration of macrophage-targeted therapy in NSCLC immunotherapy, opening up new frontiers for NSCLC treatment (64). Chen et al. reported a three-dimensional (3D) co-culture system of LUSC epithelial cells with cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and ECM (65). This model can summarize the key pathological changes from tumor proliferation to dysplasia and ultimately invasion, providing fundamental evidence for the dynamic interaction between LUSC cells and the components of the TME (65). Patient-derived organotypic tissue cultures (PD-OTCs) of NSCLC offer a comprehensive model that captures the metabolic reprogramming observed in patient tumors and provides a platform to study immune metabolic responses to therapeutic modulators, as well as the emergence of resistance within the TME (66). Concurrently, recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy of organoid technology in the reprogramming of T lymphocytes, which significantly amplifies tumor cell vulnerability to T cell-mediated cytotoxic attacks, highlighting the dual utility of organoids in advancing our understanding of both metabolic and immunological dynamics in cancer (67). Although CD8+ T cells are the most powerful effectors in anti-cancer immune responses, reflecting the therapeutic effects of ICIs (68,69), this co-culture model also has limitations, as isolated immune cell populations, such as T cells or PBMCs, cannot fully represent the complexity and heterogeneity of the entire immune system (70). Anti-cancer immune responses require the cooperation of tumor-infiltrating innate immune cells and adaptive immune cells [such as neutrophils, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells (DCs), and T cells] within the tumor tissue. New methods have been proposed to address the current challenges (71). Luan et al. proposed an agarose micropore platform specifically designed for PDO-based tumor and TME models, capable of rapid drug screening and resistance studies with small sample sizes (72). Various cell types, including cancer cells, fibroblasts, immune cells, and endothelial cells, have been integrated into various microfluidic co-culture platforms, successfully demonstrating cancer phenotype modeling and drug response outcomes (72). A novel air-liquid interface (ALI)-based organoid generation platform has also been successfully established and has been shown to accurately preserve T cells, CAFs, and CD31+ endothelial cells in renal cell carcinoma organoids (73). Therefore, the co-culture model needs further improvement to better reflect the interactions between tumors and immune cells (58). Although the current co-culture models cannot fully replicate the complex mechanisms and interactions found in the TME under cancerous conditions, it cannot be denied that they are a promising tool for simulating changes in the immune microenvironment of lung tissue under different pathological states. Studies have already utilized organoid culture technology to simulate the alveolar microenvironment (74,75). DJ-1 (an antioxidant protein) controls goblet cell metaplasia and eosinophil infiltration by affecting the interaction between airway progenitor cells and immune cells (75). During the critical period of alveolar epithelial cell (AEC2) proliferation, there is an accumulation of CD115+ and CCR2+ monocytes as well as M2-like macrophages in lung tissue (74). Furthermore, the co-culture study of mouse airway club progenitor cells and CD11b macrophages showed that the Lkb1 defect in mouse airway club progenitor cells promoted the expression of FIZZ1/RELM-α (resistin-like molecule-α), leading to airway goblet cell differentiation and lung macrophage recruitment (76). The process of simulating the alveolar microenvironment using organoid culture emphasizes the role of immune cells in promoting lung regeneration and repair. In contrast, in a cancerous state, organoids may exhibit different patterns of interaction between immune cells and tumor cells, such as immune suppression or signaling that promotes tumor growth. These differences highlight the importance of organoids as research tools in simulating and understanding the changes in the immune microenvironment of lung tissue in different pathological states.

Cancer organoids co-cultured with immune cells provide a valuable model system for assessing the sensitivity of individual cancers to immunotherapy at any stage of treatment, which is crucial for evaluating new therapies. This innovative model has been shown to effectively and rapidly assess the impact of ICIs on activating cytotoxic lymphocytes and promoting T cell infiltration, especially in cases of T cell infiltration. Despite the promise of this model, obtaining sufficient high-quality tumor tissues and immune cells remains a challenge, which may limit the widespread application of the model. To overcome these challenges, it may be necessary to develop new techniques to improve the efficiency of sample acquisition and processing or explore alternative models, such as those based on cell lines or genetically engineered models, to enhance the reproducibility and scalability of research.

