Comparative outcomes of first-line PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors plus chemotherapy for advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials

Highlight box

Key findings

• Compared to programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors, programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) inhibitors plus chemotherapy possessed the potential to yield superior outcomes in patients with advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

• Among PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, camrelizumab was the optimal first-line option when combined with chemotherapy for patients with advanced squamous NSCLC.

What is known and what is new?

• PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors combined with chemotherapy have been recommended as standard first-line therapeutic options for patients with advanced squamous NSCLC. However, given the absence of evidence from head-to-head comparisons, it remains unclear as to which combination regimen of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and chemotherapy yields the optimal survival benefit.

• This network meta-analysis found that compared to PD-L1 inhibitors, PD-1 inhibitors have the potential to yield superior outcomes when combined with first-line chemotherapy for advanced NSCLC, with camrelizumab appearing to be the optimal first-line option.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• This network meta-analysis provides a reference for clinicians and patients when selecting the optimal first-line chemoimmunotherapy.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy and the leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally, accounting for 12.4% of new cases and 18.7% of deaths in 2022, respectively (1). Nearly 85% of lung cancer cases are non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and the squamous cell carcinoma histological subtype accounts for approximately 25% to 30% of all NSCLC cases (2). In contrast to the more common adenocarcinoma subtype, squamous NSCLC poses therapeutic challenges due to its inherent complexity (e.g., tumor location and high comorbidity burden) and a lower likelihood of driver gene mutations (3-5). Prior to the advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), platinum-doublet chemotherapy had long been the preferred first-line treatment for patients with advanced squamous NSCLC, but the clinical benefits were extremely limited (6,7).

Pembrolizumab was the first ICI developed to target programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) in the systematic treatment of squamous NSCLC irrespective of the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression level and was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to be used in combination with chemotherapy for the first-line treatment of advanced squamous NSCLC in 2018 (8). Subsequently, more phase 3 trials were conducted to evaluate PD-1 inhibitors (such as camrelizumab, tislelizumab, and cemiplimab) or PD-L1 inhibitors (such as atezolizumab and sugemalimab) in combination with chemotherapy as first-line treatment in this population, which showed a substantial improvement in both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) (9-13). Most of these combinations have been approved and recommended as standard first-line therapeutic options, reflecting a shift from cytotoxic therapies to immune-based regimens for advanced squamous NSCLC in this setting. However, despite the dramatic advancements in the treatment of this disease, clinicians often face uncertainty in selecting the optimal combination strategy given the lack of head-to-head comparative studies. Therefore, it is important to conduct a meta-analysis on randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of chemoimmunotherapy to provide indirect comparative data and inform drug selection at the clinical level.

Although several meta-analyses focusing on immunotherapy in overall NSCLC and non-squamous disease have been conducted (14-16), such analysis specifically for squamous NSCLC remains scarce. In this context, we conducted a systematic review and network meta-analysis of RCTs to compare the benefits of different regimens combining PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced squamous NSCLC. The results of this comparison provide available evidence for clinicians to formulate optimal therapeutic strategies for patients scheduled to receive first-line chemoimmunotherapy. We present this article in accordance with the PRISMA NMA reporting checklist (17) (available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-2025-83/rc).

Methods

The protocol of this study was registered in PROSPERO (Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; No. CRD42023427656).

Data sources and search strategies

We systematically searched the PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the ClinicalTrials.gov databases until October 16, 2024, for RCTs on ICIs (including anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1) combined with chemotherapy in NSCLC published in the English language. To avoid omissions and include the most recent data, abstracts from major annual conferences held between 2021 to 2024 were also searched, including those of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), American Association for Cancer Research (AACR), European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), European Lung Cancer Congress (ELCC), and The World Conference on Lung Cancer (WCLC). The detailed searching strategy is listed in the supplementary methods (Appendix 1).

