Clinical application of three-dimensional reconstruction in anatomical analysis of the right anterior, lateral, and posterior basal segments (RS8, RS9, and RS10) for RS9 segmentectomy

Highlight box

Key findings

• Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction is a practical tool for analyzing the bronchovascular branching patterns of the RS8, RS9, and RS10 segments. The application of 3D reconstruction is safe and feasible in anatomical RS9 segmentectomy.

What is known and what is new?

• Anatomical RS9 segmentectomy is challenging due the intricate intersegmental planes and varied anatomical structures involved, and few studies have robustly assessed 3D reconstruction techniques for the anatomy and surgical procedures of RS9.

• 3D reconstruction techniques assist thoracic surgeons to better understand the anatomical structures of RS8, RS9, and RS10, and perform RS9 segmentectomy more safely and accurately.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• For anatomical RS9 segmentectomy, 3D reconstruction should be prioritized for anatomical analysis and surgical implementation.

Introduction

With the popularization of computed tomography (CT) screening for lung cancer, an increasing number of early operable pulmonary nodules are being discovered (1). Some studies, such as the JCOG 0802 and CALGB 140503 trials indicate that for patients with early-stage pulmonary nodules, the oncological outcomes of anatomical segmentectomy are not inferior to those of traditional lobectomy (2-5). Consequently, the application of anatomical segmentectomy instead of lobectomy in treating early-stage lung cancer in selected patients has been widely discussed. However, segmentectomy is technically more challenging than lobectomy due to the anatomical complexity and variations of segmental vessels and bronchi, especially in the right lateral basal segment (RS9). Anatomical segmentectomy for RS9 is particularly challenging due to the deeper parenchymal localization of the hilar structures, greater diversity in branching, more frequent variations of segmental vessels and bronchi, and closer proximity of the intersegmental plane (ISP) (6-10).

RS9 is closely adjacent to the anterior and posterior basal segments (RS8 and RS10, respectively) and often shares common vascular and bronchial stems. In contrast, the right medial basal segment (RS7) is relatively independent of RS9 (11). Therefore, a thorough preoperative analysis of the anatomical characteristics and branching patterns of vessels and bronchi in RS8, RS9, and RS10 is critical to achieve precise RS9 segmentectomy. Traditional lung anatomy research is based on the anatomical findings from the cadaver studies conducted by Boyden et al. (12,13), but has been limited by insufficient sample sizes, high costs, and outdated anatomical data and marks. Therefore, these types of studies can no longer meet the needs of increasingly individualized and refined surgery. Additionally, identifying accurate and complete information from conventional two-dimensional (2D) CT images can be challenging, especially in patients with anatomical abnormalities. In contrast, three-dimensional CT bronchial angiography (3D-CTBA) can be used to display the anatomical structure and spatial relationship of pulmonary vessels and bronchi, determine the intersegmental veins and planes, reasonably develop personalized surgical plans, and optimize surgical workflow (9,11,14-16).

Despite its advantages, few studies have robustly assessed 3D reconstruction techniques for the anatomic visualization of RS8, RS9, and RS10 and related surgical procedures of RS9 segmentectomy. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to characterize the vascular and bronchial branching patterns of the RS8, RS9, and RS10 and summarize our experiences in anatomic RS9 segmentectomy. The clinical insights from this study may assist thoracic surgeons in obtaining a greater awareness of the anatomical characteristics of RS9 and increased familiarity with RS9 segmentectomy. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-2024-1231/rc).

Methods

Patients

A retrospective analysis of patients who underwent segmentectomy at Fujian Medical University Union Hospital between May 2020 and May 2022 was conducted, with all patients undergoing preoperative enhanced CT scans and 3D reconstruction. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) a ground-glass opacity-predominant nodule, with a diameter of less than 3 cm and with a consolidation to tumor ratio of less than 50%; and (II) completion of segmentectomy and preoperative enhanced CT scans and 3D reconstruction. Meanwhile, the exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) a prior history of right lung surgery; (II) blurred CT images and 3D reconstruction not clearly showing the bronchial and vascular anatomical structures; and (III) incomplete medical records. Finally, a total of 354 patients meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled, while 11 patients were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. Date security and privacy were ensured throughout the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the review committee of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (No. 2025KY021). The need for written informed consent was waived due to the anonymity of data and the retrospective nature of the analysis.