Discussion

PDO must accurately replicate the unique tumor characteristics of primary cancers, as this directly affects the clinical applicability of the model (77,78). Therefore, it is necessary to study the success rate and accuracy of cultured organoids (61,79). The success of LCO cultivation can be determined by several different factors. First is the aspect of tumor tissue sourced from patients. Current limitations include: (I) the proportion of tumor cells in the initial sample is often insufficient, which is especially common in tissue samples obtained through biopsies (9); (II) tumor tissue may be affected by excessive growth of surrounding normal tissue (80), resulting in almost no cancer cells in late passages of LCO (81). Previous studies have indicated that organoids can be generated from metastatic tissue or malignant effusions (33), thereby allowing for the exclusion of normal lung cells to address this limitation (82,83). Second, is the aspect of long-term amplification of organoids. Current limitations include: (I) the lack of medium formulations specifically for LCOs, leading to limited success rates and tumor purity (84); (II) the short lifespan of organoids is a major factor limiting their ability to reach later developmental stages and acquire mature phenotypic capabilities (12). Regarding the culture medium, researchers believe that the inducing factors for tumor organoids vary due to individual heterogeneity (12), thus requiring screening of various cytokines and small molecules to optimize the culture medium for LCOs (78). Acosta-Plasencia et al. (84) evaluated three types of media, including permissive culture medium (PCM), limited culture medium (LCM), and minimal basal medium (MBM), showing that while PCM is associated with the highest success rate and aids in long-term amplification, MBM is the best choice for avoiding excessive growth of normal organoids in culture. Due to the high metabolic demands of organoid growth, necrotic cores form within the hydrogel structure; however, new methods are being researched to reconfigure the 3D environment of organoids, removing the necrotic centers of the hydrogel while retaining the outer layer containing viable organoids (85). When the LCO culture medium can successfully establish organoids, facilitate long-term amplification, and maintain the purity of cancer cells in culture, it is considered optimal (84). However, currently, no medium meets all requirements. Encouragingly, an increasing number of studies are emerging to propose more suitable culture methods for different subtypes. Malmros et al. (86) used four different methods to culture NSCLC cell lines in 3D, showing that adenocarcinoma cell lines (A549, NCI-H1975) retained their original immunohistochemical (IHC) characteristics, while squamous cell carcinoma (HCC-95, HCC-1588) lost their unique markers during culture. This suggests that different media may have varying impacts on the phenotypic and molecular characteristics of the cells. Choi et al. (77) validated WRNA culture conditions (including Wnt3A, R-spondin1, Noggin, and A8301) for the long-term culture of SCLC organoids. The study also indicated that although culture conditions are crucial for the long-term survival of organoids, they do not affect the genomic stability or representativeness of the organoids. For LADC organoids, the mechanical dissociation method using a 10 mL Stripette serum pipette to crush organoids into small fragments is a better choice compared to traditional enzymatic digestion methods (14). There is still a long way to go in the future, requiring the development of optimized culture protocols suitable for different subtypes of lung cancer. This not only necessitates proposing and conducting extensive experimental validations, including determining the optimal medium components, exploring processing methods for tumor tissues from different sources, long-term culture conditions, freezing and recovery conditions, etc., but also ensuring the genetic stability of phenotypes in organoids during long-term culture and passage, ultimately leading to the formulation of standardized LCO culture protocols.