Study selection

Studies were eligible if they enrolled treatment-naïve adult patients with advanced squamous NSCLC, compared PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors combined with chemotherapy with chemotherapy alone in the first-line setting, and were an RCT with reported outcomes of PFS, OS, objective response rate (ORR), or grade 3–5 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs). Articles were excluded if they only included a study protocol; had duplicated results for the identical population data; were non-RCTs, were reviews and letters; or were RCTs on other immunotherapies in addition to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Titles and abstracts were meticulously screened and reviewed to ascertain if the trials fulfilled the inclusion criteria. When long-term follow-up and updated data from the same trial were reported, only the most recent data were included.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Detailed data from the included RCTs were independently extracted into a standard form by two authors (Z.L. and Z.W.) using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Any disagreements during the process of data extraction were resolved via discussion between these two responsible authors until a final consensus was reached. The trial items extracted were as follows: trial name, registered identity (ID) on the ClinicalTrials.gov, first author, publication year, number of enrolled patients, patient characteristics [including age, gender, smoking status, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), and PD-L1 expression], clinical stage, interventions and controls, duration of response (DoR), odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for ORR, hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CI for PFS and OS, and incidence of grade 3–5 TRAEs. Each included trial underwent a rigorous review process conducted by two additional authors (J.Z. and L.H.) to ensure the absence of mislabeling or missing data.

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (version 2.0) was independently applied by two authors (H.T. and Z.H.) to evaluate the quality of the included trials, with any discrepancies being resolved through discussion and input from a third author (Y.H.). The evaluation was based on the following five domains: randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported result (18). The risk-of-bias for each domain was judged to be low-risk, high-risk, or somewhat concerning according to the summary of the evaluation results.

Statistical analysis

Fixed-effect models were used to analyze OS (primary outcome), PFS, ORR, DoR, and the incidence of grade 3–5 TRAEs (secondary outcomes). With chemotherapy as the anchor, effect sizes were compared using HRs with corresponding 95% credible intervals (CrIs) for PFS and OS, with the mean difference and 95% CrIs for DoR, and with ORs with 95% CrIs for ORR and the incidence of grade 3–5 TRAEs.

The network meta-analysis in a Bayesian framework with a Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation method was performed to compare and rank the treatment effects from comparisons of different treatments. A funnel plot was used to assess the publication bias. Additionally, subgroup analyses for both OS and PFS were performed according to the baseline features. All statistical analyses were carried out using R software version 4.1.2 (The R Foundation of Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), specifically “gemtc” package version 1.0-1 and JAGS software (version 4.3.0). For each outcome measure, Markov chains were established by running 10,000 burn-ins and 50,000 sample iterations with 10 step-size iterations with a fixed-effect consistency model, and this method was used to generate model parameters in posterior distributions. Since all comparisons were made in only a single trial, there were no sources of inconsistency in our study. The Bayesian approach also provided overall ranking probabilities for each ICI combination, and each outcome measurement was ranked from the best to the worst by calculating the surface under the cumulative ranking curves.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

A total of 1,411 records were identified by the search strategy, including 797 from databases and 614 from other sources. After initial review, 523 duplicates from databases were removed (Figure 1). Finally, a total of nine RCTs were included for analysis, with 3,210 patients with advanced squamous NSCLC involved, who received a variety of therapeutic regimens including six PD-1 inhibitors (camrelizumab, pembrolizumab, tislelizumab, sintilimab, toripalimab, and cemiplimab) plus chemotherapy, three PD-L1 inhibitors (atezolizumab, durvalumab, and sugemalimab) plus chemotherapy, and chemotherapy alone. Most of the RCTs included were double-blinded trials. The detailed characteristics of each trial included are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Trial name | Study | Registered ID | Phase | Design | Randomization | Sample size | Squamous (%) | Clinical stage | Intervention arm | Control arm (chemotherapy) | Median follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CameL-Sq (9,19) | Ren et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2024 |

NCT03668496 | 3 | Double-blind | 1:1 | 193/196 | 100/100 | IIIB–IV | Camrelizumab 200 mg+ carboplatin AUC 5 + paclitaxel 175 mg/m2, Q3W | Placebo + carboplatin AUC 5 + paclitaxel 175 mg/m2, Q3W | 53.5 (range, 47.5–61.0) months |

| CHOICE-01 (20) | Wang et al., 2023 | NCT03856411 | 3 | Double-blind | 2:1 | 309/156 | 47.6/46.8 | IIIB–IV | Toripalimab 240 mg + nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2 + carboplatin AUC 5, Q3W | Placebo + nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2 + carboplatin AUC 5, Q3W | 19.4 months |

