Partial response to lorlatinib in thoracic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor harboring complex and rare ALK fusions: a case report

Highlight box

Key findings

• Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-rearranged inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) responded well to third-generation ALK-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and the initially reported ALMS1-ALK and PLB1-ALK may be sensitive to ALK-TKIs.

What is known and what is new?

• IMT is a rare mesenchymal tumor, with over 50% of cases featuring ALK rearrangements, and first- and second-generation ALK-TKIs have been proven effective for ALK-rearranged IMT.

• In this case report, we present the first-ever patient with advanced IMT harboring ALK rearrangements who was treated with the third-generation ALK-TKI (lorlatinib), resulting in partial response. Furthermore, we have also discovered two novel rare ALK rearrangements that may be sensitive to ALK-TKIs.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Third-generation ALK-TKIs may represent an optimal precision treatment strategy for ALK-rearranged IMT.

• The widespread adoption of genetic testing, especially next-generation sequencing, in mesenchymal tumors is highly necessary.

Introduction

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a rare mesenchymal tumor, with a global incidence rate ranging from 0.04% and 0.70% (1). This entity can manifest in any anatomical site but is more frequently encountered within the lungs or abdominal soft tissues of children and young adults. The histological spectrum of IMT is broad, encompassing spindle cell proliferation in a background of hyalinization and chronic inflammation, to highly cellular myofibroblastic proliferation, with a minority of cases exhibiting distinct atypical tumor components (2). Despite being categorized as a tumor with intermediate biological potential due to its relatively low risk of recurrence and metastasis, IMT is typically treated surgically because of its resistance to conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy, suggesting that treatment options for advanced cases are quite limited (3,4).

The fusion of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene is a hallmark molecular feature of IMTs, with over 50% of IMT cases featuring rearrangements at the ALK locus on chromosome 2p23 (5). ALK rearrangements are indeed associated with ALK expression. ALK fusion proteins activate downstream signaling pathways through ligand-independent autophosphorylation, leading to prolonged survival of tumor cells, increased proliferation, and enhanced cell migration capabilities (6). As a result, ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) represent a potential therapeutic strategy for IMTs.

Lorlatinib is a targeted small molecule TKI that inhibits both ALK and ROS1 (ROS proto-oncogene 1, receptor tyrosine kinase). As the third generation of ALK-TKIs, it exhibits superior resistance to drug resistance, a more potent ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier, and a broader range of binding site capabilities compared to its predecessors (7). It has shown increased clinical efficacy in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with ALK rearrangements and has been approved for the treatment of patients with advanced-stage NSCLC with ALK fusions (8,9).

With the advancement of related research, ALK-TKIs are gradually reshaping the current treatment landscape for ALK-positive IMTs. We present the first case globally of an IMT patient with an EML4-ALK fusion and two rare ALK rearrangements (PLB1-ALK and ALMS1-ALK) who achieved a partial response (PR) following treatment with lorlatinib. We present this case in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-963/rc).