At this stage, LCOs as disease models are developing rapidly and are unstoppable. The LCOs biobank has been established, which includes tumor tissue samples along with paired clinical information. This facilitates purposeful cryopreservation and revival during targeted experimental research, is applicable for high-throughput drug screening and drug efficacy prediction, and allows for targeted drug screening of specific mutations/subtypes of LCOs. In addition to serving as disease research models, LCOs can also act as platforms for new drug development. Naranjo et al. developed immunocompetent organoid-based models of KRAS, BRAF, and ALK mutant LUAD, aiding in the study of lung cancer immunotherapy (87). Liu et al. constructed a platform combining phenotype and transcriptomics, called FascRNA-seq, to analyze the dynamic response of the local immune microenvironment under immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy (88). Notably, the concept of ‘tumour assembloids’ has recently been proposed, which is defined as self-organizing cellular systems composed of different organ or cell types (89). It emphasizes the interactions between various cells in a 3D space, particularly cancer cells and tumor-associated cells, aimed at creating more realistic simulations of PDTO within the TME (90). Another significant aspect is that LCOs provide researchers with the ability to assess the real-time effects of therapeutic interventions, which is especially important for studying lung cancer with high heterogeneity and contributes to the development of personalized treatment strategies. Additionally, the integration of organoid technology with 3D bioprinting and novel biomaterials, along with gene editing, multi-omics analysis, and artificial intelligence, will become future development trends. This interdisciplinary advancement also offers new opportunities for LCO-immunocyte co-culture models. It not only allows for the assessment of individual cancer sensitivity to immunotherapy at various stages of treatment but also provides an important platform for the development and evaluation of new immunotherapies, thereby promoting the progress of personalized precision medicine.

Conclusions

LCOs as a new strategy in precision medicine research, not only provide a powerful experimental platform for evaluating new treatment strategies and exploring biomarkers but also contribute to a deeper understanding of drug resistance mechanisms. Despite challenges in cultivation success rate and accuracy, significant progress has been made through technological innovation. This has not only improved the clinical relevance of the models but also provided new perspectives for personalized treatment. In the future, further optimization of LCO cultivation techniques and addressing the current limitations of cancer organoid co-culture models will be of great significance in promoting the development of precision medicine for lung cancer.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Peer Review File: Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-921/prf

Funding: This study was funded by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-921/coif). F.K. states that this study was supported by the above-mentioned funding programs and that there were no other conflicts of interest. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Marjanovic ND, Hofree M, Chan JE, et al. Emergence of a High-Plasticity Cell State during Lung Cancer Evolution. Cancer Cell 2020;38:229-246.e13. [PubMed]

- Dagogo-Jack I, Shaw AT. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018;15:81-94. [PubMed]

- Fang W, Jin H, Zhou H, et al. Intratumoral heterogeneity as a predictive biomarker in anti-PD-(L)1 therapies for non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer 2021;20:37. [PubMed]

- Yoshida GJ. Applications of patient-derived tumor xenograft models and tumor organoids. J Hematol Oncol 2020;13:4. [PubMed]

- Franklin MR, Platero S, Saini KS, et al. Immuno-oncology trends: preclinical models, biomarkers, and clinical development. J Immunother Cancer 2022;10:e003231. [PubMed]

- Long Y, Xie B, Shen HC, et al. Translation Potential and Challenges of In Vitro and Murine Models in Cancer Clinic. Cells 2022;11:3868. [PubMed]

- Wang HM, Zhang CY, Peng KC, et al. Using patient-derived organoids to predict locally advanced or metastatic lung cancer tumor response: A real-world study. Cell Rep Med 2023;4:100911. [PubMed]

- Ebisudani T, Hamamoto J, Togasaki K, et al. Genotype-phenotype mapping of a patient-derived lung cancer organoid biobank identifies NKX2-1-defined Wnt dependency in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Rep 2023;42:112212. [PubMed]

- Kim M, Mun H, Sung CO, et al. Patient-derived lung cancer organoids as in vitro cancer models for therapeutic screening. Nat Commun 2019;10:3991. [PubMed]

- Shi R, Radulovich N, Ng C, et al. Organoid Cultures as Preclinical Models of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26:1162-74. [PubMed]

- Chen JH, Chu XP, Zhang JT, et al. Genomic characteristics and drug screening among organoids derived from non-small cell lung cancer patients. Thorac Cancer 2020;11:2279-90. [PubMed]