| EMPOWER-Lung 3 (21,22) | Makharadze et al., 2023; Baramidze et al., 2024 | NCT03409614 | 3 | Double-blind | 2:1 | 312/154 | 42.6/43.5 | IIIB–IV | Cemiplimab 350 mg + platinum doublet chemotherapy, Q3W | Placebo + platinum doublet chemotherapy, Q3W | 37.1 months |

| GEMSTONE-302 (13,23) | Zhou et al., 2022 and 2024 |

NCT03789604 | 3 | Double-blind | 2:1 | 320/159 | 40.0/40.0 | IV | Sugemalimab 1200 mg + carboplatin AUC 5+ paclitaxel 175 mg/m2, Q3W | Placebo + carboplatin AUC 5+ paclitaxel 175 mg/m2, Q3W | 43.5 months in intervention arm; 43.0 months in control arm |

| IMpower131 (12) | Jotte et al., 2020 | NCT02367794 | 3 | Open-label | 1:1:1 | 338/343/340 | 100/100 | IV | Atezolizumab 1,200 mg + carboplatin AUC 6 + paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 (arm A) or nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2 (arm B), Q3W | Carboplatin AUC 6 + nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2 | 26.8 months in intervention arm; 24.8 months in control arm |

| KEYNOTE-407 (24) | Novello et al., 2023 | NCT02775435 | 3 | Double-blind | 1:1 | 278/281 | 100/100 | IV | Pembrolizumab 200 mg + carboplatin AUC 6 + paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 or nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2, Q3W | Saline placebo + carboplatin AUC 6 + paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 or nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2, Q3W | 56.9 (range, 49.9–66.2) months |

| ORIENT-12 (25) | Zhou et al., 2021 | NCT03629925 | 3 | Double-blind | 1:1 | 179/178 | 100/100 | IIIB–IV | Sintilimab 200 mg + gemcitabine 1.0 g/m2 + cisplatin 75 mg/m2 or carboplatin AUC 5, Q3W | Placebo + gemcitabine 1.0 g/m2 + cisplatin 75 mg/m2 or carboplatin AUC 5, Q3W | 12.9 (range, 0.5–17.9) months |

| POSEIDON (26,27) | Peters et al. 2023; Garon et al. 2024 | NCT03164616 | 3 | Open-label | 1:1 | 338/337 | 37.9/36.2 | IV | Durvalumab 1,500 mg + platinum doublet chemotherapy, Q3W | Platinum doublet chemotherapy, Q3W | 63.4 months |

| RATIONALE 307 (10) | Wang et al., 2024 | NCT03594747 | 3 | Open-label | 1:1:1 | 120/119/121 | 100/100 | IIIB or IV | Tislelizumab 200 mg + carboplatin AUC 5 + paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 (arm A) or nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2 (arm B), Q3W | Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 + carboplatin AUC 5, Q3W | 16.7 months |

AUC, area under the curve; Q3W, every 3 weeks.

Comparisons of OS, PFS, DoR, and ORR

Among the nine different treatments, eight contributed to the network for the OS outcome, with sintilimab plus chemotherapy being excluded due to immature data. Analysis included nine treatments for PFS, eight for ORR, seven for DoR, and four for grade 3–5 TRAEs. The network plots are shown in Figure S1.

In terms of OS, therapeutic regimens with PD-1 inhibitors plus chemotherapy resulted in superior OS benefit compared to PD-L1 inhibitors combined with chemotherapy (PD-L1: HR 0.70, 95% CrI: 0.62 to 0.79; PD-L1: HR 0.82, 95% CrI: 0.71 to 0.94; Figure 2A). For PD-1 inhibitors, camrelizumab plus chemotherapy provided the best OS benefit when compared with chemotherapy alone (HR 0.56, 95% CrI: 0.44 to 0.71), whereas toripalimab plus chemotherapy had the worst OS benefit, with an HR of 1.09 (95% CrI: 0.76 to 1.56). Regarding PD-L1 inhibitors, sugemalimab provided the best OS over chemotherapy alone (HR 0.61, 95% CrI: 0.43 to 0.86). In contrast, the other PD-L1 inhibitors, durvalumab and atezolizumab, showed only modest OS benefit, with the HRs of 0.82 (95% CrI: 0.63 to 1.06) and 0.88 (95% CrI: 0.73 to 1.06), respectively.