CT data and 3D reconstruction

CT data were acquired using a 128-channel revolution Light Speed VCT scanner (GE HealthCare, Chicago, IL, USA) with the slice thickness set at 0.625 mm. The imaging data were stored in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format. The CT image DICOM data were imported into the Mimics 21.0 interactive medical image control system (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) to construct a 3D model of the bronchi, pulmonary arteries and pulmonary veins, lung segments, and nodules. By comparing the complete 3D reconstruction images with the 2D CT images, two experienced thoracic surgeons confirmed the correctness of the corresponding bronchial and vascular reconstruction. If there was a discrepancy in their opinions, it was discussed with another chief surgeon to achieve a consistent result. Subsequently, the branching patterns of the bronchi, pulmonary arteries, and veins were recorded, and the frequency of each type was calculated.

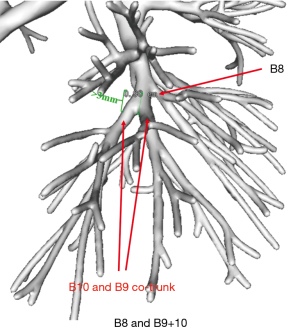

Assessment of the branching pattern

The bifurcation and co-trunk were determined according to the location of the bronchial and vascular emanations at each level. A common trunk of 3 mm or greater was defined as a co-trunk, while a common trunk length less than 3 mm was considered only to be a tendency toward co-trunking and was recorded as a bifurcation (Figure 1). The bronchial and vascular branching patterns of RS8, RS9, and RS10 were classified into bifurcated and trifurcated types according to Nagashima et al.’s study (14). Additionally, the bifurcated types of the arteries or veins were further divided into two subtypes: simple and split. In the simple bifurcation type meant, each basal segment is supplied/drained by a single segmental artery/vein, while in the split type, at least one basal segment is supplied/drained by two segmental arteries/veins.

Operative procedure of RS9 segmentectomy

For RS9 segmentectomy, the patients underwent routine contrast-enhanced high-resolution CT (HRCT) scans and 3D reconstruction before surgery. The surgical team members carefully interpreted HRCT and 3D reconstruction to design the most appropriate surgical plan, including the surgical approach, target vessels and bronchi to be resected, extent of resection, and tailoring steps. Moreover, a resection margin greater than 2 cm or greater than the diameter of the tumor needed was ensured.

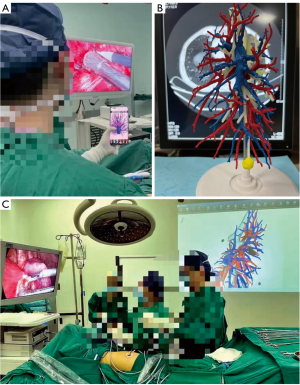

After general anesthesia, RS9 segmentectomy was performed with the assistance of a thoracoscope. A 1.0-cm port, placed in the seventh intercostal space of the midaxillary line, was used for the thoracoscope. A 2- to 3-cm port, placed in the fifth intercostal space of the anterior axillary line, and a 1.5-cm port, placed in the eighth intercostal space of the posterior axillary line, were used as the operating ports. The inferior pulmonary ligament approach was preferred because as compared to the interlobar fissure approach, it can reduce the extensive dissociation of adjacent lung structures and decrease surgical trauma and the frequency of postoperative complications (8-10). However, if the interlobar fissure is well developed, and the structure of RS9 is easy to access through the interlobar fissure, or when the bronchial and vascular branches of S7a and S7b straddle the inferior pulmonary vein (IPV), which affects the exposure of the deep RS9 through the inferior pulmonary ligament approach. In such cases, the interlobar fissure approach may be selected, as it simultaneously allows for better identification of the target artery and bronchus. Besides, when RS9 segmentectomy is difficult to perform using only the interlobar fissure or inferior pulmonary ligament approaches, a combined surgical approach can be considered. Additionally, intraoperative 3D reconstruction of patient anatomy was compared in real-time with aseptically packaged mobile phones, 3D-printed models, or projectors (Figure 2), especially in procedures performed through the inferior pulmonary ligament approach, which demands accurate identification of the target pulmonary veins.