- Wu M, Liao Y, Tang L. Non-small cell lung cancer organoids: Advances and challenges in current applications. Chin J Cancer Res 2024;36:455-73. [PubMed]

- Hu Y, Sui X, Song F, et al. Lung cancer organoids analyzed on microwell arrays predict drug responses of patients within a week. Nat Commun 2021;12:2581. [PubMed]

- Li Z, Qian Y, Li W, et al. Human Lung Adenocarcinoma-Derived Organoid Models for Drug Screening. iScience 2020;23:101411. [PubMed]

- Wang SQ, Chen JJ, Jiang Y, et al. Targeting GSTP1 as Therapeutic Strategy against Lung Adenocarcinoma Stemness and Resistance to Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2023;10:e2205262. [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Chudgar N, Mastrogiacomo B, et al. A germline SNP in BRMS1 predisposes patients with lung adenocarcinoma to metastasis and can be ameliorated by targeting c-fos. Sci Transl Med 2022;14:eabo1050. [PubMed]

- Yan R, Fan X, Xiao Z, et al. Inhibition of DCLK1 sensitizes resistant lung adenocarcinomas to EGFR-TKI through suppression of Wnt/β-Catenin activity and cancer stemness. Cancer Lett 2022;531:83-97. [PubMed]

- Pan Y, Han H, Hu H, et al. KMT2D deficiency drives lung squamous cell carcinoma and hypersensitivity to RTK-RAS inhibition. Cancer Cell 2023;41:88-105.e8. [PubMed]

- Han Y, Lee T, He Y, et al. The regulation of CD73 in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 2022;170:91-102. [PubMed]

- Lin S, Li Y, Wang D, et al. Fascin promotes lung cancer growth and metastasis by enhancing glycolysis and PFKFB3 expression. Cancer Lett 2021;518:230-42. [PubMed]

- Tyc KM, Kazi A, Ranjan A, et al. Novel mutant KRAS addiction signature predicts response to the combination of ERBB and MEK inhibitors in lung and pancreatic cancers. iScience 2023;26:106082. [PubMed]

- Redin E, Garrido-Martin EM, Valencia K, et al. YES1 Is a Druggable Oncogenic Target in SCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2022;17:1387-403. [PubMed]

- Yun J, Lee SH, Kim SY, et al. Antitumor Activity of Amivantamab (JNJ-61186372), an EGFR-MET Bispecific Antibody, in Diverse Models of EGFR Exon 20 Insertion-Driven NSCLC. Cancer Discov 2020;10:1194-209. [PubMed]

- Kim SY, Kim SM, Lim S, et al. Modeling Clinical Responses to Targeted Therapies by Patient-Derived Organoids of Advanced Lung Adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27:4397-409. [PubMed]

- Taverna JA, Hung CN, DeArmond DT, et al. Single-Cell Proteomic Profiling Identifies Combined AXL and JAK1 Inhibition as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy for Lung Cancer. Cancer Res 2020;80:1551-63. [PubMed]

- Lee SY, Cho HJ, Choi J, et al. Cancer organoid-based diagnosis reactivity prediction (CODRP) index-based anticancer drug sensitivity test in ALK-rearrangement positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2023;42:309. [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Jiang T, Qin Z, et al. HER2 exon 20 insertions in non-small-cell lung cancer are sensitive to the irreversible pan-HER receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor pyrotinib. Ann Oncol 2019;30:447-55. [PubMed]

- Sachs N, Papaspyropoulos A, Zomer-van Ommen DD, et al. Long-term expanding human airway organoids for disease modeling. EMBO J 2019;38:e100300. [PubMed]

- Brazel D, Nagasaka M. The development of amivantamab for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Respir Res 2023;24:256. [PubMed]

- Liang SK, Ko JC, Yang JC, et al. Afatinib is effective in the treatment of lung adenocarcinoma with uncommon EGFR p.L747P and p.L747S mutations. Lung Cancer 2019;133:103-9. [PubMed]

- Peng KC, Su JW, Xie Z, et al. Clinical outcomes of EGFR+/METamp+ vs. EGFR+/METamp- untreated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer 2022;13:1619-30. [PubMed]