In terms of PFS, the efficacy outcomes of combinations of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors were like those of OS, with camrelizumab plus chemotherapy also yielding the best benefit among all PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor combination treatments (HR 0.32, 95% CrI: 0.25 to 0.42), followed by sugemalimab plus chemotherapy (HR 0.37, 95% CrI: 0.26 to 0.52; Figure 2B). Besides these two agents, PD-1 inhibitors tislelizumab or toripalimab combined with chemotherapy also reduced the risk of disease progression or death by more than 50% (tislelizumab: HR 0.45, 95% CrI: 0.35 to 0.59; toripalimab: HR 0.49, 95% CrI: 0.35 to 0.69). Durvalumab and atezolizumab prolonged PFS compared with chemotherapy (durvalumab: HR 0.68, 95% CrI: 0.52 to 0.89; atezolizumab: HR 0.71, 95% CrI: 0.60 to 0.84); however, both were associated with worse PFS when compared to other treatments including PD-1 inhibitors.

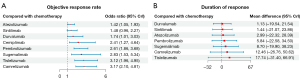

In terms of ORR, camrelizumab remained the superior therapeutic option when combined with chemotherapy (OR 3.17, 95% CrI: 2.10 to 4.81) and was followed by tislelizumab (OR 3.12, 95% CrI: 1.96 to 4.95) and sugemalimab (OR 2.83, 95% CrI: 1.53 to 5.34; Figure 3A). Atezolizumab and sintilimab provided relatively poor benefit in combined therapy and only provided modest improvements in terms of ORR over chemotherapy alone, with ORs of 1.42 (95% CrI: 1.05 to 1.93) and 1.48 (95% CrI: 0.96 to 2.27), respectively.

In terms of DoR, among the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor combinations, tislelizumab plus chemotherapy and camrelizumab plus chemotherapy provided the most pronounced DoR benefits relative to chemotherapy alone, with a mean difference of 17.74 (95% CrI: −31.40 to 66.91) and 12.46 (95% CrI: −26.76 to 50.62), respectively (Figure 3B). The addition of durvalumab and sintilimab to chemotherapy was associated with a shorter DoR, with a mean difference of 1.13 (95% CrI: −19.54 to 21.54) and 1.44 (95% CrI: −21.07 to 23.86).

Safety

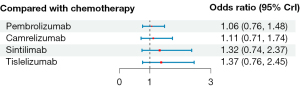

Based on the comparison of overall ORs versus those of chemotherapy alone, the addition of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to chemotherapy was associated with an increase in the risk of developing grade 3–5 TRAEs, as all of the ORs exceeded 1 (Figure 4). Among them, pembrolizumab and camrelizumab had the lowest risk (pembrolizumab: OR 1.06, 95% CrI: 0.76 to 1.48; camrelizumab: OR 1.11, 95% CrI: 0.71 to 1.74), followed by sintilimab (OR 1.32; 95% CrI: 0.74 to 2.37). Tislelizumab was associated with a relatively higher risk of grade 3–5 TRAEs (OR 1.37; 95% CrI: 0.76 to 2.45) than the other three combinations.

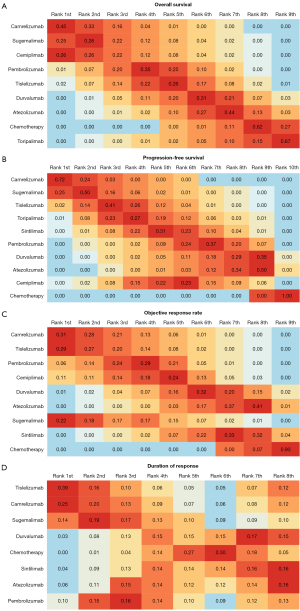

Rank probabilities

Bayesian ranking profiles showed that the ranking results of the OS, PFS, ORR, and DoR were consistent with the findings obtained with the HRs, ORs and mean difference (Figure 5 and Figure S2), further indicating the stability and reliability of the results. For patients with advanced squamous NSCLC, camrelizumab combined with chemotherapy was most likely to rank first for OS (cumulative probability of 45%), PFS (72%), and ORR (31%), while tislelizumab plus chemotherapy was most likely to rank first for DoR (39%; Figure 5).