Case presentation

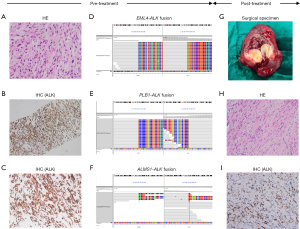

A 48-year-old female with a non-smoking history presented with a persistent dry cough, prompting a medical evaluation. Chest computed tomography (CT) disclosed an extensive mass within the right pleural cavity, interlobar regions, and mediastinum. Further characterization using positron emission tomography (PET)/CT delineated a 108 mm × 128 mm solid neoplasm adjacent to the diaphragmatic aspect of the right pleura, coincident with pronounced lymphadenopathy of stations 2R, 4R, 7, and 10R. Bilateral pulmonary fields exhibited multiple solid nodules and ground-glass opacities (GGOs), with heterogeneously elevated metabolic activity noted across these lesions. A transthoracic needle biopsy of the lung mass confirmed the histopathological diagnosis of an IMT (Figure 1A-1C), staged as T4N2bM1a, corresponding with stage 4A per the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) classification. Advanced molecular profiling via next-generation sequencing (NGS) used OncoScreenPlusTM [Burning Rock, Guangzhou, China; panel covering 520 human cancer-related genes; ALK gene sequencing in this panel covers all exon regions (exons 1–29), as well as introns 18–19 and 21] (table available at https://cdn.amegroups.cn/static/public/tlcr-24-963-1.xlsx) by tumor tissue uncovered the presence of three distinct ALK gene fusions: EML4-ALK, PLB1-ALK, and ALMS1-ALK (Figure 1D-1F). Subsequently, the patient started lorlatinib (100 mg orally once a day) as primary systemic therapy. Three months post-initiation, an updated thoracic CT scan, revealed a marked reduction in the size of the primary thoracic tumor to 55 mm × 39 mm. Concurrently, there was a significant reduction in the size of the involved lymph nodes. Utilizing the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 as the standard for assessment, the radiographic changes were unequivocally classified as PR. The patient continued lorlatinib, and subsequent imaging surveillance at the third and sixth months suggested maintaining the PR status. By 15 months post-initiation, a PET/CT scan revealed a further diminution of the right pleural mass to 29 mm × 24 mm, with significant amelioration of the lymphadenopathy and pulmonary nodules, alongside a pronounced reduction in metabolic activity, reaffirming the PR designation (−75.6%). Given the profound clinical response to lorlatinib and the prospect of curative intent, a right middle lobectomy with systematic lymph node dissection was performed via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. The procedure encompassed an R0 resection of the primary pulmonary lesion, meticulous dissection of the 2R, 4R, 7, and 10R lymph nodes, and extirpation of suspect metastatic nodules within the pericardial mediastinum. Postoperative histopathological examination of the excised specimens was devoid of any residual neoplastic cells. However, subsequent immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis paradoxically disclosed a 15% residual tumor burden within the primary right lung lesion’s resection bed (Figure 1G-1I). In light of the ambiguous nature of the pulmonary nodules’ pathology and the postoperative evidence of residual disease, the patient was initiated on adjuvant therapy with lorlatinib (100 mg orally once a day) 2 weeks post-surgery. Subsequently, the patient underwent regular CT scans every 3 months, with the most recent postoperative imaging from 6 months after surgery, showing no change from prior and no evidence of progression. Until the submission of this manuscript, the patient continues to receive lorlatinib (Figure 2). Notably, during the administration of lorlatinib, the patient experienced grade 3 liver function abnormalities and grade 3 hyperlipidemia, both preoperatively and during the adjuvant therapy phase. Symptomatically, the patient developed paresthesia in the extremities and weight gain. These are common side effects of lorlatinib. After treatment with hepatoprotective and lipid-lowering medications (e.g., evolocumab, rosuvastatin), these abnormal indicators were all controlled to Grade 1 (table available at https://cdn.amegroups.cn/static/public/tlcr-24-963-2.xlsx), and the symptoms were also alleviated. Additionally, due to the stable control of adverse events and the good clinical benefits, we did not adjust the dosage and administration of lorlatinib throughout the patient’s treatment process.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (No. KY2024-071-01). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

This case involves advanced pulmonary IMT with complex ALK fusions. Pulmonary IMT may be asymptomatic or present with symptoms such as cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, and pleurisy pain. Some patients may also experience systemic symptoms like fever, weight loss, and fatigue (10). Radiographically, pulmonary IMT manifests as a solitary, lobulated lesion, predominantly occurring in the peripheral lung parenchyma and subpleural locations, with a predilection for the lower lobes. Pleural effusion may occasionally be present (11). In the case we are reporting, the patient presented with a chronic dry cough. Subsequent PET/CT revealed a large, lobulated mass in the right hemithorax, accompanied by ipsilateral pleural nodules and pleural effusion, with additional solitary nodules visible in both lungs. The clinical presentation is consistent with the known manifestations of IMTs.