- Xiang D, He A, Zhou R, et al. Building consensus on the application of organoid-based drug sensitivity testing in cancer precision medicine and drug development. Theranostics 2024;14:3300-16. [PubMed]

- Lee SH, Kim K, Lee E, et al. Prediction of TKI response in EGFR-mutant lung cancer patients-derived organoids using malignant pleural effusion. NPJ Precis Oncol 2024;8:111. [PubMed]

- Takahashi N, Hoshi H, Higa A, et al. An In Vitro System for Evaluating Molecular Targeted Drugs Using Lung Patient-Derived Tumor Organoids. Cells 2019;8:481. [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Lankadasari M, Rosiene J, et al. Modeling lung adenocarcinoma metastases using patient-derived organoids. Cell Rep Med 2024;5:101777. [PubMed]

- Wu T, Yu B, Xu Y, et al. Discovery of Selective and Potent Macrocyclic CDK9 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Osimertinib-Resistant Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Med Chem 2023;66:15340-61. [PubMed]

- Lee EJ, Oh SY, Lee YW, et al. Discovery of a Novel Potent EGFR Inhibitor Against EGFR Activating Mutations and On-Target Resistance in NSCLC. Clin Cancer Res 2024;30:1582-94. [PubMed]

- Li H, Li Y, Zheng X, et al. RBM15 facilitates osimertinib resistance of lung adenocarcinoma through m6A-dependent epigenetic silencing of SPOCK1. Oncogene 2025;44:307-21. [PubMed]

- Yu Y, Xiao Z, Lei C, et al. BYL719 reverses gefitinib-resistance induced by PI3K/AKT activation in non-small cell lung cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2023;23:732. [PubMed]

- Li H, Zhang Y, Lan X, et al. Halofuginone Sensitizes Lung Cancer Organoids to Cisplatin via Suppressing PI3K/AKT and MAPK Signaling Pathways. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021;9:773048. [PubMed]

- Han Y, Shi J, Xu Z, et al. Identification of solamargine as a cisplatin sensitizer through phenotypical screening in cisplatin-resistant NSCLC organoids. Front Pharmacol 2022;13:802168. [PubMed]

- Yang Z, Zhou Z, Meng Q, et al. Dihydroartemisinin Sensitizes Lung Cancer Cells to Cisplatin Treatment by Upregulating ZIP14 Expression and Inducing Ferroptosis. Cancer Med 2024;13:e70271. [PubMed]

- Shan G, Bian Y, Yao G, et al. Targeting ALDH2 to augment platinum-based chemosensitivity through ferroptosis in lung adenocarcinoma. Free Radic Biol Med 2024;224:310-24. [PubMed]

- Wang Z, Wu S, Chen X, et al. PFKP confers chemoresistance by upregulating ABCC2 transporter in non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2023;12:2294-309. [PubMed]

- Suvilesh KN, Manjunath Y, Nussbaum YI, et al. Targeting AKR1B10 by Drug Repurposing with Epalrestat Overcomes Chemoresistance in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patient-Derived Tumor Organoids. Clin Cancer Res 2024;30:3855-67. [PubMed]

- Zhang T, Lei J, Zheng M, et al. Nitric oxide facilitates the S-nitrosylation and deubiquitination of Notch1 protein to maintain cancer stem cells in human NSCLC. J Cell Mol Med 2024;28:e70203. [PubMed]

- Lim SM, Schalm SS, Lee EJ, et al. BLU-945, a potent and selective next-generation EGFR TKI, has antitumor activity in models of osimertinib-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2024;16:17588359241280689. [PubMed]

- Eno MS, Brubaker JD, Campbell JE, et al. Discovery of BLU-945, a Reversible, Potent, and Wild-Type-Sparing Next-Generation EGFR Mutant Inhibitor for Treatment-Resistant Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Med Chem 2022;65:9662-77. [PubMed]