Subgroup analysis

Given the differences in clinical outcomes among patients with advanced NSCLC with different baseline characteristics, we performed a subgroup analysis to estimate OS and PFS.

For OS, among the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with available subgroup data, camrelizumab showed superior efficacy for PD-L1 expression <1% (HR 0.62, 95% CrI: 0.45 to 0.86) and for PD-L1 expression ≥1% (HR 0.56, 95% CrI: 0.39 to 0.79) as compared to pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, and durvalumab (Figure S3A). Similarly, camrelizumab also showed superiority in both the subgroups of ECOG PS of 0 and 1, with an HR of 0.47 (95% CrI: 0.28 to 0.79) and 0.61 (95% CrI: 0.47 to 0.79), respectively (Figure S3B).

For PFS, sugemalimab and camrelizumab showed the best benefit among the six combinations with available data, both for PD-L1 expression <1% (sugemalimab: HR 0.33, 95% CrI: 0.18 to 0.59; camrelizumab: HR 0.45, 95% CrI: 0.32 to 0.63) and PD-L1 expression ≥1% (sugemalimab: HR 0.33, 95% CrI: 0.22 to 0.50; camrelizumab: HR 0.24, 95% CrI: 0.17 to 0.34) (Figure S4A). In the subgroups of age and ECOG PS, camrelizumab consistently exhibited superior PFS benefit, with HRs of 0.27 (95% CrI: 0.19 to 0.38) for age <65 years, 0.45 (95% CrI: 0.31 to 0.65) for age ≥65 years, 0.35 (95% CrI: 0.20 to 0.61) for an ECOG PS of 0, and 0.32 (95% CrI: 0.25 to 0.41) for an ECOG PS of 1 (Figure S4B,S4C). The most effective agent in combination with chemotherapy among current or former smokers was camrelizumab (HR 0.28, 95% CrI: 0.21 to 0.37), whereas it was tislelizumab among nonsmokers (HR 0.32, 95% CrI: 0.19 to 0.57) (Figure S4D). In addition, tislelizumab yielded a better PFS benefit in both patients with liver metastases (HR 0.51, 95% CrI: 0.27 to 0.96) and those without liver metastases (HR 0.44, 95% CrI: 0.35 to 0.56) than did sintilimab or atezolizumab (Figure S4E).

Risk of bias

The results of the risk of bias assessment conducted with the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool are shown in Figure S5. Overall, most of the trials included in this meta-analysis were at low risk for bias. Additionally, no obvious publication bias was observed in the outcomes, as indicated by the results of the funnel plot (Figure S6).

Discussion

Since PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors combined with chemotherapy replaced chemotherapy alone as the first-line standard treatment for advanced NSCLC in 2016, a growing number of systematic reviews and network meta-analyses have focused on first-line immunotherapies for advanced NSCLC (14,28,29). However, for different histological subtypes, subgroup analysis has been the predominant methodology. This network meta-analysis directly examined advanced squamous NSCLC. It compared the outcomes of various PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors combined with chemotherapy as first-line therapy for this disease. The aim was to provide valuable insights for clinical management decisions.

In this network meta-analysis of nine phase 3 RCTs involving 3,210 patients with advanced squamous NSCLC, we found that the combination of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with chemotherapy conferred superior benefit over chemotherapy alone, with PD-1 inhibitors outperforming PD-L1 inhibitors, which is consistent with previous studies (14,30,31). This discrepancy may be attributed to inherent differences between PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, as PD-1 inhibitors not only bind to PD-1 but also impede its interaction with both PD-L1 and PD-L2. Conversely, PD-L1 inhibitors merely inhibit the binding of PD-1 to PD-L1 without interfering with its interaction with PD-L2, potentially enabling tumors to evade antitumor immune responses through the potential “escape route” mediated by the PD-1-PD-L2 axis (32-34).