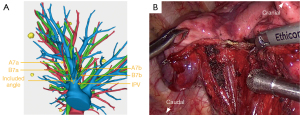

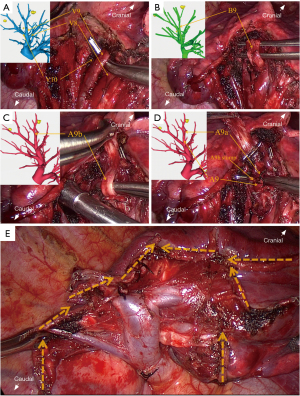

The following is an example description of a procedure performed via the inferior pulmonary ligament approach. First, the right lower pulmonary ligament was incised, and the right lower pulmonary vein was exposed. If a special situation occurred in which the bronchial and vascular branches of S7a and S7b straddle the IPV and form an “included angle” (Figure 3A), the S7 was required to be separated using endoscopic stapler and ultrasonic scalpel (Figure 3B), as this included angle can affect the exposure of the deep RS9 and increase surgical difficulty. According to the preoperative 3D reconstruction plan, the branch of the lower pulmonary vein was fully dissociated to the distal end. After the internal vein of the target segment was ligated, the target vein was excised with an ultrasonic scalpel. The target bronchus was further dissected and severed with the endoscopic stapler. The target artery was then located and dissociated with reference to the route of the bronchus. After ligation, an endoscopic stapler or ultrasonic scalpel was used to sever the artery (Figure 4A-4D). Subsequently, the ISP was identified via the inflation-deflation method. The tailoring process was simulated by referring to the preoperative 3D reconstruction, and then the targeted pulmonary parenchyma was extensively dissected with an ultrasonic scalpel and staplers in a 3D-tailored manner. The staplers were applied to tailor the lung parenchyma for a long span, while the ultrasonic scalpel was used to perform minor cropping and adjustments. RS7 and RS9 were separated from the diaphragmatic surface, and then the ISPs of RS8 and RS9 and of RS9 and RS10 were sequentially divided from the inferior margin. Finally, RS9 was separated from RS6, and the target segment was completely isolated (Figure 4E). Subsequently, the surgical margin was inspected immediately after resection. The specimen was sent for intraoperative frozen section examination as a reference to determine whether further extensive resection, such as systematic mediastinal lymph node dissection or lobectomy, was required. Air leakage was evaluated by inflating the remaining lung under a water seal, and hemostatic materials (e.g., Surgicel) along with biological glue were applied to control air leaks and minimize blood oozing.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for Windows. Continuous variables are expressed as the median and range, and categorical variables as numbers and percentages.

Results

A total of 354 patients were included in the study. All patients underwent enhanced CT scan and 3D reconstruction before surgery, and segmentectomy was successfully completed in all patients. Vascular and bronchial branching patterns of RS8, RS9, and RS10 were analyzed in these patients, 27 of whom underwent anatomical RS9 segmentectomy guided by 3D reconstruction. Although 11 patients had pulmonary nodules located in RS9, 8 patients underwent RS8+9 or RS9+10 segmentectomy due to the long co-trunk of the artery and/or bronchus between RS9 and RS8 or RS10. Additionally, 3 patients required RS8+9 or RS9+10 segmentectomy because the resection margin partially involved RS8 or RS10. In total, there were 9 cases of RS9+10 segmentectomy and 2 cases of RS8+9 segmentectomy.

The branching patterns of B8, B9, and B10

First, the branching patterns of the right basal bronchi (B8, B9, and B10) were assessed. The branching patterns were relatively simple, and the B8 and B9+10 type (74.6%), which was bifurcated, was the most common pattern. Two other types of bronchial branches were noted, the B8+9 and B10 type (also bifurcated) and the B8, B9, and B10 type (trifurcated), which accounted for 15.3% and 10.2% of the cases, respectively (Figure 5 and Table 1).

Table 1

| Type | Subtype | Cases (n) | Proportion (%) | Nagashima et al. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchus | ||||