Antonescu et al. (12) have identified significant molecular heterogeneity in ALK and a similar function of most ALK gene partners in providing strong promoters and oligomerization domains, which may drive the abnormal activation of the same kinase signals across different tumor types, leading to oncogenesis. In our case, NGS revealed the concurrent presence of EML4-ALK (E6:A20, mutation abundance: 43.89%), PLB1-ALK (P6:A20, mutation abundance: 36.71%), and ALMS1-ALK (A9:A19, mutation abundance: 30.78%) rearrangements. Upon querying the internal genetic databases of Gene Plus and Burning Rock Biotech, the incidence rate of PLB1-ALK ranged from 0.006–0.21%, and that of ALMS1-ALK was 0.002–0.05%. To our knowledge, this is the first report to reveal the existence of ALMS1-ALK fusion and also the first to identify PLB1-ALK fusion in IMT. It is also the first report of the simultaneous occurrence of three types of ALK fusions, two of which are rare. For EML4-ALK, extensive research has already demonstrated its association with the development of various tumors, including IMT. Simultaneously, IMT with EML4-ALK fusion have long been confirmed to be sensitive to ALK-TKIs (13). In contrast, PLB1-ALK has been less reported, initially identified by NGS in lung adenocarcinoma, and later confirmed in a case of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung to have oncogenic driving force and sensitivity to crizotinib (14,15). Although the current evidence is limited, we hyposize that it has an inseparable relationship with the oncogenesis of IMT, and IMT with this fusion may also be sensitive to ALK-TKIs. As for ALMS1-ALK, no related reports have been seen to date. Current knowledge of ALMS1 mutations is limited to its basis in Alström syndrome (AS), a progressive disease characterized by neurosensory and metabolic defects, and its specific biological function remains unknown (16). Research on ALMS1-ALK is a blank slate, with no information available regarding its impact on tumorigenesis or its sensitivity to ALK-TKIs. It is noteworthy that NGS analysis in this case suggests that all three types of ALK fusions retain the kinase domain at the 3' end of ALK, which implies that they likely maintain robust biological functions and are functionally similar. This theory is consistent with existing clinical evidence for EML4-ALK and PLB1-ALK, and it also seems to suggest the possibility that ALMS1-ALK possesses biological functionality. Regrettably, based on the current evidence, we cannot affirm that ALMS1-ALK possesses biological functionality. Moreover, given its association with two types of ALK fusions that have been clearly linked to tumorigenesis and sensitivity to ALK-TKIs, the impact of ALMS1-ALK on the development of IMT and other tumors, as well as its sensitivity to ALK-TKIs, still warrants further exploration. Notably, we have given particular attention to the origin and destination of the three types of fusions. We observed that while their mutational abundances are strikingly similar, the sum of the mutational abundances of the three exceeds 100%. If the three types of fusions were to originate from different clones, it would imply an exceptionally high tumor purity in the patient, a scenario that is very rare. Therefore, this result strongly supports the notion that the three types of fusions originate from a monoclonal rather than a polyclonal source. However, the exact situation still awaits confirmation by methods such as single-cell sequencing. Additionally, the phenomenon of DNA fusion is quite complex; each gene’s breakage and recombination could potentially occur again at unknown genomic locations. Taking the three types of fusions in this case as an example, PLB1-ALK (P6:A20) and ALMS1-ALK (A9:A19) might also accompany the main fusion EML4-ALK (E6:A20) during the process. Nevertheless, rearrangements seen through DNA-targeted sequencing often represent local regions and require additional RNA-level fusion detection to determine their transcript forms and further explore their impact on protein expression. Overall, the discovery of three types of ALK fusions, particularly the novel identification of PLB1-ALK and ALMS1-ALK in IMT, has broadened our understanding of the genetic landscape of IMT. The limited knowledge we have about them has, in turn, spurred the exploration and investigation of their roles in IMT.

Given the variable phenotypes and lack of distinctive IHC characteristics, the diagnosis of IMT has long been one of exclusion. Additionally, the clinical predisposition to mesenchymal tumors often leads to direct treatment without genetic testing. However, the increasing success of targeted therapies in IMTs underscores the importance of genetic testing for these tumors. It is noteworthy that NGS plays an essential role in identifying the driver gene spectrum of IMTs, particularly for ALK. In contrast to the earlier methods of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), IHC, and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), NGS can more precisely distinguish between various subtypes of driver genes, making targeted therapy for different subtypes of driver genes a possibility. Therefore, we strongly advocate for the widespread adoption of NGS in the diagnosis of IMT. Furthermore, for other sarcomas with unclear diagnoses, we also support further research to explore the role of NGS in their characterization.

The utilization of ALK-TKIs to impede the ALK-associated signaling pathways indispensable for the sustained proliferation of IMT has markedly transformed the therapeutic landscape for this disease. In 2010, the first cases of patients treated with crizotinib (a first-generation ALK-TKI) were reported, indicating that IMTs with ALK fusions are responsive to this treatment (17). A subsequent phase II basket trial (EORTC 90101 CREATE) investigated the efficacy of crizotinib in IMTs with or without ALK fusions, with results showing a 50% objective response rate in patients with ALK fusions. Long-term survival outcomes reported a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 18.0 months [95% confidence interval (CI): 4.0–not estimable (NE)] for those with ALK fusions and 14.3 months (95% CI: 1.2–31.1) for those without, with 3-year overall survival rates of 83.3% (95% CI: 48.2–95.6%) and 34.3% (95% CI: 4.8–68.5%), respectively. This further supports the feasibility of crizotinib as a standard treatment for unresectable or metastatic IMTs with ALK fusions (18,19). Second- and third-generation ALK-TKIs, which exhibit higher selectivity for ALK, have demonstrated superior efficacy in advanced NSCLC with ALK fusions (8,20). An increasing number of case reports suggest therapeutic activity of second-generation TKIs in IMTs with ALK fusions. Interestingly, activity has also been observed in crizotinib-resistant IMTs, suggesting the potential to manage IMTs like the management of ALK fusion-positive NSCLC (21,22). Concurrently, a clinical trial assessing brigatinib (a second-generation ALK-TKI) in pediatric IMT patients is underway (NCT04925609) (23). The initially reported ALMS1-ALK and PLB1-ALK may be sensitive to ALK-TKIs, but the presence of EML4-ALK in this case makes this possibility still to be explored.