- Weng CD, Liu KJ, Jin S, et al. Triple-targeted therapy of dabrafenib, trametinib, and osimertinib for the treatment of the acquired BRAF V600E mutation after progression on EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer patients. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2024;13:2538-48. [PubMed]

- Ni Y, Liu J, Zeng L, et al. Natural product manoalide promotes EGFR-TKI sensitivity of lung cancer cells by KRAS-ERK pathway and mitochondrial Ca(2+) overload-induced ferroptosis. Front Pharmacol 2022;13:1109822. [PubMed]

- Xie Y, Zhang Y, Wu Y, et al. Analysis of the resistance profile of real-world alectinib first-line therapy in patients with ALK rearrangement-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer using organoid technology in one case of lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2024;16:3854-63. [PubMed]

- Tong X, Patel AS, Kim E, et al. Adeno-to-squamous transition drives resistance to KRAS inhibition in LKB1 mutant lung cancer. Cancer Cell 2024;42:413-428.e7. [PubMed]

- Jenkins RW, Barbie DA, Flaherty KT. Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Br J Cancer 2018;118:9-16. [PubMed]

- Schoenfeld AJ, Hellmann MD. Acquired Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancer Cell 2020;37:443-55. [PubMed]

- Recaldin T, Steinacher L, Gjeta B, et al. Human organoids with an autologous tissue-resident immune compartment. Nature 2024;633:165-73. [PubMed]

- Corrò C, Novellasdemunt L, Li VSW. A brief history of organoids. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2020;319:C151-65. [PubMed]

- Bar-Ephraim YE, Kretzschmar K, Clevers H. Organoids in immunological research. Nat Rev Immunol 2020;20:279-93. [PubMed]

- Jeong SR, Kang M. Exploring Tumor-Immune Interactions in Co-Culture Models of T Cells and Tumor Organoids Derived from Patients. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:14609. [PubMed]

- Dijkstra KK, Cattaneo CM, Weeber F, et al. Generation of Tumor-Reactive T Cells by Co-culture of Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes and Tumor Organoids. Cell 2018;174:1586-1598.e12. [PubMed]

- Liu L, Yu L, Li Z, et al. Patient-derived organoid (PDO) platforms to facilitate clinical decision making. J Transl Med 2021;19:40. [PubMed]

- Grönholm M, Feodoroff M, Antignani G, et al. Patient-Derived Organoids for Precision Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Res 2021;81:3149-55. [PubMed]

- Cattaneo CM, Dijkstra KK, Fanchi LF, et al. Tumor organoid-T-cell coculture systems. Nat Protoc 2020;15:15-39. [PubMed]

- Wang X, Wen S, Du X, et al. SAA suppresses α-PD-1 induced anti-tumor immunity by driving T(H)2 polarization in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis 2023;14:718. [PubMed]

- Balážová K, Clevers H, Dost AFM. The role of macrophages in non-small cell lung cancer and advancements in 3D co-cultures. Elife 2023;12:e82998. [PubMed]

- Chen S, Giannakou A, Wyman S, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts suppress SOX2-induced dysplasia in a lung squamous cancer coculture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:E11671-E11680. [PubMed]

- Fan TW, Higashi RM, Lane AN. Metabolic Reprogramming in Human Cancer Patients and Patient-Derived Models. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2024;a041552. [PubMed]

- Chen D, Xu L, Xuan M, et al. Unveiling the functional roles of patient-derived tumour organoids in assessing the tumour microenvironment and immunotherapy. Clin Transl Med 2024;14:e1802. [PubMed]

- Raskov H, Orhan A, Christensen JP, et al. Cytotoxic CD8(+) T cells in cancer and cancer immunotherapy. Br J Cancer 2021;124:359-67. [PubMed]

- Schmidt J, Chiffelle J, Perez MAS, et al. Neoantigen-specific CD8 T cells with high structural avidity preferentially reside in and eliminate tumors. Nat Commun 2023;14:3188. [PubMed]

- Magré L, Verstegen MMA, Buschow S, et al. Emerging organoid-immune co-culture models for cancer research: from oncoimmunology to personalized immunotherapies. J Immunother Cancer 2023;11:e006290. [PubMed]