| Bifurcated | B8 and B9+10 | 264 | 74.60 | 80.40 |

| B8+9 and B10 | 54 | 15.30 | 15.20 | |

| Trifurcated | B8, B9, and B10 | 36 | 10.20 | 4.40 |

| Artery | ||||

| Bifurcated | ||||

| Simple bifurcated | A8 and A9+10 | 221 | 62.40 | 68.10 |

| A8+9 and A10 | 46 | 13.00 | 11.10 | |

| Split bifurcated | A8 and A8+9+10 | 65 | 18.40 | 14.10 |

| A8+9 and A9+10 | 13 | 3.70 | 2.60 | |

| Trifurcated | A8, A9, and A10 | 9 | 2.50 | 4.10 |

| Vein | ||||

| Bifurcated | ||||

| Simple bifurcated | V8 and V9+10 | 41 | 11.60 | 20.40 |

| V8+9 and V10 | 104 | 29.40 | 25.20 | |

| Split bifurcated | V8+9+10 and V10 | 90 | 25.40 | 31.10 |

| V8+9 and V9+10 | 76 | 21.50 | 20.70 | |

| V8 and V8+9+10 | 4 | 1.10 | – | |

| V8+9+10 and V9+10 | 4 | 1.10 | – | |

| Trifurcated | V8, V9, and V10 | 11 | 3.10 | 2.60 |

| V8, V9+10, and V10 | 10 | 2.80 | – | |

| V8+9, V9+10, and V10 | 11 | 3.10 | – | |

| V8+9, V10 and V10 | 3 | 0.80 | – |

RS8, RS9, and RS10, the right anterior, lateral, and posterior basal segments; B8, B9, and B10, bronchi of the right anterior, lateral, and posterior basal segments; A8, A9, and A10, pulmonary arteries of the right anterior, lateral, and posterior basal segments; V8, V9, and V10, pulmonary veins of the right anterior, lateral, and posterior basal segments.

The branching patterns of A8, A9, and A10

The branching patterns of the right basal arteries (A8, A9, and A10) were then assessed. The branching patterns were primarily classified into two types: the bifurcation type, which was predominant (n=345, 97.5%), and the trifurcation type, which was rare (n=9, 2.5%). The bifurcation type was further divided into two subtypes: the simple bifurcated type (i.e., the A8 and A9+10 type and the A8+9 and A10 type) and the split bifurcated type (i.e., the A8 and A8+9+10 type and the A8+9 and A9+10 type). In 221 (62.4%) patients, the basal arteries bifurcated into the A8 and A9+10, which was the most common type. The A8+9 and A10 types were observed in 46 cases (13.0%). The second most common pattern in the basal arteries was the A8 and A8+9+10 types, which were present in 65 patients (18.4%). In contrast, the A8+9 and A9+10 types were observed in only 13 cases (3.7%). As for the trifurcation type (the A8, A9, and A10 types), it was present in only 9 cases (2.5%) (Figure 6 and Table 1).

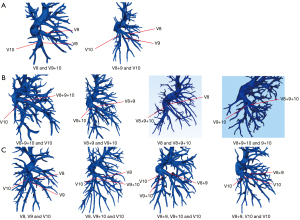

The branching patterns of V8, V9, and V10

Finally, the branching patterns of the right basal veins (V8, V9, and V10) were assessed. These patterns were more complex and were classified into bifurcation and trifurcation types. Bifurcation was evident in 319 cases (90.1%), while trifurcation was the less common. The bifurcation type was also further divided into the simple bifurcated type and the split bifurcated type. The former included the V8 and V9+10 type and the V8+9 and V10 type, accounting for 11.6% and 29.4% of the cases, respectively. The split bifurcated type included the V8+9+10 and V10 type, the V8+9 and V9+10 type, the V8 and V8+9+10 type, and the V8+9+10 and V9+10 type, accounting for 25.4%, 21.5%, 1.1%, and 1.1% of cases, respectively. The trifurcation type was further divided into four subtypes: subtype I (the V8 and V9 and V10 type), which was observed in 11 cases (3.1%); subtype II (the V8 and V9+10 and V10 type), which occurred in 10 cases (2.8%); subtype III (the V8+9 and V9+10 and V10 type); and subtype IV (the V8+9 and V10 and V10 type), which were present in 11 cases (3.1%) and 3 cases (0.8%), respectively (Figure 7 and Table 1).

Surgical outcomes

Of the patients included, 7.6% (27/354) of patients underwent anatomical RS9 segmentectomy. All thoracoscopy procedures were completed without conversion to thoracotomy. The inferior pulmonary ligament approach and interlobar fissure approach were applied in 19 (70.4%) and 6 (22.2%) patients, respectively, while the combined approach was applied in 2 (7.4%) patients. The median operative time was 131 minutes (range, 87–211 minutes), and the median intraoperative blood loss was 37 mL (range, 10–200 mL). Postoperative atelectasis occurred in 2 cases (7.4%), pneumonia in 3 cases (11.1%), hemoptysis in 1 case (3.7%), and prolonged air leakage (>7 days) in 1 case (3.7%), all of which resolved with conservative treatment. The median postoperative drainage time was 5 days (range, 3–11 days), and the median length of postoperative hospital stay was 5 days (range, 3–12 days). The confirmed pathologies of lesions included minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA) in 21 cases (77.8%) and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) in 6 cases (22.2%). The median tumor size was 11 mm (range, 7–24 mm) (Table 2). Overall, these data indicated that thoracoscopic RS9 segmentectomy under the guidance of 3D reconstruction is safe and feasible.