Conclusions

We report the inaugural case of a third-generation ALK-TKI achieving therapeutic success in advanced IMT with complex ALK rearrangements, including rare and previously uncharacterized fusion subtypes. This case underscores the dependency of ALK-rearranged IMT on ALK-mediated signaling, suggesting that third-generation ALK-TKIs may offer an optimal targeted therapeutic strategy for ALK-dependent mesenchymal tumor subtypes. Furthermore, we encourage larger clinical trials to elucidate further the potential benefits of third-generation ALK-TKIs for ALK-rearranged IMT and more research into the synergistic mechanisms of PLB1-ALK and ALMS1-ALK fusions in TKI therapy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere thanks to the patient and her family for giving their consent to the publication of this case.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-963/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-963/prf

Funding: This work was supported by grants from

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-24-963/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (No. KY2024-071-01). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Panagiotopoulos N, Patrini D, Gvinianidze L, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour of the lung: a reactive lesion or a true neoplasm? J Thorac Dis 2015;7:908-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, et al. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor). A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:859-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology 2014;46:95-104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baldi GG, Brahmi M, Lo Vullo S, et al. The Activity of Chemotherapy in Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumors: A Multicenter, European Retrospective Case Series Analysis. Oncologist 2020;25:e1777-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gleason BC, Hornick JL. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours: where are we now? J Clin Pathol 2008;61:428-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lovly CM, Gupta A, Lipson D, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors harbor multiple potentially actionable kinase fusions. Cancer Discov 2014;4:889-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Basit S, Ashraf Z, Lee K, et al. First macrocyclic 3(rd)-generation ALK inhibitor for treatment of ALK/ROS1 cancer: Clinical and designing strategy update of lorlatinib. Eur J Med Chem 2017;134:348-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaw AT, Bauer TM, de Marinis F, et al. First-Line Lorlatinib or Crizotinib in Advanced ALK-Positive Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2018-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Syed YY. Lorlatinib: First Global Approval. Drugs 2019;79:93-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim JH, Cho JH, Park MS, et al. Pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumor--a report of 28 cases. Korean J Intern Med 2002;17:252-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agrons GA, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Kirejczyk WM, et al. Pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumor: radiologic features. Radiology 1998;206:511-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Antonescu CR, Suurmeijer AJ, Zhang L, et al. Molecular characterization of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors with frequent ALK and ROS1 gene fusions and rare novel RET rearrangement. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:957-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Madueno F, Gould E, Valor R, et al. EML4-ALK Rearrangement and Its Therapeutic Implications in Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumors. Oncologist 2018;23:1127-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang B, Chen R, Wang C, et al. PLB1-ALK: A novel head-to-head fusion gene identified by next-generation sequencing in a lung adenocarcinoma patient. Lung Cancer 2021;153:176-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang S, Wu X, Zhao J, et al. Next-Generation Sequencing Identified a Novel Crizotinib-Sensitive PLB1-ALK Rearrangement in Lung Large-Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma. Clin Lung Cancer 2021;22:e366-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Collin GB, Marshall JD, Ikeda A, et al. Mutations in ALMS1 cause obesity, type 2 diabetes and neurosensory degeneration in Alström syndrome. Nat Genet 2002;31:74-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Butrynski JE, D'Adamo DR, Hornick JL, et al. Crizotinib in ALK-rearranged inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1727-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schöffski P, Sufliarsky J, Gelderblom H, et al. Crizotinib in patients with advanced, inoperable inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours with and without anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene alterations (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer 90101 CREATE): a multicentre, single-drug, prospective, non-randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2018;6:431-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schöffski P, Kubickova M, Wozniak A, et al. Long-term efficacy update of crizotinib in patients with advanced, inoperable inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour from EORTC trial 90101 CREATE. Eur J Cancer 2021;156:12-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, et al. Alectinib versus Crizotinib in Untreated ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:829-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mansfield AS, Murphy SJ, Harris FR, et al. Chromoplectic TPM3-ALK rearrangement in a patient with inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor who responded to ceritinib after progression on crizotinib. Ann Oncol 2016;27:2111-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Z, Geng Y, Yuan LY, et al. Durable Clinical Response to ALK Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Epithelioid Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Sarcoma Harboring PRRC2B-ALK Rearrangement: A Case Report. Front Oncol 2022;12:761558. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rigaud C, Schellekens K, Damm-Welk C, et al. Brigatinib monotherapy in children with R/R ALK+ ALCL, IMT, or other solid tumors: Results from the BrigaPED (ITCC-098) phase 1 study. J Clin Oncol 2024;42:10017.