- Mao Y, Hu H. Establishment of advanced tumor organoids with emerging innovative technologies. Cancer Lett 2024;598:217122. [PubMed]

- Luan Q, Pulido I, Isagirre A, et al. Deciphering fibroblast-induced drug resistance in non-small cell lung carcinoma through patient-derived organoids in agarose microwells. Lab Chip 2024;24:2025-38. [PubMed]

- Esser LK, Branchi V, Leonardelli S, et al. Cultivation of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Patient-Derived Organoids in an Air-Liquid Interface System as a Tool for Studying Individualized Therapy. Front Oncol 2020;10:1775. [PubMed]

- Lechner AJ, Driver IH, Lee J, et al. Recruited Monocytes and Type 2 Immunity Promote Lung Regeneration following Pneumonectomy. Cell Stem Cell 2017;21:120-134.e7. [PubMed]

- Li K, Zhang Q, Li L, et al. DJ-1 governs airway progenitor cell/eosinophil interactions to promote allergic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022;150:1178-1193.e13. [PubMed]

- Li Y, Zhang Q, Li L, et al. LKB1 deficiency upregulates RELM-α to drive airway goblet cell metaplasia. Cell Mol Life Sci 2021;79:42. [PubMed]

- Choi SY, Cho YH, Kim DS, et al. Establishment and Long-Term Expansion of Small Cell Lung Cancer Patient-Derived Tumor Organoids. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:1349. [PubMed]

- Ma HC, Zhu YJ, Zhou R, et al. Lung cancer organoids, a promising model still with long way to go. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2022;171:103610. [PubMed]

- Sachs N, de Ligt J, Kopper O, et al. A Living Biobank of Breast Cancer Organoids Captures Disease Heterogeneity. Cell 2018;172:373-386.e10. [PubMed]

- Dijkstra KK, Monkhorst K, Schipper LJ, et al. Challenges in Establishing Pure Lung Cancer Organoids Limit Their Utility for Personalized Medicine. Cell Rep 2020;31:107588. [PubMed]

- Park D, Lee D, Kim Y, et al. Cryobiopsy: A Breakthrough Strategy for Clinical Utilization of Lung Cancer Organoids. Cells 2023;12:1854. [PubMed]

- Lee D, Kim Y, Chung C. Scientific Validation and Clinical Application of Lung Cancer Organoids. Cells 2021;10:3012. [PubMed]

- Li Z, Yu L, Chen D, et al. Protocol for generation of lung adenocarcinoma organoids from clinical samples. STAR Protoc 2021;2:100239. [PubMed]

- Acosta-Plasencia M, He Y, Martínez D, et al. Selection of the Most Suitable Culture Medium for Patient-Derived Lung Cancer Organoids. Cells Tissues Organs 2024; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park SE, Kang S, Paek J, et al. Geometric engineering of organoid culture for enhanced organogenesis in a dish. Nat Methods 2022;19:1449-60. [PubMed]

- Malmros K, Kirova N, Kotarsky H, et al. 3D cultivation of non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines using four different methods. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2024;150:472. [PubMed]

- Naranjo S, Cabana CM, LaFave LM, et al. Modeling diverse genetic subtypes of lung adenocarcinoma with a next-generation alveolar type 2 organoid platform. Genes Dev 2022;36:936-49. [PubMed]

- Liu C, Li K, Sui X, et al. Patient-Derived Tumor Organoids Combined with Function-Associated ScRNA-Seq for Dissecting the Local Immune Response of Lung Cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024;11:e2400185. [PubMed]

- Pașca SP, Arlotta P, Bateup HS, et al. A nomenclature consensus for nervous system organoids and assembloids. Nature 2022;609:907-10. [PubMed]

- Mei J, Liu X, Tian HX, et al. Tumour organoids and assembloids: Patient-derived cancer avatars for immunotherapy. Clin Transl Med 2024;14:e1656. [PubMed]