Table 2

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Surgical approach | |

| Inferior pulmonary vein | 19 (70.4) |

| Interlobar fissure | 6 (22.2) |

| Combined | 2 (7.4) |

| Operative time (min) | 131 [87–211] |

| Blood loss (mL) | 37 [10–200] |

| Postoperative complications | |

| Atelectasis | 2 (7.4) |

| Pneumonia | 3 (11.1) |

| Hemoptysis | 1 (3.7) |

| Prolonged air leakage (>7 day) | 1 (3.7) |

| Postoperative drainage time (day) | 5 [3–11] |

| Postoperative hospital stays (day) | 5 [3–12] |

| Pathological results | |

| MIA | 21 (77.8) |

| AIS | 6 (22.2) |

| Tumor size (mm) | 11 [7–24] |

Data are presented as n (%) or median [range]. RS9, the right lateral basal segment; 3D, three-dimensional; MIA, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma; AIS, adenocarcinoma in situ.

Discussion

A complex segmentectomy creates several intricate ISPs and is characterized as a complex procedure. This approach can provide adequate operative outcomes in patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (17,18). However, failure to fully recognize the segmental anatomy leads to a high probability of additional structural damage and extended excision during surgery, making it impossible to perform scheduled surgery. Anatomical RS9 segmentectomy is considered one of the most challenging thoracic surgeries because of its deep hilar structure, intricate ISPs, and frequent variations of segmental vessels and bronchi; thus, preoperative 3D reconstruction is essential. Pulmonary 3D reconstruction images facilitate the comprehensive reconstruction of the lung’s entire structure. They allow for the flexible adjustment of viewing angles and the separation and integration of pulmonary bronchi, arteries, and veins. This approach accurately captures the spatial relationship between the lesion and the target segment structure. The shape is realistic, and the 3D structure is strong, providing an accurate reference for formulating surgical protocols. Previous reports have confirmed that 3D reconstruction can effectively guide thoracoscopic segmentectomy to ensure the safety and radical resection of the lung surgery, especially in complicated segmentectomies (9,11,19,20).

In this study, we analyzed the bronchovascular patterns of the right anterior, lateral, and posterior basal segments (RS8, RS9, and RS10, respectively) and found they were similar to those published by Nagashima et al. (14). Although some cases shared the same branching patterns of the artery and bronchus, their vein branching varied, with a greater number of branching types being found for pulmonary veins. For example, eight cases had the split bifurcated pattern of V8 and V8+9+10 or V8+9+10 and V9+10, which Nagashima et al. did not report in their study. Additionally, their study’s trifurcated pattern of pulmonary veins contained only subtype I (the V8, V9, and V10 types); in contrast, we discovered three additional types, accounting for 6.7% of the cases. Although these types were only found in a relatively small number of cases, once they appear in the surgical region, surgeons may make empirical judgments, leading to mishandling or errors. Thus, these clinical insights should be given due attention. Notably, for S9 or S10 segmentectomies performed through the inferior pulmonary ligament approach, it is imperative to first identify and dissect the venous branches of the corresponding target segment (6,8-10,21-23). A thorough understanding of the anatomical characteristics of the veins is especially crucial in this context.

A total of 27 patients underwent thoracoscopic RS9 segmentectomy under the guidance of 3D reconstruction. Of these procedures, the inferior pulmonary ligament approach was preferred and was performed in 21 cases (77.8%). With the detailed analysis of 3D reconstruction before surgery, we could thoroughly understand the target segmental structure, especially the venous branching patterns. Furthermore, referencing the 3D reconstruction model during surgery allowed for accurate and efficient intraoperative anatomy (such as identifying target vessels and bronchi, intersegmental veins, and adjacent structures), thus guaranteeing surgical safety and efficiency via the inferior pulmonary ligament approach. In cases where the interlobar fissure is well developed, the interlobar fissure approach can be selected, making it easier to identify the target arteries and bronchi. However, RS9 segmentectomy via the interlobar fissure approach requires extensive dissection and separation of adjacent lung tissue (7), which not only increases the difficulty and trauma of the operation but also leads to compression and deformation of the adjacent retained lung tissue, further impairing lung function and increasing postoperative complications such as hemoptysis and air leakage.