Our analysis may also contribute to identifying the optimal PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor for the first-line treatment of advanced squamous NSCLC in clinical settings. With the exception of sintilimab, which was excluded from OS analysis due to insufficient data, the comparative results of the eight PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors plus chemotherapy showed that compared to chemotherapy alone, camrelizumab combined with chemotherapy provide the best outcomes in terms of OS, PFS, ORR, and DoR. Another systematic review and network meta-analysis by Zhao et al., which also focused on squamous NSCLC, reported that sugemalimab provided the most long-term survival benefit (35). This difference may be because we used data from a longer follow-up period and employed different statistical methods. In addition, we compared the outcomes of ORR and DoR. Notably, compared to patients treated with chemotherapy alone, those receiving toripalimab plus chemotherapy demonstrated an improvement in PFS (HR 0.49, 95% CrI: 0.35 to 0.69) but no benefit in OS (HR 1.09, 95% CrI: 0.76 to 1.56), which serves as the optimal endpoint for assessing patient benefit (36).

With respect to safety, the addition of PD-1 inhibitors to chemotherapy resulted in an increased incidence of grade 3–5 TRAEs, and patients treated with camrelizumab or pembrolizumab had the lowest risk of experiencing grade 3–5 TRAEs, suggesting their relatively superior safety profile among all the four regimens with available safety data. Unfortunately, the comparisons of PD-L1 inhibitors could not be performed due to the lack of safety data in squamous disease.

This study involved several limitations which should be addressed. First, the median follow-up time for half of the included studies was less than 3 years, with continued follow-up for OS, and five studies only enrolled Chinese patients, which might have introduced heterogeneity and bias. Second, as not all included studies exclusively focused on squamous NSCLC (such as the POSEIDON, CHOICE-01, EMPOWER-Lung 3, and GEMSTONE-302 trials), it was difficult to obtain complete baseline data, resulting in a failure to obtain the sources of heterogeneity through subgroup analyses.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that PD-1 inhibitors may potentially yield superior outcomes as compared to PD-L1 inhibitors in first-line chemoimmunotherapy regimens for advanced squamous NSCLC. Furthermore, when combined with chemotherapy, camrelizumab appeared to be the most favorable first-line ICI. These findings may serve as a reference for clinicians and patients in the selecting the optimal first-line chemoimmunotherapy; however, differences in follow-up durations, patient populations, and approvals of agents in different regions should be taken into account. Long-term follow-up data and well-designed head-to-head trials are needed to validate our findings.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA NMA reporting checklist. Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-2025-83/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-2025-83/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-2025-83/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bizuayehu HM, Ahmed KY, Kibret GD, et al. Global Disparities of Cancer and Its Projected Burden in 2050. JAMA Netw Open 2024;7:e2443198. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duma N, Santana-Davila R, Molina JR. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Epidemiology, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94:1623-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Socinski MA, Obasaju C, Gandara D, et al. Clinicopathologic Features of Advanced Squamous NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1411-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao W, Choi YL, Song JY, et al. ALK, ROS1 and RET rearrangements in lung squamous cell carcinoma are very rare. Lung Cancer 2016;94:22-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zacharias M, Konjic S, Kratochwill N, et al. Expanding Broad Molecular Reflex Testing in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer to Squamous Histology. Cancers (Basel) 2024;16:903. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3543-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gandara DR, Hammerman PS, Sos ML, et al. Squamous cell lung cancer: from tumor genomics to cancer therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:2236-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paz-Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy for Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2040-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ren S, Chen J, Xu X, et al. Camrelizumab Plus Carboplatin and Paclitaxel as First-Line Treatment for Advanced Squamous NSCLC (CameL-Sq): A Phase 3 Trial. J Thorac Oncol 2022;17:544-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Lu S, Yu X, et al. Tislelizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for advanced squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: final analysis of the randomized, phase III RATIONALE-307 trial. ESMO Open 2024;9:103727. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gogishvili M, Melkadze T, Makharadze T, et al. Cemiplimab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized, controlled, double-blind phase 3 trial. Nat Med 2022;28:2374-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jotte R, Cappuzzo F, Vynnychenko I, et al. Atezolizumab in Combination With Carboplatin and Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced Squamous NSCLC (IMpower131): Results From a Randomized Phase III Trial. J Thorac Oncol 2020;15:1351-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou C, Wang Z, Sun M, et al. 1318P - Four-year outcomes from GEMSTONE-302 study: First-line sugemalimab plus platinum-based chemotherapy in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Ann Oncol 2024;35:S839.