It is worth noting that a combined surgical approach may be more sensible when RS9 segmentectomy is challenging to perform only through the interlobar fissure or inferior pulmonary ligament approaches. This implies that the structure of the S9b subsegment can be dissected through the inferior pulmonary ligament approach, and the structure of the S9a subsegment can be dissected through the interlobar fissure approach. Finally, the ISPs can be tailored through the interlobular and inferior pulmonary ligament approaches. This strategy is an ideal method for verifying difficult-to-identify vessels or bronchi (9).

The vascular and bronchial branching patterns of RS7 were not summarized in this study because of RS7’s small volume and relative independence from RS9. However, when the bronchial and vascular branches of S7a and S7b straddle the IPV, the structure of RS7 will be encountered first in RS9 segmentectomy through the inferior pulmonary ligament approach (Figure 3). In this case, RS7 needs to be separated, as this affects the exposure of the deep RS9, and it can be observed more directly by 3D reconstruction than by 2D CT. In other words, the interlobar fissure approach could be prioritized to avoid damage to RS7. We also took subsuperior segment (S*) into account when classifying the anatomical types of the right basal segments, which was present in 87 out of 354 cases (24.6%). The presence of S* should not be ignored, particularly when performing RS9 segmentectomy through an interlobar fissure approach. In this approach, B* may be encountered before the branch of B9, potentially leading to incorrect division of B*. That is to say, the inferior pulmonary ligament approach may offer distinct advantages in this scenario. Moreover, if the bronchus and artery of RS9 share a long common trunk with RS8 or RS10 or if the anatomical structure is too complex to dissect, RS9 segmentectomy alone may increase operative time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative air leakage, hemoptysis, and other complications. Therefore, according to the anatomical characteristics of 3D reconstruction, RS8+9 or RS9+10 segmentectomy (8 cases in this study) may be a more suitable choice for simplifying the surgery and reducing surgical complications. In cases where the lesion in RS9 was located too close to the intersegmental border between RS9 and RS8 or RS10, a combined RS8+9 or RS9+10 segmentectomy was also necessary to ensure a safe resection margin (3 cases in this study).

Anatomical RS9 segmentectomy is challenging due to the intricate ISPs and variation in the anatomical structures involved. The application of 3D reconstruction enables surgeons to conduct detailed preoperative surgical planning and accurate intraoperative navigation. In addition, preoperative 3D reconstruction can help identify which patients can undergo independent complete RS9 segmentectomy and which patients should forego RS9 segmentectomy for more appropriate procedures such as combined segmentectomy or even lobectomy, maximizing the benefit to patients.

It is also worth noting that the economic implication of 3D reconstruction technology is one of the key factors contributing to its widespread application. The application of 3D reconstruction in lung surgery enhances surgical precision, prevents inadvertent injury to critical structures, reduces intraoperative accidents and operating time, and lowers the incidence of complications. As a result, it facilitates faster patient recovery, shortens hospital stays, and optimizes resource utilization, all of which contribute to reducing overall healthcare costs. While 3D reconstruction technology requires a significant initial investment (e.g., equipment, software, and staff training costs), in the long run, it offers substantial cost savings and a higher return on investment by improving surgical efficiency, reducing complications, and lowering hospitalization expenses. Therefore, this technology holds considerable economic value, particularly in the context of complex segmentectomies, where its potential can be fully realized.

This study involved several limitations which should acknowledged. First, 3D reconstruction is based on pulmonary CT images, which may lead to incomplete reconstruction of small bronchi and vessels due to the quality of CT images. Second, the sample size of this study was small, and thus a more extensive and multicenter study is required to confirm the results. Third, to what extent the findings obtained from this study could improve surgical outcomes should be verified in subsequent research.