- Liu L, Bai H, Wang C, et al. Efficacy and Safety of First-Line Immunotherapy Combinations for Advanced NSCLC: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J Thorac Oncol 2021;16:1099-117. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tian W, Niu L, Shi Y, et al. First-line treatments for advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer with immune checkpoint inhibitors plus chemotherapy: a systematic review, network meta-analysis, and cost-effectiveness analysis. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2024;16:17588359241255613. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chu X, Tian W, Ning J, et al. Efficacy and safety of personalized optimal PD-(L)1 combinations in advanced NSCLC: a network meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2024;116:1571-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:777-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou C, Ren S, Chen J, et al. 62P First-line (1L) camrelizumab plus chemotherapy (chemo) for advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer (sqNSCLC): 4-yr update from the phase III CameL-sq trial. ESMO Open 2024;9:102641.

- Wang J, Wang Z, Wu L, et al. Final overall survival and biomarker analyses of CHOICE-01: A double-blind randomized phase 3 study of toripalimab versus placebo in combination chemotherapy for advanced NSCLC without EGFR/ALK mutations. J Clin Oncol 2023;41:9003.

- Makharadze T, Gogishvili M, Melkadze T, et al. 1438P Cemiplimab for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Squamous subgroup analysis for EMPOWER-Lung 1 and 3. Ann Oncol 2023;34:S818.

- Baramidze A, Makharadze T, Gogishvili M, et al. Cemiplimab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in non-small cell lung cancer with PD-L1 ≥ 1%: A subgroup analysis from the EMPOWER-Lung 3 part 2 trial. Lung Cancer 2024;193:107821. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou C, Wang Z, Sun Y, et al. Sugemalimab versus placebo, in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy, as first-line treatment of metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (GEMSTONE-302): interim and final analyses of a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet Oncol 2022;23:220-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Novello S, Kowalski DM, Luft A, et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy in Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Update of the Phase III KEYNOTE-407 Study. J Clin Oncol 2023;41:1999-2006. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou C, Wu L, Fan Y, et al. Sintilimab Plus Platinum and Gemcitabine as First-Line Treatment for Advanced or Metastatic Squamous NSCLC: Results From a Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase 3 Trial (ORIENT-12). J Thorac Oncol 2021;16:1501-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peters S, Cho BC, Luft A, et al. LBA3 Durvalumab (D) ± tremelimumab (T) + chemotherapy (CT) in first-line (1L) metastatic NSCLC (mNSCLC): 5-year (y) overall survival (OS) update from the POSEIDON study. Immuno-Oncology and Technology 2023;20:100693.

- Garon EB, Cho BC, Luft A, et al. A Brief Report of Durvalumab With or Without Tremelimumab in Combination With Chemotherapy as First-Line Therapy for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Outcomes by Tumor PD-L1 Expression in the Phase 3 POSEIDON Study. Clin Lung Cancer 2024;25:266-273.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Langer CJ, Gadgeel SM, Borghaei H, et al. Carboplatin and pemetrexed with or without pembrolizumab for advanced, non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, phase 2 cohort of the open-label KEYNOTE-021 study. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1497-508. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ponvilawan B, Sharma P, Mahadevia H, et al. Outcomes of Immunotherapy Versus Chemotherapy as First-Line Treatment in Advanced NSCLC: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. J Thorac Oncol 2023;18:e90-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duan J, Cui L, Zhao X, et al. Use of Immunotherapy With Programmed Cell Death 1 vs Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Inhibitors in Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:375-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kang J, Zhang J, Tian Z, et al. The efficacy and safety of immune-checkpoint inhibitors plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2024;19:e0276318. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohaegbulam KC, Assal A, Lazar-Molnar E, et al. Human cancer immunotherapy with antibodies to the PD-1 and PD-L1 pathway. Trends Mol Med 2015;21:24-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen L, Han X. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy of human cancer: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest 2015;125:3384-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yearley JH, Gibson C, Yu N, et al. PD-L2 Expression in Human Tumors: Relevance to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:3158-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao M, Shao T, Ren Y, et al. Identifying optimal PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in first-line treatment of patients with advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer in China: Updated systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol 2022;13:910656. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tannock IF, Pond GR, Booth CM. Biased Evaluation in Cancer Drug Trials-How Use of Progression-Free Survival as the Primary End Point Can Mislead. JAMA Oncol 2022;8:679-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]