Conclusions

In this study, we identified 354 cases of pulmonary 3D reconstruction and analyzed the anatomical variations in the bronchovascular patterns of the right basal segments (RS8, RS9, and RS10). Next, thoracoscopic RS9 segmentectomy guided by 3D reconstruction was completed in 27 patients, and the procedure difficulties and surgical experiences were summarized. The clinical insights described in this study can help thoracic surgeons better understand the related anatomical structures and more safely and accurately perform RS9 segmentectomy.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-2024-1231/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-2024-1231/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-2024-1231/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-2024-1231/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the review committee of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (No. 2025KY021). The need for written informed consent was waived by the review committee of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital due to the anonymity of the data and the retrospective nature of the analysis.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med 2020;382:503-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saji H, Okada M, Tsuboi M, et al. Segmentectomy versus lobectomy in small-sized peripheral non-small-cell lung cancer (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2022;399:1607-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Altorki N, Wang X, Kozono D, et al. Lobar or Sublobar Resection for Peripheral Stage IA Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2023;388:489-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Potter AL, Kim J, McCarthy ML, et al. Segmentectomy versus lobectomy in the United States: Outcomes after resection for first primary lung cancer and treatment patterns for second primary lung cancers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2024;167:350-364.e17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hattori A, Suzuki K, Takamochi K, et al. Segmentectomy versus lobectomy in small-sized peripheral non-small-cell lung cancer with radiologically pure-solid appearance in Japan (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L): a post-hoc supplemental analysis of a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2024;12:105-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu C, Liao H, Guo C, et al. Single-direction thoracoscopic basal segmentectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2020;160:1586-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Igai H, Kamiyoshihara M, Kawatani N, et al. Thoracoscopic lateral and posterior basal (S9 + 10) segmentectomy using intersegmental tunnelling. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2017;51:790-1. [PubMed]

- Takamori S, Oizumi H, Suzuki J, et al. Thoracoscopic anatomical individual basilar segmentectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2022;62:ezab509. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang L, Wang T, Feng Y, et al. Clinical application of VATS combined with 3D-CTBA in anatomical basal segmentectomy. Front Oncol 2023;13:1137620. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li G, Luo Q, Wang X, et al. Inferior pulmonary ligament approach and/or interlobar fissure approach for posterior and/or lateral basal segment resection: a case-series of 31 patients. J Thorac Dis 2022;14:4904-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang M, Liu X, Ge M. Prevalence and anatomical characteristics of medial-basal segment in right lung. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2023;64:ezad342. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith FR, Boyden EA. An analysis of variations of the segmental bronchi of the right lower lobe of 50 injected lungs. J Thorac Surg 1949;18:195-215. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferry RM Jr, Boyden EA. Variations in the bronchovascular patterns of the right lower lobe of fifty lungs. J Thorac Surg 1951;22:188-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagashima T, Shimizu K, Ohtaki Y, et al. Analysis of variation in bronchovascular pattern of the right middle and lower lobes of the lung using three-dimensional CT angiography and bronchography. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;65:343-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu S, Xu W, Li Z, et al. Branching patterns and variations of the bronchus and blood vessels in the superior segment of the right lower lobe: a three-dimensional computed tomographic bronchography and angiography study. J Thorac Dis 2023;15:6879-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li Z, Zhao Q, Wu W, et al. Analysis of bronchovascular patterns in the left superior division segment to explore the relationship between the descending bronchus and the artery crossing intersegmental planes. Front Oncol 2023;13:1183227. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Handa Y, Tsutani Y, Mimae T, et al. A Multicenter Study of Complex Segmentectomy Versus Wedge Resection in Clinical Stage 0-IA Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2022;23:393-401. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Handa Y, Tsutani Y, Mimae T, et al. Surgical Outcomes of Complex Versus Simple Segmentectomy for Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;107:1032-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang M, Lv H, Wu T, et al. Application of three-dimensional computed tomography bronchography and angiography in thoracoscopic anatomical segmentectomy of the right upper lobe: A cohort study. Front Surg 2022;9:975552. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamada A, Oizumi H, Kato H, et al. Outcome of thoracoscopic anatomical sublobar resection under 3-dimensional computed tomography simulation. Surg Endosc 2022;36:2312-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kikkawa T, Kanzaki M, Isaka T, et al. Complete thoracoscopic S9 or S10 segmentectomy through a pulmonary ligament approach. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015;149:937-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pu Q, Liu C, Guo C, et al. Stem-Branch: A Novel Method for Tracking the Anatomy During Thoracoscopic S9-10 Segmentectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;108:e333-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu C, Wang W, Mei J, et al. Uniportal Thoracoscopic Single-Direction Basal Subsegmentectomy (Left S10a+ci): Trans-Inferior-Pulmonary-Ligament Approach. Ann Surg Oncol 2022;29:1389-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(English Language Editor: J. Gray)